Mammals

Here’s a section all about the animals that are most like you—that’s right, mammals. Let us tell you a little about yourself and other mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have mammary glands and a four-chambered heart. They give birth to live young (as opposed to laying eggs) and are either partially or completely covered in hair. The teeth of most mammals come in a variety of shapes and sizes designed for chewing many kinds of foods. (Humans, for example, have incisors for cutting, molars for crushing, etc.) Plus, mammals have larger brains than other vertebrates of equal size, making them most capable learners. Which is why you were able to read that last fascinating fact. There’s much more to know about mammals, so spend some time in this section acquainting yourself with these animals.

-

Megan Lorenz

Arctic Fox

Arctic fox (30 s) Arctic fox (5 m) Arctic fox (15 s) Arctic fox (youth)

Megan Lorenz

Arctic Fox

Arctic fox (30 s) Arctic fox (5 m) Arctic fox (15 s) Arctic fox (youth)

The arctic fox Alopex lagopus, or white fox as it is often called, is a member of the canid family and is related to other foxes, wolves, and dogs.It weighs from 2.5 to 9 kg and measures between 75 and 115 cm in length, making it the smallest wild canid in Canada—about the size of a large domestic cat. The long, bushy tail makes up between 30 and 35 percent of its total length.

Over the winter, the arctic fox has a heavy white coat, but during May, when the snow begins to melt, this coat is shed for a thinner, two-tone brown one. Within a few weeks the back, tail, and legs are dark brown and the remaining underparts are a buff colour. A small proportion of arctic foxes have a heavy, pale bluish-grey coat in winter, which becomes thinner and darker bluish-grey in summer. The blue coloration (blue fox) occurs in almost all populations, although the proportion tends to be higher in those animals living in marine areas that remain mostly ice-free during winter. In Canada, blue foxes seldom make up more than 5 percent of animals that are trapped, whereas in Greenland, for example, the proportion of blue foxes may reach 50 percent.

Signs and sounds

The voice of the arctic fox is a sound rarely heard except during the breeding season. Courting foxes communicate with a barking yowl that may be heard over a great distance. Adults also yelp to warn their whelps, or pups, of danger and give a high-pitched undulating whine when disputing territorial claims with neighbouring foxes. -

Thinkstock

Atlantic walrus

Thinkstock

Atlantic walrus

The immense Atlantic walrus is most easily identified by its long tusks and accompanying front and hind flippers. Males have longer and bigger tusks than females. Their dark brown skin is covered by a thin, sparse layer of brown hairs. At birth, the hair is silver grey but quickly turns brown. Male walruses have especially large, muscular-looking necks, with very, thick skin.

A newborn walrus measures about 1.2 metres and weighs approximately 55 kilograms. By adulthood, males measure about 3.1 metres and can weigh about 900 kilograms. Females tend to be smaller, averaging 2.6 metres in length and 560 kilograms in weight.

Unique characteristicsGregarious and intelligent, the Atlantic walrus usually rests in large herds. Although clumsy and slow-moving on land, upon entering the water, the walrus transforms itself into a smooth and graceful swimmer. The Atlantic walrus is a pinniped – literally meaning feather footed – and supports its massive weight on feather-like flippers, in order to navigate its surroundings. Males are much larger than females; an adult male may weight up to one-and-a-half tonnes!

-

Brock Fenton

Bats

Bats (30 seconds) Bats (60 seconds)

Brock Fenton

Bats

Bats (30 seconds) Bats (60 seconds)

Nineteen species of bats have been recorded in Canada, and 17 of them are regular residents. In many ways, bats are typical mammals: they are warm-blooded, give birth to live young and suckle them. Their ability to fly sets them apart from all other mammals. Their wings are folds of skin supported by elongated finger, hand, and arm bones. Wing membranes attach to the sides of the body and the hind legs. In Canadian species, the tail is enclosed in the membranes. Resting bats usually hang head downward so that taking flight means just letting go.

With their wings spread, flying bats appear larger than resting ones. But bats are small mammals. For example, an average-sized Canadian bat, the little brown bat Myotis lucifugus, weighs about 8 g in summer (the mass of two nickels and a dime) and has a wingspan of about 22 cm. The hoary bat Lasiurus cinereus is the largest Canadian species, weighing about 30 g, with a wing span of 40 cm. At about 5 g, the smallest Canadian species are the eastern and western small-footed bats (Myotis leibii and Myotis ciliolabrum, respectively).

Bats are long-lived mammals, the current record for being a banded little brown bat from a mine in eastern Ontario that survived more than 35 year.Signs and sounds

Bats are well known for their echolocation behaviour. Most bats — and all Canadian species — use echoes of the sounds they produce to locate objects in their path. Higher frequency sounds have shorter wavelengths and give bats more detailed information about their targets. Most Canadian bat species use echolocation calls that are ultrasonic (beyond the range of human hearing). A notable exception is the spotted bat Euderma maculatum, which occurs in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia and uses lower-frequency echolocation calls readily audible to most people.

-

Stuart Oikawa

Beaver

Beaver Beaver (30 seconds) Beaver (Youth) Beaver (15 seconds)

Stuart Oikawa

Beaver

Beaver Beaver (30 seconds) Beaver (Youth) Beaver (15 seconds)

The beaver Castor canadensis is the largest rodent in North America and the largest rodent in the world except for the capybara of South America. On average, an adult weighs from 16 to 32 kg and, including its 30-cm tail, a large beaver may measure 1.3 m long. Some may even weigh more than 45 kg! Its ancestors were even larger. In the Pleistocene ice age—the era of the mastodons and the mammoths—the giant beavers that inhabited the expanses of Eurasia and North America measured just under 3 m in length, including the tail, and probably weighed 360 kg.

Being short and rotund, the beaver is ungainly and slow on land. Not so in the water. The beaver is a graceful, strong swimmer, both under water and on the surface, attaining speeds approaching 7 km per hour if it is alarmed.

The beaver’s body is adapted in many ways to the animal’s watery habitat. The beady eyes see as well in the water as out of it thanks to a specialized transparent membrane that can be drawn over the eyes for protection while diving. The nostrils are small and can be closed for underwater swimming, as can the ears.

The beaver’s tail has important uses both in the water and on land. The tail of a large beaver may be 30 cm long, up to 18 cm wide, and 4 cm thick. It is covered with leathery scales and sparse, coarse hairs. Although fat, the tail is flexible and muscular. In the water, the animal can use its tail as a four-way rudder. On land, the tail acts as a prop when the beaver is sitting or standing upright. It also serves as a counterbalance and support when the animal is walking on its hind legs while carrying building materials like mud, stones, or branches with its front paws.

The beaver’s hind feet are very large, with five long blunt-clawed toes which are fully webbed, for swimming. In the water, the beaver holds its forepaws close to its body, using only its hind feet to propel itself, with occasional aid from its tail. Its forepaws are small, without webs, and the toes end in long sharp claws suited to digging. These delicate paws are very dexterous—almost like hands—and with them the beaver can hold and carry sticks, stones, and mud and perform a variety of complex construction tasks.

The beaver also uses its paws to groom its coat. The second toe on each hind foot is double-clawed, the claws being hinged to come together like tiny pliers. These specialized claws, along with the front claws, are used for grooming the fur, which is brown in colour. -

Wolfgang Jansen

Beluga Whale

Beluga Beluga, 30 sec Beluga, 15 sec Beluga, 30 sec Youth

Wolfgang Jansen

Beluga Whale

Beluga Beluga, 30 sec Beluga, 15 sec Beluga, 30 sec Youth

With its pure white skin and prominent, bulging forehead, the beluga whale is easy to spot. Beluga actually means ‘the white one’ in Russian. However, only adult belugas are white; calves are born brown or dark grey and gradually pale to become totally white between six and eight years of age.

Beluga whales have stout bodies, well-defined necks and a disproportionately small head. They have thick skins, short but broad paddle-shaped flippers, and sharp teeth. Unlike other whales, the beluga doesn’t have a dorsal fin. Belugas average 3 to 5 metres in length and weigh between 500 and 1,500 kilograms. Male whales have a marked upward curve at the top of their flippers.

-

Micheal Dockery

Black Bear

Black Bear

Micheal Dockery

Black Bear

Black Bear

The black bear Ursus americanus is one of the most familiar wild animals in North America today. Black bears are members of the family Ursidae, which has representatives throughout most of the northern hemisphere and in some parts of northern South America. Other members of this family that occur in North America are grizzly bears and polar bears. Both of these species are considerably larger than the black bear.

