Description

Stinkpot

Freshwater turtles are reptiles, like snakes, crocodilians and lizards. Like other reptiles, they are ectothermic, or “cold-blooded”, meaning that their internal temperature matches that of their surroundings. They also have a scaly skin, enabling them, as opposed to most amphibians, to live outside of water. Also like many reptile species, turtles lay eggs (they are oviparous). But what makes them different to other reptiles is that turtles have a shell. This shell, composed of a carapace in the back and a plastron on the belly, is made of bony plates. These bones are covered by horny scutes made of keratin (like human fingernails) or leathery skin, depending on the species. All Canadian freshwater turtles can retreat in their shells and hide their entire body except the Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). This shell is considered perhaps the most efficient form of armour in the animal kingdom, as adult turtles are very likely to survive from one year to the next. Indeed, turtles have an impressively long life for such small animals. For example, the Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingi) can live for more than 70 years! Most other species can live for more than 20 years.

There are about 320 species of turtles throughout the world, inhabiting a great variety of terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems on every continent except Antarctica and its waters. In Canada, eight native species of freshwater turtles (and four species of marine turtles) can be observed. Another species, the Pacific Pond Turtle (Clemmys marmorata), is now Extirpated, having disappeared from its Canadian range. Also, the Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) has either such a small population that it is nearly Extirpated, or the few individuals found in Canada are actually pets released in the wild. More research is needed to know if these turtles are still native individuals. Finally, the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), has been introduced to Canada as released pets and, thus, is not a native species.

Blanding’s Turtle

Our freshwater turtles come in a variety of shapes, colours and sizes. In some species, adult males are smaller than adult females, or the reverse, but most species show very little sexual dimorphism, so males and females are almost identical. Typically, freshwater turtles are smaller than their marine counterparts and their looks are more varied. They have adapted and are specialized to live in a great variety of habitats, and so can look quite different from one species to the next. Two of our most distinctive-looking turtles are probably the Common Snapping Turtle – and the Spiny Softshell (Trionyx spiniferus). While these two species are the largest freshwater turtles in Canada, they have very different looks. The softshell is primarily aquatic, making its flat, soft shell necessary for hiding in the mud at the bottom of the water. Also, its long neck and pointy snout makes it easier to breathe while staying almost completely underwater. The prehistoric-looking Snapping Turtle is also mostly aquatic, but the fact that it cannot withdraw in its shell and its diet has given this species a long neck and very strong jaw to defend itself and forage.

Habitat and Habits

Spiny Softshell

Freshwater turtles are active, in Canada, from April to October. Turtles become active in the spring when water and air temperatures go above 15 to 20°C. Spotted Turtles are among the first freshwater turtles to become active in the spring. During its activity period, a typical freshwater turtle’s day is divided between resting, basking and foraging. Basking is the behaviour that turtles, and other reptiles, exhibit when they are resting in the sun, either out of the water or just at the surface. This helps regulate their bodies’ temperature (as they are ectothermic), is beneficial to their skin and shells, and speeds up their metabolism. While most turtles are diurnal (active during the day), the Common Snapping Turtle and the Eastern Musk Turtle (Sternotherus odoratus), or Stinkpot, may be looking for food during the night.

Freshwater turtles can be found in a great variety of habitats, including most wetlands (even inhospitable bogs!), lakes and rivers. Still, most prefer shallow waters and slow currents, with soft mud at the bottom and aquatic vegetation where they can hide. One exception is the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta), which prefers hard substrate and clear waters. Not all freshwater turtles are good swimmers, so a substrate on which they can walk at the bottom of the water, is a necessary element for some species.

But even if they are recognized as aquatic animals, all freshwater turtles rely on land for their survival. Indeed, they all need to come out of water for greater or lesser periods of time, depending on the species. Some only come on land to lay their eggs and remain in water for the rest of the year. This is the case for the Eastern Musk Turtle and the Common Snapping Turtle. The Spiny Softshell, which is also well adapted to aquatic life, can even absorb oxygen dissolved in the water through its skin! Others, like the Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) and the Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica), will come out on logs or rocks daily in the summertime to bask. But some species, even if they do still need access to water for periods of their life cycle, can spend a larger period of their time on land. This is the case of the Wood Turtle, which inhabits woodlands, farmlands and grasslands not too far from water for much of its activity period. This species is considered the most terrestrial of our turtles, but the Blanding’s Turtle and the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) may also be observed wandering out of the water, close to the shoreline, especially in the spring. The Blanding’s turtle may even travel long distances on land to go from a wetland to another, or to reach their nesting site.

Map Turtle Basking

In or out of the water, adult freshwater turtles do have a few predators, like birds, mammals and other turtles. Other than their shells, some species have developed defense mechanisms to protect themselves. For example, basking turtles that are startled will quickly jump in the water, alerting other individuals to do the same. The Common Snapping Turtle’s powerful jaw and claws are also great features to deter any possible predator. The reason why the Eastern Musk Turtle is also called Stinkpot is that it can release a foul-smelling liquid to discourage possible attackers.

