Description

The Canada lynx Lynx canadensis is a beautiful wild felid, or cat, of the boreal forest, or northernmost forest in the Northern Hemisphere. The lynx resembles a very large domestic cat. It has a short tail, long legs, large feet, and prominent ear tufts. Its winter coat is light grey and slightly mottled with long guard hairs; the underfur is brownish, and the ear tufts and tip of the tail are black. The summer coat is much shorter than the winter coat and has a definite reddish brown cast.

The Canada lynx Lynx canadensis is a beautiful wild felid, or cat, of the boreal forest, or northernmost forest in the Northern Hemisphere. The lynx resembles a very large domestic cat. It has a short tail, long legs, large feet, and prominent ear tufts. Its winter coat is light grey and slightly mottled with long guard hairs; the underfur is brownish, and the ear tufts and tip of the tail are black. The summer coat is much shorter than the winter coat and has a definite reddish brown cast.

Its large feet, which are covered during winter by a dense growth of coarse hair, help the lynx to travel over snow. The lynx, like the snowshoe hare, can spread its toes in soft snow, expanding its “snowshoes” still farther.

The lynx has large eyes and ears and depends on its acute sight and hearing when hunting. The lynx’s claws, like those of most other cats, are retractable and used primarily for seizing prey and fighting.

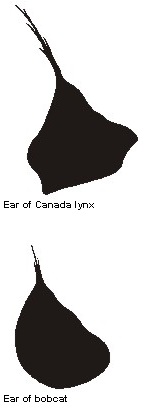

Of the three Canadian members of the cat family (Felidae)—the lynx, the bobcat, and the cougar—the lynx and the bobcat are most alike and are most closely related to each other. They probably both descended from the larger Eurasian lynx. There are small differences in appearance: on average, bobcats are slightly smaller; the bobcat’s feet are not as large as those of the lynx, making the bobcat less able to secure food in deep snow; the lynx’s tail has a solid black tip, whereas that of the bobcat has three or four narrow black bars and a black spot near the tip on its upper surface; and the bobcat’s fur has more pronounced spotting. The cougar is much larger and more powerful than either of them, and can be readily identified by its long tail.

Signs and sounds

The lynx has a variety of vocalizations, like those made by house cats, but louder.

Habitat and Habits

The lynx generally inhabits forested wilderness areas. It favours old growth boreal forests with a dense undercover of thickets and windfalls. However, this carnivore, or meat eater, will populate other types of habitat as long as they contain minimal forest cover and adequate numbers of prey, in particular snowshoe hares. Because hare populations increase in forests that are growing back after disruption by wildfires or logging operations, these regenerating forest ecosystems are often able to support denser populations of lynxes as well.

As long as they are not disturbed, lynxes are remarkably tolerant of human settlement. For example, since the early 1960s, they have occupied the partly cleared mixed-farming district near Rochester, in central Alberta. A few were shot in farmyards, but there was no intensive fur trapping, and lynxes remain in the area.

The size of the home range varies with numbers of lynxes and snowshoe hares in the area, available cover, and season. When there are fewer hares, each lynx needs a larger area on which to hunt. In summer, home ranges are larger than in winter. In Alberta, lynx tracked in winter had home ranges varying from 15 to 47 km2. On Cape Breton Island, a study that involved radio transmitters attached to adult lynxes measured home ranges of 12 to 19 km2 in winter and 27 to 32 km2 in summer. In Canada, scientists have measured daily travelling distances for lynxes ranging from less than a kilometre to 19 km.

The territoriality of these mammals is still poorly understood. Home ranges may overlap, especially where the lynx neighbours are of different ages and sexes. In general, the home ranges of adults do not seem to overlap with other adults of the same sex. The animals urinate frequently to mark their home range.