The black bear is a bulky and thickset mammal. Approximately 150 cm long and with a height at the shoulder that varies from 100 to 120 cm, an adult black bear has a moderate-sized head with a rather straight facial profile and a tapered nose with long nostrils. The ears are rounded and the eyes small. The tail is very short and inconspicuous.

A black bear has feet that are well furred on which it can walk, like a human being, with the entire bottom portion of the foot touching the ground. Each foot has five curved claws, which the bear cannot sheathe, or hide. These are very strong and are used for digging and tearing out roots, stumps, and old logs when searching for food.

Because bears are compact, they often appear much heavier than they really are. Adult males weigh about 135 kg, although exceptionally large animals weighing over 290 kg have been recorded. Females are much smaller than males, averaging 70 kg.

The normal colour is black with a brownish muzzle and frequently a white patch below the throat or across the chest. Although black is the most common colour, there are other colour phases, such as brown, dark brown, blond, cinnamon, and blue-black. Albino bears (having white fur and red eyes and noses) also occur, but they are rare. A unique non-albino white phase black bear population occurs on the Kermode islands, off the Pacific coast in British Colombia. The lighter colour phases are more common in the west and in the mountains than in the east. Any of these colour phases may occur in one litter, but generally all cubs in a litter are the same colour as their mother.

-

J. Michael Lockhart,USFWS

Black-Footed Ferret

J. Michael Lockhart,USFWS

Black-Footed Ferret

Of the three ferret species in the world, the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) is the only one indigenous to North America. In contrast, the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius) is of European origin, though both species belong to the mustelid family, which also includes the mink, weasel, otter, wolverine and one of the black-footed ferret’s main predators, the badger.

Black-footed ferrets are impeccably cute: cat-like whiskers sprouting from a white muzzle, plush round ears above eyes set into a bandit’s black mask and sturdy legs in black stockings, supporting a sinuous, sandy-coloured body crowned by a black-tipped tail.

Their shape, colouring and behaviour are all finely tuned for life in the grasslands. Their yellow-buff fur blends so seamlessly with the prairie landscape that they can be hard to spot while immobile, which protects them from predators like badgers, foxes and coyotes. They can slide into prairie dog burrows with their long, slinky bodies and use their sharp teeth, strong jaws and non-retractable claws to kill and devour the occupants. They then make comfortable shelters of these burrows, their long necks allowing them to check for above-ground threats before emerging.

Black-footed ferrets measure 28 to 50 centimetres, and their tails are between 11 and 15 centimetres long. Males weigh from 950 to 1,100 grams, while females weigh from 750 to 900 grams. The ferrets’ concave ears and large eyes give them an acute sense of hearing and sight, while their nose is specially developed to detect prairie dogs underground during their nocturnal hunts. Like all members of the mustelid family, black-footed ferrets have scent glands under their tales, which secrete a musk useful for marking territory.

Black-footed ferrets measure 28 to 50 centimetres, and their tails are between 11 and 15 centimetres long. Males weigh from 950 to 1,100 grams, while females weigh from 750 to 900 grams. The ferrets’ concave ears and large eyes give them an acute sense of hearing and sight, while their nose is specially developed to detect prairie dogs underground during their nocturnal hunts. Like all members of the mustelid family, black-footed ferrets have scent glands under their tales, which secrete a musk useful for marking territory. Signs and sounds

Black-footed ferrets make a high-pitched chatter to express anxiety or excitement. During their release into the wild (see “Conservation”), when captive-bred ferrets were hesitant to leave the perceived safety of the travel case, their anxious chatter warned handlers against giving them an encouraging nudge.As their library of sounds and signs suggests, black-footed ferrets are very playful, especially while young. Females whimper and chortle to corral their kits, who wrestle, chase one another and occasionally engage in a mischievous “Ferret Dance,” in which they arch their backs, open their mouths and hop backwards.

-

Corey Accardo (NOAA)

Bowhead Whale

Corey Accardo (NOAA)

Bowhead Whale

The Bowhead whale was named for its distinctive bow-shaped skull, which is enormous—close to 40 percent of total body length can grow up to 20 metres in length. The whale is mainly blue-black in colour, with cream-colour blotches on its lower jaw, white blotches on its belly, and a pale grey area on its tail. Flippers are small and rounded, and the bowhead has no dorsal fin. Females are generally larger than males.

-

Adam Houben

Canada Lynx

Canada Lynx Canada Lynx (30 seconds) Canada Lynx (youth) Canada Lynx (15 seconds)

Adam Houben

Canada Lynx

Canada Lynx Canada Lynx (30 seconds) Canada Lynx (youth) Canada Lynx (15 seconds)

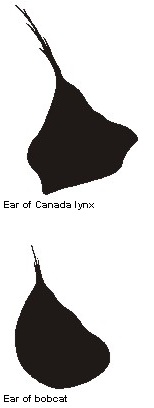

The Canada lynx Lynx canadensis is a beautiful wild felid, or cat, of the boreal forest, or northernmost forest in the Northern Hemisphere. The lynx resembles a very large domestic cat. It has a short tail, long legs, large feet, and prominent ear tufts. Its winter coat is light grey and slightly mottled with long guard hairs; the underfur is brownish, and the ear tufts and tip of the tail are black. The summer coat is much shorter than the winter coat and has a definite reddish brown cast.

The Canada lynx Lynx canadensis is a beautiful wild felid, or cat, of the boreal forest, or northernmost forest in the Northern Hemisphere. The lynx resembles a very large domestic cat. It has a short tail, long legs, large feet, and prominent ear tufts. Its winter coat is light grey and slightly mottled with long guard hairs; the underfur is brownish, and the ear tufts and tip of the tail are black. The summer coat is much shorter than the winter coat and has a definite reddish brown cast.Its large feet, which are covered during winter by a dense growth of coarse hair, help the lynx to travel over snow. The lynx, like the snowshoe hare, can spread its toes in soft snow, expanding its "snowshoes" still farther.

The lynx has large eyes and ears and depends on its acute sight and hearing when hunting. The lynx’s claws, like those of most other cats, are retractable and used primarily for seizing prey and fighting.

Of the three Canadian members of the cat family (Felidae)—the lynx, the bobcat, and the cougar—the lynx and the bobcat are most alike and are most closely related to each other. They probably both descended from the larger Eurasian lynx. There are small differences in appearance: on average, bobcats are slightly smaller; the bobcat’s feet are not as large as those of the lynx, making the bobcat less able to secure food in deep snow; the lynx’s tail has a solid black tip, whereas that of the bobcat has three or four narrow black bars and a black spot near the tip on its upper surface; and the bobcat’s fur has more pronounced spotting. The cougar is much larger and more powerful than either of them, and can be readily identified by its long tail.

Signs and sounds

The lynx has a variety of vocalizations, like those made by house cats, but louder. -

Dave Gallagher

Caribou

Caribou (30 seconds) Caribou (60 seconds)

Dave Gallagher

Caribou

Caribou (30 seconds) Caribou (60 seconds)

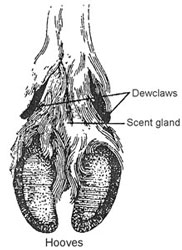

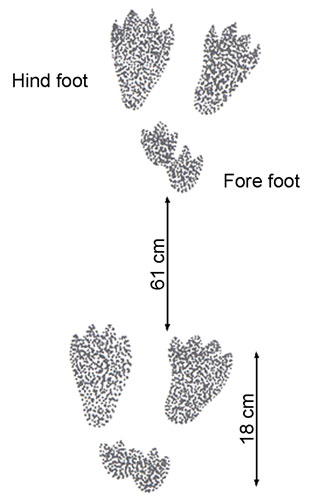

Figure 1: Base of caribou footThe caribou Rangifer tarandus is a medium-sized member of the deer family, Cervidae, which includes four other species of deer native to Canada: moose, elk, white-tailed deer, and mule deer. All are ungulates, or cloven-hoofed cud-chewing animals. However, only in caribou do both males and females carry antlers. Caribou are similar to and belong to the same species as the wild and domesticated reindeer of Eurasia.

The caribou is well adapted to its environment. Its short, stocky body conserves heat, its long legs help it move through snow, and its long dense winter coat provides effective insulation, even during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are short and well haired.

Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. In fact, the name “caribou” may be linked to this ability—it may be a corruption of the Mi’kmaq name for the animal, “xalibu,” which means “the one who paws.” The sharp edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers and their hooves function well as paddles. In winter, the hooves grow to a remarkable length, giving the animal firm footing on crusty snow. In summer, the hooves are worn away by travel over hard ground and rocks. The dewclaws, or small toes, are large, widely spaced, and set back on the foot, greatly increasing the weight-bearing area. Scent glands located at the base of the ankles are used when the caribou is in danger: the animal rears up on its hind legs and deposits a scent that alerts other caribou to the menace. (See Figure 1.)

-

Megan Lorenz

Chipmunk

Chipmunk

Megan Lorenz

Chipmunk

Chipmunk

Chipmunks Tamias are easily recognized by the light and dark stripes on the back and head. They can be confused with some of the striped ground squirrels, but chipmunks are smaller, and have facial markings and five dark stripes on their backs, including a distinct, central line that extends forward onto the head. Ground squirrels do not have markings on the head.

The eastern chipmunk is a colourful and attractive rodent with bright russet on its hips, rump, and tail; black, grey, and white stripes on its back; brown, grey, and buff on its head; white underparts; and brown feet. The western chipmunk species are arrayed in shades of grey, brown, reddish, white, and buff and share a distinctive pattern of black, pale grey, and buff stripes, although in the Townsend’s chipmunk the colour contrasts of the stripes are masked by a warm brown overall wash. The red-tailed chipmunk is the most brightly coloured of the western species.

The eastern chipmunk is large (up to 125 g) with a relatively short tail (about one-third of the total length from its nose to the tip of its tail), whereas western chipmunks are smaller (about 55 g) with a relatively longer tail (nearly half the total length from its nose to the tip of its tail). The eastern chipmunk is between 20 and 30 cm long, and western species are 16 to 28 cm long.

Signs and sounds

Chipmunks are quite vocal. People walking in the woods do not always realize that they are hearing chipmunks, for some of the cries that chipmunks make are like bird chirps.

Biologists have not yet determined the meaning of all the chipmunk’s many calls. For example, when a chipmunk is startled, it runs quickly along the ground giving a rapid series of loud chips and squeaks. Perhaps this sudden burst of noise startles predators, helping the chipmunk to escape. Also, chipmunks frequently call with a high-pitched chip or chuck repeated over and over at intervals of one or two seconds. This scolding noise is often made by a chipmunk watching an intruder from a safe vantage point. Some scientists think that it may also be the mating call of the female chipmunk. -

Linda Finstad

Cougar

Cougar

Linda Finstad

Cougar

Cougar

The cougar Puma concolor is one of only three wild felid species, or members of the cat family, found in Canada. Larger than the other two, the lynx and the bobcat, it is also the second largest cat in the New World. The jaguar is the largest.

The cougar Puma concolor is one of only three wild felid species, or members of the cat family, found in Canada. Larger than the other two, the lynx and the bobcat, it is also the second largest cat in the New World. The jaguar is the largest.In the past, the North American cougar was separated into four subspecies. Recent taxonomic research suggests that all North American cougars are essentially the same species, although there are some genetic and morphological differences related to geographic location.

The cougar has a lithe, muscular, compact, and deep-chested body, with a rounded and shortened head and very visible whiskers. It has large eyes with round pupils, an adaptation to the cougar’s nocturnal, or night time, behaviour. Another distinctive characteristic of the cougar is its long tail: measuring up to a metre long, it is important for balance. It distinguishes the cougar from the lynx and the bobcat.

Cougars vary considerably in size and weight throughout their range, with individuals being larger and heavier in North America than in South America. Across the cougar’s range, adult males typically weigh almost one and a half times more than females. In southwestern Alberta, for example, average weights for adult males and females are 71 kg and 4l kg, respectively. In North America, the total body length of adult male cougars is slightly more than 2 m and of adult females, slightly less than 2 m.

Cougars in North America have short fur ranging in colour from reddish, greyish, or tawny to dark brown. The backs of the ears and the tip of the tail are black, and there are black markings on the face. Kittens are spotted at birth, but lose the spots before the end of their first year.

The cougar is well adapted for grasping and cutting up large prey, with extremely strong forequarters and neck. Its muscular jaws, wide gape, and long canine teeth are designed for clamping down and holding onto prey larger than itself, and its teeth are specially adapted for cutting meat and sinews.

Like all members of the cat family, cougars have five digits on their forepaws (including the dewclaw) and four digits on their hind paws. Each digit is equipped with a claw that remains hidden when the animal is walking but that is used with deadly effectiveness when grasping prey. The cougar’s front feet and claws are larger than its hind parts, allowing it to clutch large prey.

The cougar is known by many names, depending on local culture and legend. The Maliseet of New Brunswick call the cougar “pi-twal,” meaning “the long-tailed one.” English settlers along the Atlantic coast gave it the name “panther” after the Old World panther, which they had seen in animal shows, zoos, and artworks. The French explorers of southern Quebec and New Brunswick called it the “carcajou,” a name later given to the wolverine, causing great confusion between the two species in writings about them. The English name “cougar” and the French “couguar,” now widely used in Canada, were adapted from the Brazilian native name “cuguacuarana.” The name “mountain lion” is extensively used in the western United States, and “puma” is the native Peruvian name.

Signs and sounds

Normally a silent hunter, the cougar, like any cat, becomes vocal during the breeding season. Females in heat yowl.

-

David Cracknell

Coyote

David Cracknell

Coyote

The coyote Canis latrans is one of the seven representatives of the Canidae family found in Canada. Other members of the family are the wolf, red fox, arctic fox, grey fox, swift fox, and dog.

Slimmer and smaller than the wolf, the male coyote weighs from 9 to 23 kg, has an overall length of 120 to 150 cm (including a 30- to 40-cm tail), and stands 58 to 66 cm high at the shoulder. The female is usually four-fifths as large.

The coyote’s ears are wide, pointed, and erect. It has a tapering muzzle and a black nose. Unlike most dogs, the top of the muzzle on coyotes forms an almost continuous line with the forehead. The yellow, slightly slanting eyes, with their black round pupils, give the coyote a characteristic expression of cunning. The canine, or pointed, teeth are remarkably long and can inflict serious wounds. The neck is well furred and looks oversized for the body. The long tongue often hangs down between the teeth; the coyote regulates its body temperature by panting.

The paw, more elongated than that of a dog of the same size, has four toes with nonretractable claws. The forepaws show a rudimentary thumb, reduced to a claw, located high on the inner side. The claws are not used in attack or defence; they are typically blunted from constant contact with the ground and do not leave deep marks.

The fur is generally a tawny grey, darker on the hind part of the back where the black-tipped hair becomes wavy. Legs, paws, muzzle, and the back of the ears are more yellowish in colour; the throat, belly, and the insides of the ears are whiter. The tail, darker on top and lighter on the underside, is lightly fawn-coloured towards the tip, which is black.

The coyote’s fur is long and soft and well suited to protect it from the cold. Because it is light-coloured in winter and dark in summer, it blends well with the seasonal surroundings.

Like all Canidae, the coyote has, at the root of the tail, a gland that releases a scent. Such glands also exist on other parts of the body. Scent glands often become more active when the animals meet. The coyote’s urine has a very strong smell and is used to mark out its territory. Trappers use the secretions when they set traps to attract the coyote. -

Sonia Fox

Eastern Grey Squirrel

Sonia Fox

Eastern Grey Squirrel

Eastern grey squirrels Sciurus carolinensis commonly occur in two colour phases, grey and black, which leads people to think—mistakenly—that there are two different species. Black is often the dominant colour in Ontario and Quebec, toward the northern limits of the species’ range. Farther south the black phase is less common and is not found at all in the southern United States. This may indicate that the gene responsible for black coloration has some cold-weather adaptation associated with it. Albino eastern grey squirrels also occur and in the United States a few small, completely white populations are found. There are rare instances of a reddish colour phase and some animals may also have a combination of colours, for example a black body with a red tail. These individuals should not be confused with the American red squirrel Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, which is common to Canada’s northern forests, nor with Douglas’s squirrel T. douglasii, found in British Columbia. Both of these are smaller animals with a rusty red colour on the body, head, and tail.

The squirrel’s fur is thicker and longer in winter. The fur colour is grey or black and may change with the seasons. The grey fur is a grizzled salt-and-pepper combination produced by lead-grey underfur, overlain by banded grey and black guard hairs tipped with white. Black individuals are generally a glossy uniform black all over, but the species may show all shades of gradation between black and grey. A litter may contain both black and grey individuals.