During the winter, when temperatures get too cold to sustain their metabolisms, all freshwater turtles head underwater to hibernate. They typically bury themselves in the substrate, or the sand, mud or pebbles found at the bottom of their aquatic habitat, under the ice, as they cannot survive being completely frozen. They remain dormant, slowing their metabolism down in order to conserve energy and use as little oxygen as possible. The Common Snapping Turtle can survive the winter months completely covered in mud with very little available oxygen in the water.

Range

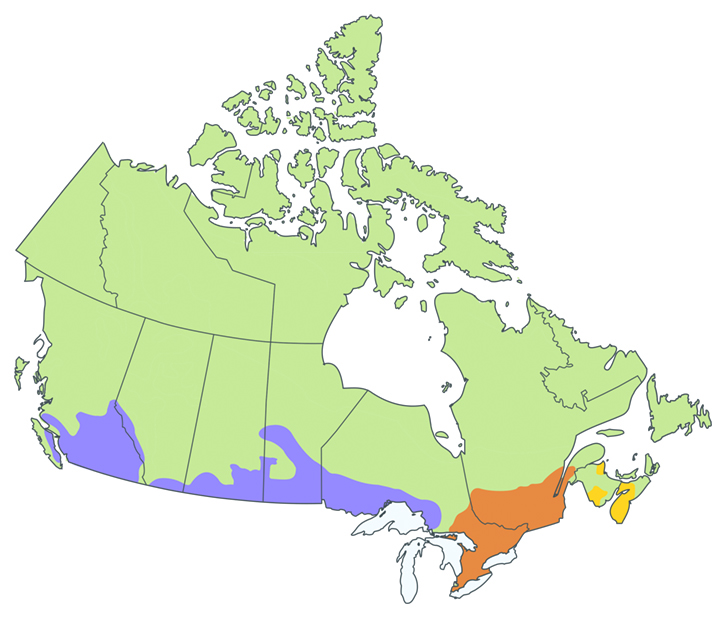

Freshwater turtles occur in every Canadian province except Newfoundland and Labrador. They are absent from every territory, since the winters are too long for these reptiles to thrive. Most species are restricted to southern Ontario (where all species can be observed) and Québec, while two others can also be found in the Maritimes or in southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Only one species can be found from coast to coast, the Painted Turtle. It has widest distribution in Canada. Its eastern subspecies is found in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, its midland subspecies, in southern Ontario and Québec, and its western subspecies, in central and western Ontario all the way to British Columbia.

Distribution of the Painted Turtle in Canada. The purple area shows the distribution of the Western subspecies, the orange, the Midlands subspecies, and the yellow, the Eastern subspecies. ©Wild About Turtles, Canadian Wildlife Federation

Feeding

Snapping Turtle

Unlike most other reptiles, turtles do not have teeth. They rely on their powerful jaws, strong horny beaks and front claws to seize and tear apart their food. If the morsels are small enough, they may swallow them whole, but if not, they will chew them with their beaks and jaws. Our freshwater turtles are omnivorous: they eat both plant and animal material, in different ratios according to the species or the age of the individuals. Globally, a turtle’s diet includes aquatic and terrestrial plants, invertebrates like snails, slugs, earthworms, crayfish and insects, and even vertebrates like fish, amphibians and other turtles in some cases. Some consume more plant material, like the Wood Turtle, while others have a more carnivorous diet, like the Common Snapping Turtle, which mostly scavenges for dead prey. Most freshwater turtles forage only underwater, lying in ambush in the mud waiting or actively seeking a prey. Others, like the Blanding’s Turtle and the Wood Turtle, are able to catch food on land as well. Indeed, the Wood Turtle is thought by some to trample their feet on the ground, emulating the sound of rainfall, to get earthworms to come out of the ground and catch them.

Breeding

Snapping Turtle Hatchling

Breeding begins at sexual maturity, when the turtles are between 10 and 20 years old, depending on the species. This process starts as soon as spring arrives, and the courtship between males and females can happen at any time until the fall. Mating occurs underwater, and the eggs contained within the females are then fertilized. In some species, females can store sperm from a given male to fertilize later clutches, sometimes years after the fact! Females of several freshwater turtle species have also been known to be able to produce clutches fathered by several different males at the same time.

When they are ready to lay their eggs, females dig their nests in the sand or the earth near their aquatic habitats. Between five (for the Spotted Turtle) and 100 (for the Common Snapping Turtle) eggs are then laid, and are often covered by the female using her hind legs. Except for the Wood Turtle and the Spiny Softshell, it’s the temperature in the nest, during the incubation, which conditions whether a hatchling will be male or female. Higher temperatures will cause for more females to be born, and lower incubation temperatures, more males.