Periodically, there have been conspicuous mass movements of lynxes out of the boreal forest and onto the prairie grasslands. These were well known to early fur traders and trappers, but they ceased in 1925–26. During 1962–63, however, there was once again a notable movement out of the north. Lynxes entered large cities such as Edmonton, Calgary, and Winnipeg; appeared on the open grasslands of southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and North Dakota; and reached Iowa and southwestern Wisconsin. These same events were repeated during 1972–73. Like so many other aspects of the natural history of the lynx, these movements can be understood by relating them to the cyclical declines in populations of the snowshoe hare, the lynx’s main prey. Lynx populations that increase during periods of hare increase must either starve or emigrate when the hares disappear. The absence of any obvious movement between 1925–26 and 1962–63 probably reflected unusually low numbers of lynxes.

Like the cougar and the bobcat, the other two members of the cat family native to Canada, the Canada lynx tends to be secretive and most active at night and, like them, it is rarely seen in the wild. Even for trappers who have spent a lifetime in areas where lynxes are common, encounters with these predators are rare and memorable.

Unique characteristics

The lynx preys almost exclusively on the snowshoe hare. Since snowshoe hare populations follow a 10-year cycle, lynx numbers also fluctuate dramatically, building to a peak as hare populations increase, and then crashing. Scientists who have examined the fur-trading records of the Hudson’s Bay Company have been able to trace closely linked 10-year cycles of growth and decline in populations of the two species over the past 200 years. Figure 1 shows the cyclic fluctuations in the numbers of snowshoe hare and lynx pelts supplied to the company over a 90-year period.

Range

The range of the lynx is essentially that part of North America covered by boreal, or northernmost, forest and occupied also by the snowshoe hare. Between 1900 and the mid-1950s, lynxes became scarce in the southern portions of this range. This was probably due to trapping during periods of snowshoe hare scarcity (low years in the 10-year cycle). At these times lynx numbers are already low and fewer young are surviving to adulthood, so trapping can seriously deplete, or even eradicate, local populations. In the past 25 years, lynxes have reoccupied some of this southern range, and this may be due to tighter legal restrictions on trapping. The northern range expansion of the bobcat in the past century may also have contributed to the overall decline in lynx numbers. When both species compete for the same space and food resources, the lynx most often yields to the more aggressive and adaptable bobcat.

Feeding

More than 75 percent of the lynx’s diet in winter is snowshoe hares, and when they are abundant a lynx may kill one hare every one or two days. In summer the lynx’s diet is more varied. But even in summer hares remain the main prey, supplemented by grouse, voles, mice, squirrels, and foxes. A hungry lynx will devour an entire hare in one meal. It may also hide partially eaten prey to finish later. When it is available, lynxes will also supplement their diet with carrion, or dead flesh, from domestic livestock and/or big game animals, such as deer, but they rarely attack large prey. An exception occurs on the island of Newfoundland. After people introduced the snowshoe hare to the island in the 1870s, lynxes began to prey on caribou calves when snowshoe hares became scarce. In the 1960s, lynxes were killing so many calves that wildlife managers removed many of the lynxes found on the calving grounds. Today, the caribou population has increased to the point where lynx predation is not considered a threat.

Lynxes hunt at night. They watch and listen for prey, but they do not seem to track it by smell. Like all members of the cat family, they move silently. Although excellent climbers, they are seldom found in trees. Because they cannot run fast except over short distances, they stalk or ambush their prey at close range. A common strategy is to lie in wait beside the well-used trails, or runways, of the snowshoe hare. Success usually depends on whether the lynx manages to capture the hare at one bound—about 6.5 m or four hops for the hare.

Male lynxes hunt alone, except briefly during the mating season. By autumn, females travel with their kittens, the young learning to hunt, and the family group may stay together until the breeding season, in late February or March. Family groups cooperate to increase their hunting success. The mother and young often travel in single file through habitat where hares are scarce, but will travel abreast when hunting in habitat where hares are plentiful. A hare flushed, or forced out of its hiding place, by one lynx may be caught by another.