The most notable physical feature of the eastern grey squirrel is its large bushy tail. Indeed, the Latin word for squirrel, sciurus, is derived from two Greek words, skia, meaning shadow, and oura, meaning tail. Combining the two means loosely that the squirrel is one that sits in the shadow of its own tail. Many of the common names given to the eastern grey squirrel, such as Bannertail and Silvertail, call attention to this prominent feature.

The tail has many important functions. It acts as a rudder when the animal jumps from high places, as a warm covering during the winter, as a signal to other eastern grey squirrels indicating an individual’s mood, and perhaps as a sunshade. Finally, the tail can be used to distract a pursuing predator. -

Rolf Gary Phillips

Grizzly Bear

Grizzly Grizzly (15 seconds) Grizzly (Youth) Grizzly (30 seconds) Grizzly

Rolf Gary Phillips

Grizzly Bear

Grizzly Grizzly (15 seconds) Grizzly (Youth) Grizzly (30 seconds) Grizzly

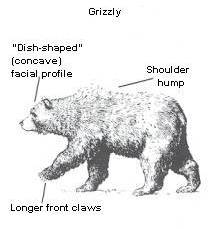

The grizzly (Ursus arctos) is the second largest North American land carnivore, or meat-eater, and, like the larger polar bear, has a prominent hump over the shoulders formed by the muscles of its massive forelegs.

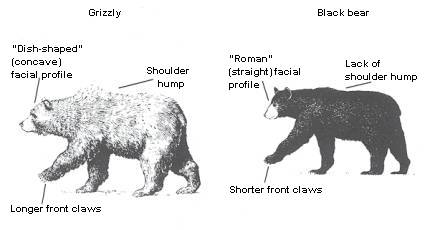

The Grizzly’s unique features are its somewhat dished face and its extremely long front claws (see sketch). Its colour ranges from nearly white or ivory yellow to black. Some are of uniform colour, but many Grizzlies have light or grizzled fur on the head and shoulders, a dark body, and sometimes darker feet and legs. The body shape and long fur tend to make Grizzlies look heavier than they actually are. Although Grizzly Bears have been known to weigh as much as 500 kg, the average male weighs 250 to 350 kg and the female about half that.

Grizzly Bear and Black Bear Comparison: The bear family includes seven species found in both the western and eastern hemispheres, and in South America. The brown bear Ursus arctos is one of the three species of bear found in North America. The other two are the polar bear Ursus maritimus and the black bear Ursus americanus. The Grizzly has certain unique characteristics, and at first scientists thought that it was a different species from the very similar European brown bear. But, in 1953, they assigned it to the same species as brown bears found in Europe and Asia.

Grizzly Bear and Black Bear Comparison: The bear family includes seven species found in both the western and eastern hemispheres, and in South America. The brown bear Ursus arctos is one of the three species of bear found in North America. The other two are the polar bear Ursus maritimus and the black bear Ursus americanus. The Grizzly has certain unique characteristics, and at first scientists thought that it was a different species from the very similar European brown bear. But, in 1953, they assigned it to the same species as brown bears found in Europe and Asia.

There are two recognized subspecies of the circumpolar brown bear Ursus arctos in North America. The Kodiak bear found on the Kodiak Islands of Alaska (Ursus arctos middendorffi) is one. All the rest, though they may differ in size because of geographic differences in the quantity and quality of food, are Grizzlies.

Signs and sounds

Grizzly Tracks -

Chiara Giulia Bertulli,University of Iceland, Faxafloi Cetacean Research

Harbour Porpoise

Chiara Giulia Bertulli,University of Iceland, Faxafloi Cetacean Research

Harbour Porpoise

Rarely reaching lengths greater than 1.7 metres, harbour porpoises weigh an average of 90 kilograms. Females grow more quickly and are larger than males.

Porpoises have rounded heads and a small triangular dorsal fin at the middle of their backs. Its mottled greyish-white sides fade to almost white along its belly, helping it blend well into the marine environment. A black ‘cape’ extends over the back and sides of the harbour porpoise. Some may also have dark patches on the face.

There is no difference in coloring between males and females; however calves are usually darker than adults.

-

Lance Underwood

Killer Whale

Killer Whale (30 seconds) Killer Whale (60 seconds)

Lance Underwood

Killer Whale

Killer Whale (30 seconds) Killer Whale (60 seconds)

Without a doubt, the killer whale (Orcinus orca) is one of the most distinctive marine mammals in the world. Its size — six to eight metres long and between four and five tonnes in weight — and its striking black-and-white colouring, and long, rounded body make it unmistakable. The first sight of a killer whale is often the tall dorsal fin. In fully grown males, this fin sticks straight up, often as high as 1.8 metres. In females and young whales, the fin is curved and less than one metre high. Behind the dorsal fin is a grey area called a saddle patch. The shape of the dorsal fin and saddle patch, as well as natural nicks and scars on them, are unique to each killer whale.

-

Jeremy Gatten

Lemmings

Jeremy Gatten

Lemmings

Lemmings are mouselike rodents that live in treeless areas of northern Canada. They have short ears, largely hidden in the fur, short legs, and short tails. Adult brown lemmings are about 150 mm in total length, including about 20 mm of tail. Their body weight varies from about 55 g in some years to about 115 g in others. Their fur is a full brown and grey summer and winter. Collared lemmings are the same overall size as brown lemmings but with a shorter tail (about 15 mm). Their colour changes with the seasons (hence their other common name, “varying lemming”). In summer, a collared lemming has a black nose, grey cheeks, tawny ear spots, a chestnut collar, and a more or less prominent black dorsal stripe. With the autumn moult, however, the summer coat is replaced by a solid white winter one and the front feet develop two greatly enlarged claws, presumably to help dig through the hard-packed tundra snow.

Unique characteristics

Lemming populations have long been known to fluctuate drastically. Peak numbers tend to recur about every four years. Furthermore, numbers are high over a huge area: for example, 1960 was a "lemming year" for almost all of the Canadian Arctic. All sorts of reasons for the cycles have been suggested, from changes in the number of sunspots to snow conditions. Weather is a likely, but still unproven, trigger. Winter creates problems for lemmings, the amount and timing and distribution of snow mitigate those problems, and peak numbers occur only following winter breeding. Unfortunately, no one has yet studied the role of snow cover in sufficient detail to prove that it causes the cycle. We do know that on Devon Island in Nunavut, collared lemmings bred during winter 1972–73, when the temperature under the snow fell below -20°C, and their population peaked the following spring.A remarkable feature of the lemming cycle is the extreme scarcity of individuals at the "low point" of the cycle. Although several species of small rodents that live in temperate climates also reach peaks of abundance about every four years and some of them reach much higher densities at the peak than lemmings do, none can equal the extreme scarcity of lemmings at the low point. Such extreme scarcity raises the possibility of extinction. But passing through a population "bottleneck" probably strongly favours the individuals best adapted to survival in harsh arctic conditions. The cycle of every four years or so may be a device to keep selection abreast of the changes continually going on in the Arctic.

-

Thinkstock

Little Brown Bat

Little Brown Bat (30 seconds) Little Brown Bat (60 seconds)

Thinkstock

Little Brown Bat

Little Brown Bat (30 seconds) Little Brown Bat (60 seconds)

Little Brown Bat

The Little Brown Bat, or Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) weighs between 7 and 9 g, and has a wingspan of between 25 and 27 cm. Females tend to be slightly larger than males but are otherwise identical. As its name implies, it is pale tan to reddish or dark brown with a slightly paler belly, and ears and wings that are dark brown to black.

Contrary to popular belief, Little Brown Bats, like all other bats, are not blind. Still, since they are nocturnal and must navigate in the darkness, they are one of the few terrestrial mammals that use echolocation to gather information on their surroundings and where prey are situated. The echolocation calls they make, similar to clicking noises, bounce off objects and this echo is processed by the bat to get the information they need. These noises are at a very high frequency, and so cannot be heard by humans.

-

Anna Bogucka

Marten

Anna Bogucka

Marten

The marten Martes americana, a small predator, is a member of the weasel family, Mustelidae. It is similar in size to a small cat but has shorter legs, a more slender body, a bushy tail, and a pointed face. The fur varies from pale yellowish buff to dark blackish brown. During winter, the marten has a beautiful dark brown fur coat and a bright orange throat patch. The summer coat is lighter in colour and not nearly as thick. Males are the larger sex and weigh about 1 000 g, whereas females weigh about 650 g.

