Description

The grizzly (Ursus arctos) is the second largest North American land carnivore, or meat-eater, and, like the larger polar bear, has a prominent hump over the shoulders formed by the muscles of its massive forelegs.

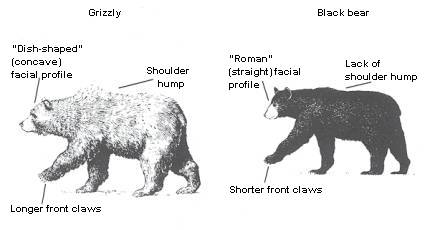

The Grizzly’s unique features are its somewhat dished face and its extremely long front claws (see sketch). Its colour ranges from nearly white or ivory yellow to black. Some are of uniform colour, but many Grizzlies have light or grizzled fur on the head and shoulders, a dark body, and sometimes darker feet and legs. The body shape and long fur tend to make Grizzlies look heavier than they actually are. Although Grizzly Bears have been known to weigh as much as 500 kg, the average male weighs 250 to 350 kg and the female about half that.

Grizzly Bear and Black Bear Comparison: The bear family includes seven species found in both the western and eastern hemispheres, and in South America. The brown bear Ursus arctos is one of the three species of bear found in North America. The other two are the polar bear Ursus maritimus and the black bear Ursus americanus. The Grizzly has certain unique characteristics, and at first scientists thought that it was a different species from the very similar European brown bear. But, in 1953, they assigned it to the same species as brown bears found in Europe and Asia.

Grizzly Bear and Black Bear Comparison: The bear family includes seven species found in both the western and eastern hemispheres, and in South America. The brown bear Ursus arctos is one of the three species of bear found in North America. The other two are the polar bear Ursus maritimus and the black bear Ursus americanus. The Grizzly has certain unique characteristics, and at first scientists thought that it was a different species from the very similar European brown bear. But, in 1953, they assigned it to the same species as brown bears found in Europe and Asia.

There are two recognized subspecies of the circumpolar brown bear Ursus arctos in North America. The Kodiak bear found on the Kodiak Islands of Alaska (Ursus arctos middendorffi) is one. All the rest, though they may differ in size because of geographic differences in the quantity and quality of food, are Grizzlies.

Signs and sounds

Grizzly Tracks

Habitat and Habits

The Grizzly is often considered a solitary animal, however scientists are learning more about the social life of grizzly bears and now see cases of group interaction among bears at certain times of the years. Its home range varies in size but usually is 200 to 600 km2 for females and 900 to 1 800 km2 for males. Generally, the more plentiful the food supply, the smaller the home range. However, the movements of adult males are also influenced by searches for receptive females during the breeding season. Females with newborn cubs have very small home ranges the first year following birth. Grizzly movements can be traced by attaching small transmitters to the animals, usually in a collar. These devices have shown that male Grizzlies sometimes travel as far as 250 km, as the crow flies, over the course of a year. They have also shown that bears that have been relocated after getting into conflicts with humans (usually associated with food attractants) can return from distances of more than 800 km to their capture site where they had previously been in conflict.

The nature of the terrain in a bear’s home range can significantly affect distribution. For example, in some mountainous regions, females with young, and independent subadults, mainly inhabit the rugged terrain of upper slopes and basins where adult males are not likely to travel. The latter tend to occupy valley bottoms of major drainages, travelling on the best trails and over the most accessible passes. Adult males are known to kill cubs and subadult bears; this is the reason why females and subadults endeavour to minimize contact with males.

The Grizzly has always been something of an enigma. A large body of folklore and tales has grown up around this much talked about and feared, but little understood, animal. The first white explorer to see Grizzly Bears and to record them in his journal was Henry Kelsey. On 20 August 1691, Kelsey mentioned seeing “a great sort of bear” near what is now The Pas, in west-central Manitoba. After their many dangerous encounters with individual Grizzlies, Lewis and Clark thoroughly described this animal in their journals of 1805. But not until the 1960s did extensive studies in Canada and the United States begin to make the Grizzly Bear and its habits better known.