Breeding

Mating occurs during February or March each year, and the young (usually four) are born in April and May, 60 to 65 days later. Although the lynx seldom uses an underground den, young may be born under brush piles or uprooted trees, or in hollow logs, which provide shelter from rain and cold. The kittens, reared solely by the female, look like those of the domestic cat. Female kits may breed for the first time as they approach one year of age, but this depends on the abundance and availability of snowshoe hares and the physical and nutritional condition of the lynx.

Probably starvation following the rapid cyclic declines in snowshoe hare populations is the greatest single source of natural mortality among adult and yearling lynxes. About 40 percent of the total lynx population may starve to death following a crash in the snowshoe hare population. During the following three to four years, when the hare population is starting to rebuild, lynxes breed, but the kittens die before winter. This suggests that an adult female simply cannot support both herself and her litter when hares are scarce.

Conservation

In Canada, trapping seems to be the only important cause of death besides the decline of populations of the lynx’s main prey, the snowshoe hare. Although the wolf is alleged to be the chief natural enemy of the lynx in northern Europe, nothing is known of lynx–wolf interactions in North America. The incidence of diseases, such as rabies and distemper, among lynxes and their impact on populations are also unknown.

Trapping is also the most important influence of people on the lynx. The lynx is easily trapped, and when fur prices rise, trappers take a larger proportion of the lynx population. Intense trapping can remove most lynxes from a given area. Historically, trapping has caused long-term changes in the size of the lynx population in Canada. Lynx populations began to decline after 1900, and the decline continued to the mid-1950s. At that time, garments made of long-haired furs went out of fashion, there was a major depression in fur prices and a decline in trapping, and the lynx population was able to recover. Since the early 1970s, the demand for lynx pelts has risen steadily. The average price paid per pelt went from about $30 in 1970 to peak in the mid-1980s at over $500 per pelt. By 1990, it had fallen to $117.

Today, the lynx is trapped in all provinces and territories except Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. Trapping is confined to regulated seasons, and wildlife managers can vary the regulations as needed from year to year and among districts within a province. Many jurisdictions have also placed restrictions on the number of lynxes that may be killed. Some biologists have recommended closing trapping seasons entirely during lows in the population cycle. Several provinces are carefully studying the influence of trapping on their lynx populations and adjusting regulations to protect this renewable resource. High fur prices have also stimulated interest in raising lynxes on ranches. It is possible that ranching may one day provide a considerable number of the pelts that enter trade, as is now the case with mink and fox.

In general, human activities do not seem to be threatening lynx populations. Although the lynx is usually considered to be a wilderness animal, human settlement does not seem to have reduced its range. Logging in the boreal forest that results in a good mix of mature conifer stands (for cover and travel) and regenerating stands (in which snowshoe hares abound) may even enhance habitat for lynx. Forestry operations, however, provide roads and ease of access to the trapper. If the regulations governing logging are not conservative and flexible enough, extensive clearcutting that results in the virtually complete removal of conifer forests from large tracts of land is probably harmful to resident lynx populations.

Resources

Online Resources

Parks Canada, Banff National Park, Canada Lynx

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Canada Lynx

Print resources

Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Brand, C.L., and L.B. Keith. 1979. Lynx demography during a snowshoe hare decline in Alberta. Journal of Wildlife Management 43:827–849.

Elton, C., and M. Nicholson. 1942. The ten-year cycle in numbers of the lynx in Canada. Journal of Animal Ecology 11:215–244.

MacLulich, D.A. 1937. Fluctuations in the numbers of the varying hare (Lepus americanus). University of Toronto Studies Biological Series 43. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Parker, G.R., J.W. Maxwell, L.D. Morton, and G.E.J. Smith. 1983. The ecology of the lynx on Cape Breton Island. Canadian Journal of Zoology 61(4):770–786.

Quinn, W.S., and G.R. Parker. 1987. Lynx. In M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, editors. Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Toronto.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1977, 1988, 1993. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/59-1992E

ISBN 0-662-19412-8

Text: L.B. Keith

Photo: Tom W. Hall