The Mustelidae family also includes several other more familiar animals such as the ermine, skunk, and mink. It is thought that martens entered North America from Asia about 60 000 years ago. There are several species of martens worldwide and perhaps the most famous is the Russian sable, which is well known for its luxurious fur.

Signs and sounds

In winter, the soles of a marten’s feet are covered with fur and the toes are not distinguishable in the tracks. Tracks are about 3.7 cm long and form two ovals that overlap by about one third. This happens because martens travel with a loping sort of gait, and the hind feet land in the tracks left by the front feet. Loping is common among mustelids, and it takes some practice to be able to distinguish the tracks of the various species. -

Derald Lobay

Moose

Moose

Derald Lobay

Moose

Moose

A bull moose in full spread of antlers is the most imposing beast in North America. It stands taller at the shoulder than the largest saddle horse. Big bulls weigh up to 600 kg in most of Canada; the giant Alaska-Yukon subspecies weighs as much as 800 kg. In fact, the moose is the largest member of the deer family, whose North American members also include elk (wapiti), white-tailed deer, mule deer, and caribou.

Moose Alces alces have long, slim legs that end in cloven, or divided, hooves often more than 18 cm long. The body is deep and massively muscled at the shoulders, giving the animal a humped appearance. It is slab-sided and low-rumped, with rather slender hindquarters and a stubby, well-haired tail. The head is heavy and compact, and the nose extends in a long, mournful-looking arch terminating in a long, flexible upper lip. The ears resemble a mule’s but are not quite as long. Most moose have a pendant of fur-covered skin, about 30 cm long, called a bell, hanging from the throat.

In colour the moose varies from dark brown, almost black, to reddish or greyish brown, with grey or white leg "stockings."

In late summer and autumn, a mature bull carries a large rack of antlers that may extend more than 180 cm between the widest tips but that are more likely to span between 120 and 150 cm. The heavy main beams broaden into large palms that are fringed with a series of spikes usually less than 30 cm long. The antlers are pale, sometimes almost white.

A bull calf may develop button antlers during its first year. The antlers begin growing in midsummer and during the period of growth are soft and spongy, with blood vessels running through them. They are covered with a velvety skin. By late August or early September the antlers are fully developed and are hard and bony. The velvet dries and the bulls rub it off against tree trunks.

Mature animals usually shed their antlers in November, but some younger bulls may carry theirs through the winter until April. Yearling bulls usually have spike antlers, and the antlers of two-year-olds are larger, usually flat at the ends. Moose grow antlers each summer and shed them each autumn.

Signs and sounds

The voice of a newborn calf is a low grunt, but after a few days the calf develops a strident wail that sounds almost human. During the breeding season, or rut, the cow moose entices a mate with a nasal-toned bawling. The bull responds with a coughing bellow. -

Corrine McMahon

Mountain Sheep

Mountain Sheep

Corrine McMahon

Mountain Sheep

Mountain Sheep

The wild, or mountain, sheep is a stocky, hoofed mammal, about one and a half times as large as a domestic sheep. North American wild sheep are related both to domestic sheep Ovis aries, which were imported from Europe by early settlers, and to the native sheep of Asia.

It is thought that about half a million years ago a primitive sheep similar to the present-day Marco Polo sheep of central Asia migrated into North America via the Bering land bridge, which formerly connected the regions now known as Russia and Alaska. When the great glaciers of the ice age inched south from polar centres, those animals became isolated in two ice-free areas, or refugia, one in central Alaska and the other south of the Columbia and Snake rivers, in the United States. Sheep in the Alaska refugium evolved into the slender-horned Dall sheep Ovis dalli, those farther south into the heavy-horned Rocky Mountain and desert bighorns Ovis canadensis.

As the ice sheet retreated 10 000 or 20 000 years ago, the northern sheep expanded their range east to the Mackenzie Mountains and south to the Peace River of northern British Columbia. Gradually, two subspecies, or races, of Dall sheep—one white, the other almost black—evolved. The black Dall sheep is also called the Stone sheep. In the Pelly Mountain area of the Yukon, black and white Dall sheep merge gradually with each other. The curious result, known as the Fannin, or saddle-backed, sheep has a white head, neck, and rump, but a grey body. The southern sheep evolved into seven races, two of which returned to Canada after the retreat of the glaciers. Rocky Mountain and California bighorns are similar in appearance to Dall sheep, except that their coat is usually brown or grey in tone. They both have a white rump patch.

The southern sheep evolved into seven races, two of which returned to Canada after the retreat of the glaciers. Rocky Mountain and California bighorns are similar in appearance to Dall sheep, except that their coat is usually brown or grey in tone. They both have a white rump patch.

The most distinctive characteristic of male mountain sheep is their massive horns, which spiral back, out, and then forward, in an arc. Adult females have slightly curved horns about 30 cm long.

Horns of a Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep measure up to 125 cm in length and 460 mm in circumference at the base. They normally form a tight curl close to the face and are often blunt at the tips. The horns of Dall and Stone sheep are about the same length but are more slender and widely flaring, and usually pointed at the tips. The maximum circumference at the base of the Dall horn is 400 mm. The two horns of a male, with their cones, may weigh over 13 kg.

These horns grow from the skin over a conical bony core and are never shed. They grow throughout life, producing a prominent check line, or annulus, each winter when growth slows. This gives biologists a convenient means of telling age.

Fully adult Rocky Mountain bighorn rams, or males, stand about a metre at the shoulder and weigh up to 136 kg, or slightly more in the autumn when they are in prime physical condition. Average spring weight of adult rams is about 100 kg, of adult ewes, or females, about 63 kg. Dall and Stone sheep are somewhat smaller, adult males averaging less than 90 kg and adult ewes about 50 kg. -

Mathieu Dumond

Muskox

Muskox

Mathieu Dumond

Muskox

Muskox

The muskox Ovibos moschatus lives on Canada’s arctic tundra. Superficially the muskox resembles the bison: humped shoulders and a long black coat accentuate the shortness of its legs. In fact, it is more closely related to sheep and goats.

Although not very tall—the shoulder hump of a standing bull reaches only to about the chest height of a person—muskoxen are relatively heavy owing to their stocky and compact build. The few weights of wild muskoxen available indicate that adult bulls weigh 270 to 315 kg and cows about 90 kg less. Usually slow and deliberate in its movements, the muskox can run and climb with great agility if the need arises. Both cows and bulls have impressive horns. The horns curve downward toward the face, then out and up at the slender tips. On the bulls, the base of each horn extends across the forehead to meet as a solid "boss" of horn and bone up to 10 cm thick. A patch of fur on the forehead separates the less massive but equally sharp horns of the cow. Almost hidden in the wool in front of the eyes is a small scent-producing, pre-orbital gland.

Both cows and bulls have impressive horns. The horns curve downward toward the face, then out and up at the slender tips. On the bulls, the base of each horn extends across the forehead to meet as a solid "boss" of horn and bone up to 10 cm thick. A patch of fur on the forehead separates the less massive but equally sharp horns of the cow. Almost hidden in the wool in front of the eyes is a small scent-producing, pre-orbital gland.

The muskox owes its ability to function normally in temperatures of -40°C in high winds and blowing snow, in large measure, to its amazing coat. The coat has both a woolly layer and a hairy layer. The insulating woolly layer is next to the skin. The wool, or "qiviut," is stronger than sheep’s wool, eight times warmer, and finer than cashmere. The coarser hairy layer that covers and protects the wool grows to be the longest hair of any mammal in North America. The Inuit name for muskox is omingmak, "the animal with skin like a beard."

In midsummer, muskoxen lose their woolly undercoats. The long guard hairs are not shed at the same time. The animals become shaggy and ragged-looking for a few weeks. Many adult bulls have clumps of old wool clinging to their "skirts" and manes throughout the year.

The muskoxen’s rounded hooves are another physical adaptation to its environment. They spread enough to help prevent the animal sinking into soft snow, although they are not as broad as those of caribou. The front hooves are larger than the hind hooves and enable the muskox to dig through the snow for food.

Signs and sounds

During the breeding season bulls frequently utter deep, rumbling roar-like bellows that serve as a challenge to other males. -

Debbie Oppermann

Muskrat

Debbie Oppermann

Muskrat

The muskrat Ondatra zibethicus is a fairly large rodent commonly found in the wetlands and waterways of North America. It has a rotund, paunchy appearance. The entire body, with the exception of the tail and feet, is covered with a rich, waterproof layer of fur. The short underfur is dense and silky, while the longer guard hairs are coarser and glossy. The colour ranges from dark brown on the head and back to a light greyish-brown on the belly. A full-grown animal weighs on the average about 1 kg but this varies considerably in various parts of North America. The length of the body from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail is usually about 50 cm. The tail is slender, flattened vertically and up to about 25 cm long. It is covered with a scaly skin that protects it from physical damage.