Unique characteristics

The Grizzly matures late (reproducing at 5 years old) and produces young only every third or fourth year. Its size enables it to rule over our native wildlife without challenge from other animals. It has no natural enemies apart from people, except when young.

Unlike black bears, which have largely adapted to people and their activities, Grizzly Bears have not fared well in the face of civilization. While Grizzlies and humans coexist in many regions of the world, History shows us that there is a threshold of human interference beyond which Grizzlies just do not survive. Their keen sense of personal space and their occasional depredation of crops and livestock have brought this proud animal into conflict with people, inevitably to the Grizzlies’ detriment. Thus, their total range in North America has shrunk by more than half.

A Grizzly seldom looks for trouble. Its size allows it to avoid fights with other animals and, if at all possible, a Grizzly will avoid contact with people. The Grizzly is not as persistent around garbage dumps as the black bear, but occasionally its taste for garbage will give rise to trouble. They can also occasionally rip apart grain bins, eat standing crops, kill livestock and cause property damage. If surprised at close range, a Grizzly can ferociously defend itself, its young, and the food it is eating.

Range

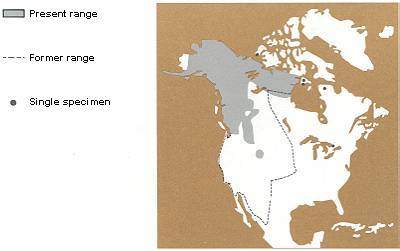

Historically the Grizzly was numerous south into California and Mexico and ranged across the western half of North America, approximately to the eastern boundary of Manitoba. As human populations have grown, the Grizzly’s range has gradually shrunk and is now limited to northwestern North America.

In 2012, estimated populations of Grizzly Bears were 691 in Alberta, 6 500 in British Columbia, 3 500 to 4 000 in the Northwest Territories, 6 000 to 7 000 in the Yukon, 1 530 to 2 000 in Nunavut, few in Manitoba, about 31 000 in Alaska, and 1 400 to 1 700 in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho.

Feeding

Although it is considered to be a meat-eater, the Grizzly is generally omnivorous—it eats a wide range of foods. Plants make up 80 to 90 percent of its diet. Grizzlies prey on mammals and migrating salmon, where they are available, but on the whole rely on vegetation as their primary food source.

On emerging from their dens in the spring, mountain Grizzlies tend to frequent avalanche slides and meadows where the vegetation is first exposed, and there they are often observed digging for roots of the legume Hedysarum. In fact, this root, rich in proteins, carbohydrates, and minerals, is perhaps the single most important food in much of the Grizzly Bear range. Not only is it widely consumed in April and May, but it is often used as a substitute for berries in late summer and autumn during years when berries are scarce.

As spring progresses into summer, hair-grass, horsetails, mountain sorrel, and other leafy plants form an important part of the bears’ diet.

For a brief time in spring, Grizzly Bears are significant predators of newborn elk, moose, deer, and caribou, but once these young animals are a few weeks old they are too nimble for a bear to catch. On rare occasions, Grizzlies can also kill full-grown elk, moose, deer, caribou, and cattle. Grizzly Bears have an excellent sense of smell and can locate a dead animal from tremendous distances. A Grizzly that finds this type of food generally remains nearby until it is completely gone or the bear is displaced from the site by a large more aggressive bears. As spring progresses into summer, hair-grass, horsetails, mountain sorrel, and other leafy plants form an important part of the bears’ diet.

Where they occur in sufficient quantities, grubs of insects and adult insects such as ants, ladybird beetles, and bees are eaten. During salmon migrations, coastal Grizzlies gorge themselves on fish. Similarly, Grizzly Bears that live on the Arctic tundra feed heavily on arctic ground squirrels in late summer.

Over most of the Grizzly Bear range, however, berries are a very important item in the bears’ diet. They are the food most often responsible for a bear attaining the fat deposits necessary for survival through the denning period. Some of the more important ones are buffalo berries, blueberries, huckleberries, cranberries, saskatoons, and crowberries.