Only a minimal amount of hair grows on the feet. The hand-like front feet are used in building lodges, holding food, and digging burrows and channels. Although the larger hind feet are used in swimming, they are not webbed like those of the beaver and otter. Instead, the four long toes of each foot have a fringe of specialized hairs along each side, giving the foot a paddle-like effect. The rather small ears are usually completely hidden by the long fur. The four chisel-like front teeth (two upper and two lower incisors), each up to 2 cm long, are used in cutting stems and roots of plants.

The muskrat’s name is derived from the fact that the animal has two special musk glands—also called anal glands—situated beneath the skin in the region of the anus. These glands enlarge during the breeding season and produce a yellowish, musky-smelling substance that is deposited at stations along travel routes used by muskrats. Common sites of deposition are "toilets," bases of lodges, and conspicuous points of land. The biology of musk glands has not been studied extensively, but the odour produced is believed to be a means of communication among muskrats, particularly during the breeding season.

Signs and sounds

In the spring, during the mating season, sharp whining noises and occasional sounds of fighting may be heard.

-

Glenn Williams

Narwhal

Narwhal (30 seconds) Narwhal (60 seconds)

Glenn Williams

Narwhal

Narwhal (30 seconds) Narwhal (60 seconds)

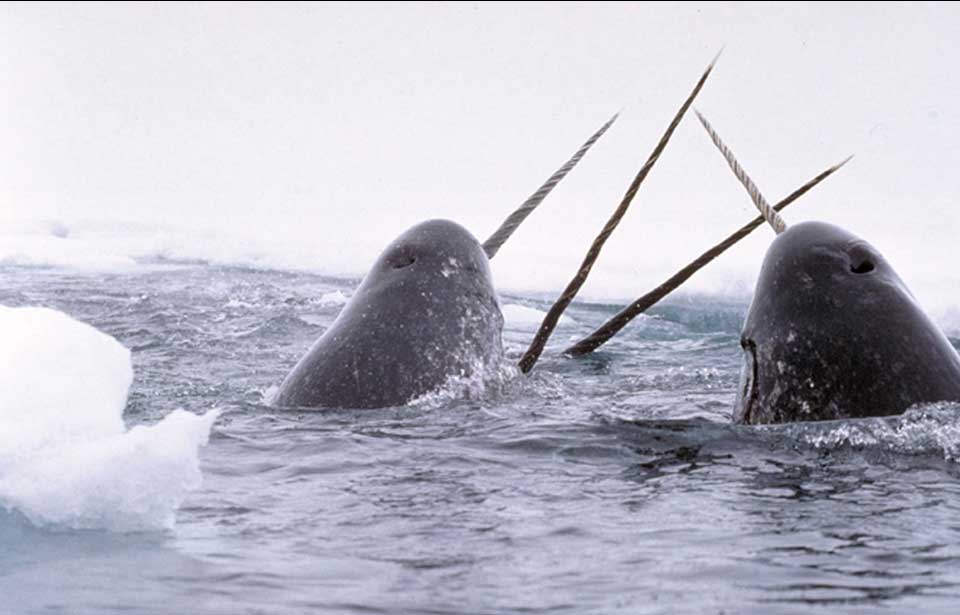

Narwhals (Monodon monoceros) are considered medium-sized odontocetes, or toothed whales (the largest being the sperm whale, and the smallest, the harbour porpoise), being of a similar size to the beluga, its close relative. Males can grow up to 6.2 m -the average size being 4.7 m- and weigh about 1,600 kg. Females tend to be smaller, with an average size of 4 m and a maximum size of 5.1 m and weigh around 900 kg. A newborn calf is about 1.6 m long and weighs about 80 kilograms. The narwhal has a deep layer of fat, or blubber, about 10 cm thick, which forms about one-third of the animal’s weight and acts as insulation in the cold Arctic waters.

Like belugas, they have a small head, a stocky body and short, round flippers. Narwhals lack a dorsal fin on their backs, but they do have a dorsal ridge about 5 cm high that covers about half their backs. This ridge can be used by researchers to differentiate one narwhal from another. It is thought that the absence of dorsal fin actually helps the narwhal navigate among sea ice. Unlike other cetaceans –the order which comprises all whales–, narwhals have convex tail flukes, or tail fins.

These whales have a mottled black and white, grey or brownish back, but the rest of the body (mainly its underside) is white. Newborn narwhal calves are pale grey to light brownish, developing the adult darker colouring at about 4 years old. As they grow older, they will progressively become paler again. The narwhal’s colouring gives researchers an idea about how old an individual is. Some may live up to 100 years, but most probably live to be 60 years of age.

The narwhal’s most striking feature is undoubtedly its tusk. This long, spiral upper incisor tooth (one of the two teeth narwhals have) grows out from the animal’s upper jaw, and can measure up to 3 m and weigh up to 10 kg. Although the second, smaller incisor tooth often remains embedded in the skull, it rarely but on occasion develops into a second tusk. Tusks typically grow only on males, but a few females have also been observed with short tusks. The function of the tusk remains a mystery, but several hypotheses have been proposed. Many experts believe that it is a secondary sexual character, similar to deer antlers. Thus, the length of the tusk may indicate social rank through dominance hierarchies and assist in competition for access to females. Indeed, there are indications that the tusks are used by male narwhals for fighting each other or perhaps other species, like the beluga or killer whale. A high quantity of tubules and nerve endings in the pulp –the soft tissue inside teeth – of the tusk have at least one scientist thinking that it could be a highly sensitive sensory organ, able to detect subtle changes in temperature, salinity or pressure. Narwhals have not been observed using their tusk to break sea ice, despite popular belief. Narwhals do occasionally break the tip of their tusk though which can never be repaired. This is more often seen in old animals and gives more evidence that the tusk might be used for sexual competition. The tusk grows all throughout a male’s lifespan but slows down with age.

-

Annette Hill

North American Bison

American Bison American Bison (30 seconds) American Bison (15 seconds) American Bison (Youth) The Bison

Annette Hill

North American Bison

American Bison American Bison (30 seconds) American Bison (15 seconds) American Bison (Youth) The Bison

The North American bison, or buffalo, is the largest land animal in North America. A bull can stand 2 m high and weigh more than a tonne. Female bison are smaller than males.

The North American bison, or buffalo, is the largest land animal in North America. A bull can stand 2 m high and weigh more than a tonne. Female bison are smaller than males.

A bison has curved black horns on the sides of its head, a high hump at the shoulders, a short tail with a tassel, and dense shaggy dark brown and black hair around the head and neck. Another distinctive feature of the buffalo is its beard.

There are two living subspecies of wild bison in North America: the plains bison Bison bison bison and the wood bison Bison bison athabascae.The drawings show some of the features that biologists look for if they wish to identify a bison by subspecies. In general, the plains bison is lighter in colour than the wood bison. The wood bison is taller, longer legged, and less stockily built than the plains bison, but it is heavier.

Signs and sounds

During the mating season, from July to mid-September, "bull roarings" are heard for kilometres, day and night, as bulls challenge each other in the rutting ritual of the mating season. -

Kay-Liam Dunn

North American Elk

Kay-Liam Dunn

North American Elk

The North American elk, or wapiti, is the largest form of the red deer species Cervus elaphus. In general appearance elk are obviously kin to the well-known white-tailed deer. However, elk are much larger. Among Canadian deer, they are second in size only to the moose. An adult bull elk stands about 150 cm tall at the shoulder and weighs about 300 to 350 kg, although some large bulls approach 500 kg in late summer before the rut, or breeding season. Cows are substantially smaller but still have a shoulder height of 135 cm and an adult weight of around 250 kg.

The colour of the elk’s coat ranges from reddish brown in summer to dark brown in winter. Although it looks white from a distance, on closer inspection the rump colour is ivory to orange. In contrast to the rump, the head and neck are dark. Elk have long, blackish hair on the neck that is referred to as a mane.

Male elk are notable for their impressively large antlers. It is amazing that these large structures are grown new each year by the animals in a period of a few months in spring and summer. Antlers look particularly large in summer when they are encased in velvet—a covering that protects them during growth. In later summer, the velvet is rubbed from the fully grown antlers, revealing the bony structure. Newly cleaned antlers are light grey in colour but become stained by rubbing and thrashing through vegetation during the rutting season.

"Elk" is the name by which most Canadians know this majestic deer. "Wapiti," meaning "white rump," is the Shawnee Indian name and the common name preferred by scientists, because the animal known as an "elk" in Europe is not a red deer at all but a close relative of the North American moose. Other red deer, smaller and belonging to several subspecies, are found throughout the northern hemisphere: in Scotland and continental Europe, in North Africa, and in Asia.Signs and sounds

Elk Tracks

The elk is highly vocal for an ungulate, or hoofed animal. A person close to a group of elk can hear frequent grunts and squeals as they keep in touch with each other. When alarmed the cows give sharp barks to warn the rest of the group. The whistling roar of rutting bulls is a spine-tingling sound on a frosty autumn morning.

Elk hooves are rounded and their tracks may be confused with those of yearling cattle in range country.

Elk scat, or droppings, like those of other deer, are in the form of pellets in winter, but in summer, when the animals are on new green forage, resemble those of cattle. Closer inspection, however, reveals traces of a pellet structure.

Droppings

-

Moira Brown, New England Aquarium

North Atlantic Right Whale

North Atlantic Right Whale North Atlantic Right Whale (Youth) North Atlantic Right Whale (30 seconds) North Atlantic Right Whale (15 seconds)

Moira Brown, New England Aquarium

North Atlantic Right Whale

North Atlantic Right Whale North Atlantic Right Whale (Youth) North Atlantic Right Whale (30 seconds) North Atlantic Right Whale (15 seconds)

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.For a variety of reasons, including its rarity, scientists know very little about this rather large animal. For example, there is little data on the longevity of Right Whales, but photo identification on living whales and the analysis of ear bones and eyes on dead individuals can be used to estimate age. It is believed that they live at least 70 years, maybe even over 100 years, since closely related species can live as long.

Unique characteristicsThe Right Whale has a bit of an unusual name. It is thought to have been named by whalers as the “right” whale to hunt due to its convenient tendencies to swim close to shore and float when dead. Its name in French is more straightforward; baleine noire, the black whale.

-

Corinne Pomerleau

Polar Bear

Corinne Pomerleau

Polar Bear

With its distinctive massive body and long neck, the polar bear Ursus maritimus is the largest land carnivore, or meat eater. The white coats of the adults often appear cream to yellow against the dazzling whiteness of their home, the arctic pack ice. Adult males measure from 240 to 260 cm in total length and usually weigh from 400 to 600 kg, although they can weigh up to 800 kg—about as much as a small car. They do not reach their maximum size until they are eight to 10 years old. Adult females are about half the size of males and reach adult size by their fifth or sixth year, when most weigh from 150 to 250 kg. Pregnant females can weigh up to 400 or 500 kg just before entering their maternity dens in the fall.

The bodies of polar bears are longer than the bodies of brown bears; their necks and skulls are also longer, but their ears are smaller. Instead of having the characteristic “dished” or concave facial profile of brown bears, polar bears possess a more prominent or “Roman” nose. Their canine teeth are large, and the grinding surfaces of their cheek teeth are jagged, which is an adaptation to a carnivorous diet. Polar bear claws are brownish in colour, short, fairly straight, sharply pointed, and non-retractable.

Signs and sounds

Polar bears use a deep growl to warn off other bears, particularly when defending a food source. They also hiss and snort to show aggression, accompanied by a lowered head and ears laid back. Angry polar bears communicate their displeasure with loud roars and growls. They also emit a "chuffing" sound in response to stress. Mother bears scold their cubs with a low growl or a soft cuff. -

Brian J. Klein

Porcupine

Brian J. Klein

Porcupine

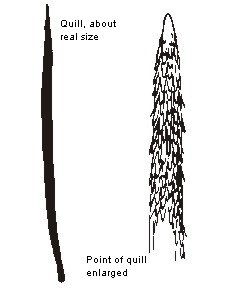

The porcupine Erethizon dorsatum is one of Canada’s best-known mammals, both in life and in legend. Its fame stems from its coat of quills, which keeps most enemies at a respectful distance.

When sitting hunched high up in a tree, a porcupine could be mistaken for the nest of a squirrel or a crow, but close to the ground it is easily recognized. It has a short, blunt-nosed face with small eyes. The ears are small and round, almost concealed by the hair, which also covers the spines. The shoulders are humped, making the back look arched. The short legs are bowed, and the animal stands bear-like with its entire foot planted firmly on the ground. The claws are long and curved. On the hind feet the first digit is replaced by a broad movable pad that allows the animal to grasp branches more firmly when climbing. The muscular tail is thick, short, and rounded at the tip.

The porcupine’s coat consists of a soft, brown, woolly undercoat and coarse, long guard hairs. At the base, each guard hair is brown, becoming darker near the tip, which may be white in eastern populations and yellow in the western ones. The guard hairs conceal the quills until the porcupine is aroused. The quills are longest on the back and tail and when raised push the guard hairs forward, forming a crest. On the face the quills are about 1.2 cm long; on the back they may be up to 12.5 cm in length. There are no quills on the muzzle, legs, or underparts of the body. Each quill is hollow and embedded in the skin, where it is attached to a small muscle that pulls it upright in the fur when the animal bristles with alarm. About 0.6 cm from the tip, the quill tapers to a fine point closely covered by several dozen small black barbs. These barbs feel only slightly rough to the touch, but when they are moist—as when embedded in flesh—they swell, working the quill farther in. The quills have black tips and yellow or white shafts.

Each quill is hollow and embedded in the skin, where it is attached to a small muscle that pulls it upright in the fur when the animal bristles with alarm. About 0.6 cm from the tip, the quill tapers to a fine point closely covered by several dozen small black barbs. These barbs feel only slightly rough to the touch, but when they are moist—as when embedded in flesh—they swell, working the quill farther in. The quills have black tips and yellow or white shafts.

It has been estimated that the porcupine has over 30 000 quills, so it is not incapacitated by a single encounter with an enemy, when several hundred quills may be dislodged. As the quills are lost they are replaced by new ones, which are white and sharp and which remain firmly anchored in the skin until they are fully grown.

The porcupine is Canada’s second largest rodent, next to the beaver. Adult males reach an average weight of 5.5 kg after six years; the females reach 4.5 kg. The total length averages 68 to 100 cm, and the height at the shoulders is about 30 cm. -

Amber Fortowsky

Pronghorn

Pronghorn (Youth) Pronghorn (15 seconds) Pronghorn (30 seconds) Pronghorn

Amber Fortowsky

Pronghorn

Pronghorn (Youth) Pronghorn (15 seconds) Pronghorn (30 seconds) Pronghorn

-

Mickey Watkins

Raccoon

Raccoon

Mickey Watkins

Raccoon

Raccoon

Photo: iStockphoto.com

The common raccoon (Procyon lotor) is probably best known for its mischievous-looking black face mask. Raccoons are usually a grizzled grey in colour with a tail marked by five to 10 alternating black and brown rings. Body coloration can vary from albino, (white) to melanistic (black) or brown. An annual moult, or shedding, of the fur begins in the spring and lasts about three months.

The head is broad with a pointed snout and short rounded ears measuring 4 to 6 cm. The eyes are black. Total body and tail length for adults averages 80 cm; males are generally 25 percent larger than females. Raccoons in northern latitudes tend to be heavier (6 to 8 kg) than their southern counterparts (4 kg). However, fall weights for adults have reached 28 kg in some areas.

-

Gabor Szerencsi

Red Fox

Red Fox

Gabor Szerencsi

Red Fox

Red Fox

The red fox Vulpes vulpes is a small, dog-like mammal, with a sharp pointed face and ears, an agile and lightly built body, a coat of lustrous long fur, and a large bushy tail. Male foxes are slightly larger than females. Sizes vary somewhat between individuals and geographic locations—those in the north tend to be bigger. Adult foxes weigh between 3.6 and 6.8 kg and range in length from 90 to 112 cm, of which about one-third is tail.

Although "red fox" is the accepted common name for the species, not all members of the species are actually red. There are several common colour variations, two or more of which may occur within a single litter. The basic, and most common, colour is red in a variety of shades, with a faint darker red line running along the back and forming a cross from shoulder to shoulder on the saddle. Individuals commonly exhibit some or all of the following markings: black paws, black behind the ears, a faint black muzzle, white or light undersides and throat, a white tail tip, and white stockings.