Grizzly Bears will take advantage of food and garbage carelessly made available by people. Bears learn quickly and can become habitual visitors to campsites and dumps, if rewarded by the easy availability of food. Although such foods may be nutritious and plentiful, the practice often leads to a confrontation between bear and human, and the results can be tragic for both. Wildlife managers and the public should see that bears do not have access to our foods.

Breeding

Young Grizzlies are born in a winter den, usually during January and February. They are very small, weighing about 400 g and measuring less than 22.5 cm. The common litter size is two, but it can range from one to four. The young grow rapidly, and when they leave the den with the mother in spring they weigh about 8 kg. They continue gaining weight rapidly in the summer and enter the winter den approaching 45 kg. Usually they remain with the mother until June of their third year.

Grizzly Bears have a low reproductive rate. A female Grizzly does not have her first litter until she is five to seven years old, and she breeds at three- to four-year intervals. Female Grizzlies often bear no more than four or five litters in a lifetime. Age can be determined by the number of layers in the cementum rings in a bear’s tooth, a bit like counting growth rings in a tree trunk. Counting these layers—one layer appears for each year of the Grizzly’s life—has established that bears in the wild will live up to 31 years.

The Grizzly is less active after the breeding season and grows fatter on the abundant summer foods, which help it to survive the winter in its den. The pregnant females usually den first, entering around mid-November, depending on the weather and their body condition, with family groups denning shortly thereafter. Single bears den after the pregnant females. The adult males are likely to stay outside the den until late November or early December and emerge from it as early as March. The females, especially those with offspring, tend to stay in the dens until the young are fairly well grown in late April or early May.

Contrary to popular belief, Grizzlies are not true hibernators. True hibernation requires a significant drop in body temperature and respiration rate, whereas the Grizzly’s body temperature drops only a few degrees and its respiration rate is only slightly below normal. Also, true hibernating animals, such as ground squirrels, fall into a deep winter sleep, but Grizzlies, like black bears, do not. At most they are lethargic and can even be active all winter.

Conservation

In some jurisdictions, Grizzlies are hunted primarily as game animals throughout western Canada in both spring and fall. In addition, each year conservation officers capture or kill some as predators or when they become a threat to people.

On the whole, Grizzlies are not reliable hosts for parasites. Their few internal tapeworms and roundworms are mostly eliminated during the winter dormant period when the bear’s digestive system is inactive, and the animal usually carries only a few external fleas and ticks. Moreover, infections from wounds received either in hunting or fighting are rare, and the Grizzly living in the wild is relatively free of diseases.

While there are areas where Grizzlies and humans coexist, they tend to thrive mostly in relatively undisturbed areas. People are the biggest threat to the Grizzly. It suffers the greatest impact not from hunting, but from the continual increase of our population and the resulting erosion of Grizzly habitat. Only through better understanding of the Grizzly’s requirements and by seeking better ways to coexist can Canadians ensure that this bear will remain part of our living heritage and not just a picture in a book.

Resources

Online Resources

Species at Risk Registry. Grizzly Bear

Parks Canada, Bears in the Mountain National Parks

Canadian Geographic Kids, The Grizzly Bear

Print resources

Craighead, F., Jr. 1979. Track of the grizzly. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco.

Herrero, S. 1985. Bear attacks: Their causes and avoidance. Lyons and Burford, New York.

Murie, A. 1961. A naturalist in Alaska. Devin-Adair, New York.

Murie, A. 1981. The grizzlies of Mount Mckinley. U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

Russell, A. 1967. Grizzly country. Knopf, New York.

Schoonmaker, W.J. 1968. The world of the grizzly bear. Lippincott, Philadelphia.

Seton, E.T. 1929. Lives of game animals. Volume 2. Part 1. Doubleday, Garden City, New York.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1973, 1984, 1991, 2016. All rights reserved.

Text: K. Mundy

Revision: R.H. Russell, 1990; Gordon Stenhouse and Kyle Artelle, 2016