Other common colours are brown and black. Red foxes that are browner and darker than most of their species and have a cross on the saddle that is dark and prominent are sometimes referred to as "cross foxes." Red foxes that are basically black with white-tipped guard hairs in varied amounts are known colloquially as "silver foxes." Silver foxes are particularly valued by the fur trade, and large numbers were selectively bred in captivity when fox fur clothing was popular.

Signs and sounds

Red foxes have a sharp bark, used when startled and to warn other foxes. -

Annie Langlois

Sea Otter

Sea Otter Sea Otter (Youth) Sea Otter (30 seconds) Sea Otter (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

Annie Langlois

Sea Otter

Sea Otter Sea Otter (Youth) Sea Otter (30 seconds) Sea Otter (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

Sea Otter The Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris) is the smallest marine mammal in North America – males measure 1.2 metres in length and weigh an average of 45 kilograms (females are a bit smaller). At the same time, the Sea Otter is the largest member of its family, the mustelids, which includes River Otters, weasels, badgers, wolverines and martens. It’s also the only member of its family that doesn’t need land at all; it’s completely adapted to life in the water. It may come to land to flee from predators if needed, but the rest of its time is spent in the ocean.

The Sea Otter’s fur is one of the thickest in the animal kingdom, with 150,000 or more hairs per square centimetre. It varies in colour from rust to black. Unlike seals and sea lions, the Sea Otter has little body fat to help it survive in the cold ocean water. Instead, it has both guard hairs and a warm undercoat that trap bubbles of air to help insulate it. The otter is often seen at the surface grooming; in fact, it is pushing air to the roots of its fur.

-

Daniel Dagenais

Snowshoe Hare

Daniel Dagenais

Snowshoe Hare

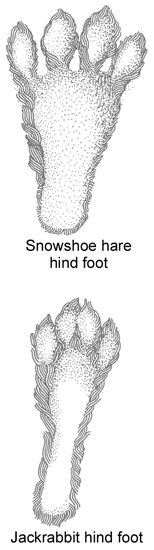

The snowshoe hare Lepus americanus, one of our commonest forest mammals, is found only in North America. It is shy and secretive, often undetected in summer, but its distinctive tracks and well-used trails (“runways” or “leads”) become conspicuous with the first snowfall.

Well-adapted to its environment, the snowshoe hare travels on large, generously furred hind feet, which allow it to move easily over the snow. In soft snow, the four long toes of each foot are spread widely, increasing the size of these “snowshoes” still more. A seasonal variation in fur colour is another remarkable adaptation: from grey-brown in summer, the fur becomes almost pure white in midwinter. The coat is composed of three layers: the dense, silky slate-grey underfur; longer, buff-tipped hairs; and the long coarser guard hairs. The alteration of the coat colour, brought about by a gradual shedding and replacement of the outer guard hairs twice yearly, is triggered by seasonal changes in day length.

The snowshoe hare moults twice a year, beginning in August or September and in March or April. Generally, the hind feet retain patches of white fur into the summer. In the humid coastal zones of southwestern British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, where snow is infrequent, snowshoe hares remain brown throughout the year.

The snowshoe hare’s ears are smaller than most hares’. The ears contain many veins, which help to regulate body temperature; for example, desert hares have very large ears with almost no fur, so the blood can cool in the slightest breeze. Because snowshoe hares live in cold environments, they do not need such big ears to help lower their body temperatures.

Female snowshoe hares are often slightly larger than males. Adult snowshoe hares typically weigh 1.2 to 1.6 kg; the hares are usually heaviest during the peak and early decline of the population cycle.

Signs and sounds

Snowshoe hares are generally silent, but they can show annoyance by snorting. On the rare occasions when they are caught, they utter a high-pitched squeal, which sometimes causes surprised hunters to drop them. During the breeding season, bucks and does (males and females) make a kind of a clicking noise to each other. Does also use this sound to call their young to them for nursing. -

Linda Danyluk

Striped Skunk

Linda Danyluk

Striped Skunk

The striped skunk Mephitis mephitis is about the size of a cat, but has a stout body, a rather small head, short legs, and a bushy tail. Its small head fits conveniently, but sometimes too snugly, into enticing open jars.

The thick, glossy fur is black, with a thin white stripe down the centre of the face and a broad white stripe beginning on the back of the head, forking at the shoulders and continuing as a white stripe along each side of the back to the base of the tail. The tail is mostly black, but the stripes may extend down it, usually to a tuft of white at the tip.

The skunk has long, straight claws for digging out the burrows of mice, ripping apart old logs for grubs and larvae, and digging in the sand for turtle eggs. It moves slowly and deliberately and depends for safety not on running away or on remaining inconspicuous, but on its scent glands.

Skunks belong to the weasel family Mustelidae, all of whose members have well-developed scent glands and a musky odour. The skunk is outstanding for this characteristic, however, and can discharge a bad smelling fluid to defend itself. Indeed its scientific name, mephitis, is a Latin word meaning bad odour.

Signs and sounds

An angry skunk will growl or hiss, and stamp its front feet rapidly. -

Mike Kyffin Jeffery

Swift Fox

Swift Fox

Mike Kyffin Jeffery

Swift Fox

Swift Fox

The swift fox (Vulpes velox), a member of the canid, or dog, family, is related to wolves, coyotes, dogs, and other foxes. It can be distinguished from other kinds of foxes found in Canada, such as red, arctic, and grey foxes, by its small size (it is about the size of a house cat), the black spot on each side of its nose, and its black-tipped tail.

In winter, the swift fox’s fur is long and dense, mainly buff-grey on the head, back, and upper surface of the tail, and orange-tan on the sides, legs, and lower tail surface. The throat, chest, and belly are light coloured (buff to white). In summer, the fur is short and coarse and more reddish grey.

Males are slightly larger than females, average weights being 2.45 and 2.25 kg, respectively. The animal stands about 30 cm high at the shoulder, and its total length is about 80 cm.

Early settlers of the Canadian plains knew the swift fox as the “kit” fox, and the two names have been used interchangeably since that time. However, studies of the prairie kit fox of Canada and the central United States and the desert kit fox of the southwestern United States showed that the two animals have some differences in appearance. Hence, the plains-dwelling species was designated the “swift” fox, and its desert cousin retained the name “kit” fox.

The swift fox can be distinguished from the kit fox Vulpes macrotis by its shorter, more widely spaced ears and its more rounded and dog-like head. The kit fox is broader between the eyes and has a narrower snout. The swift fox also has a slightly shorter tail, averaging of 52 percent of its body length compared with 62 percent for the kit fox. -

Marg Werden

White-Tailed Deer

Marg Werden

White-Tailed Deer

The graceful white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus is well known to most North Americans. Hunters and nonhunters alike recognize the animal by its habit of flourishing its tail over its back, revealing a stark white underside and white buttocks. This "flag" of the white-tailed deer is often glimpsed as the high spirited animal dashes away from people. The tail has a broad base and is almost a foot long. When lowered, it is brown with a white fringe.

The graceful white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus is well known to most North Americans. Hunters and nonhunters alike recognize the animal by its habit of flourishing its tail over its back, revealing a stark white underside and white buttocks. This "flag" of the white-tailed deer is often glimpsed as the high spirited animal dashes away from people. The tail has a broad base and is almost a foot long. When lowered, it is brown with a white fringe.

In summer, the white-tailed deer has a reddish pelage, or fur, on its back and sides and is whitish beneath. In winter the upper parts turn greyish. Full grown male deer frequently exceed 1 m at shoulder height and 110 kg in weight, with exceptional individuals weighing up to 200 kg in the northern part of their range.The antlers of the mature male white-tail consist of a forward curving main beam from which single points project upward and often slightly inward. Perhaps one of every 1 000 females also bears small, simple antlers.

The white-tailed deer is hard to distinguish from the black-tailed deer. The black-tail has similar antlers and will sometimes show the characteristic "flag" of the white-tail but usually with less flare. Fortunately, for identification purposes, the black-tailed deer occurs only west of the Great Divide (its Canadian range is coastal B.C. and Vancouver Island), where the white-tailed deer is uncommon. Confusion is less likely between the white-tailed deer and the darker stockier mule deer. The mule deer can be distinguished by a small white tail with a black tip and antlers that divide and redivide into paired beams and points. It also has large ears that are more like those of a mule than those of its more delicate cousin. Unfortunately people in different parts of Canada have given these two types of deer the same nickname, "jumper." In the Prairies the mule deer is dubbed "jumper," in recognition of its stiff-legged bouncing gait. Elsewhere people may mean the white-tail when they use the term, referring to that animal’s irregular jumping gallop when alarmed.