The female leaves the nest after having laid the eggs and the hatchlings are born with no parental care. Following their birth, the hatchlings from most species will instinctively go to the water, where they can more easily hide from predators. Painted Turtle and the Map Turtle hatchlings may be born in the fall, which means that these hatchlings remain in the nest until the following spring. They can survive throughout the winter at temperatures as low as -10°C with the help of antifreeze chemicals which they produce in order for their cells to remain unfrozen and undamaged. They can only do so during their first winter, following which they must head to the water.

Even if several clutches, or batches of eggs, may be laid every year by the same female, very few hatchlings survive to adulthood. Nest predation is very common, birds and mammals will often eat all the eggs once the female has left, or sometimes when she is still present! This is thought to be why turtles are such long-lived species, since it may take them many years to produce one offspring that will survive until adulthood. Hatchlings that do survive will grow rapidly until they are mature, and if the conditions are good, individuals from some species may continue to grow their whole life.

Conservation

Spotted Turtle

Turtles have been on Earth for over 200 million years, surviving major events like the extinction of dinosaurs, numerous ice ages and others. Today, our freshwater turtles face a new challenge: human activity. The fact that freshwater turtles need both terrestrial and aquatic habitats to survive makes their conservation relatively complex, since many types of habitats need to be protected for a single species. The need for several types of habitats throughout the year also increases the amount of threats affecting them, since different elements can threaten them in each habitat.

Unfortunately, freshwater turtles are indeed having a hard time. Every species in Canada is either at-risk, or has a population or subspecies that is at-risk.

Table 1 At-risk native turtle species in Canada, according to the Species at Risk Act.

SARA Status

| Common Snapping Turtle | Special concern |

| Eastern Musk Turtle | Special Concern |

| Western Painted Turtle Pacific Coast population |

Endangered |

| Western Painted Turtle Intermountain – Rocky Mountain population |

Special Concern |

| Map Turtle Northern subspecies | Special Concern |

| Blanding’s Turtle Nova Scotia population |

Endangered |

| Blanding’s Turtle Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population |

Threatened |

| Wood Turtle | Threatened |

| Spotted Turtle | Endangered |

| Spiny Softshell | Threatened |

Map Turtles

There are many threats that our freshwater turtles face. Degradation, fragmentation and loss of their aquatic and terrestrial habitats are the biggest threats, along with invasive alien species (like the Red-eared Slider, in some areas, or invasive water plants), pollution, the spread of diseases and drought-causing climate change have all contributed to the decline in turtle populations. Other threats include human disturbance, like boat traffic (which cause collisions or injuries with propellers), motor vehicle collisions, accidental capture in fishing gear and illegal collection for the pet trade.

But even without the threats mentioned above, in pristine, protected habitat, research in Ontario has shown that virtually all turtle nests were being destroyed within 48 hours of being laid. The culprit? Natural predators, such as raccoons and skunks, whose populations have increased because of the proximity of humans, which provide extra food sources. These mammals prey on eggs and hatchlings which are easy targets. This explains why Ontario’s turtle populations, in both urban and rural areas, consist primarily of adults, as too few hatchlings survive to adulthood.

So what is being done to help our freshwater turtles out? Species at Risk that are listed as Threatened and Endangered and their residences are protected by the Species at Risk Act, and in the case of species of Special Concern, management plans are created to help them recover. This also means that more research is being done to find out all that we can about them in order to better conserve them. In many areas, scientists work alongside volunteers to monitor populations of at-risk turtles. Some individuals can also be tagged with radio-transmitters, enabling us to follow them around and to collect valuable data about the turtle’s movement patterns and habitat use. This data also helps us to know exactly how a population is doing, and how it’s reacting to changes in its environment. If the number of young individuals is found to be too low, scientists may try to protect the nests and eggs by putting cages around them. These cages enable hatchlings to get out, while preventing predators to get in. Another method is to collect the eggs and incubate them in an artificial incubator in a lab, and then to release them at the nesting site when they have hatched. These methods might help increase population numbers in the long run.

Other research includes trying to find out how fishery methods can be changed to prevent accidental turtle by-catch by fishing gear, and examining the genetic diversity of some populations to see how it can withstand changes in their habitat.

What we can do

- If you see a turtle crossing sign while driving, slow down and keep an eye out turtles on the road!

Snapping Turtle Crossing the Road

- Learn how to handle turtles if you live in an area where they are prevalent, so that you are ready to act if you see a turtle crossing the road. If you need to move a turtle, move it safely to the side it was already heading towards

- Report your sightings of turtles to your provincial atlas, as what you have seen may be useful to researchers

- Participate in a shoreline clean-up to help the turtles’ habitats become free of garbage (but leave dead trees and branches, as they may be good basking spots!)

- See if there are turtle research projects in your area that could need volunteers to help, and if there are, participate!

- If you see a turtle that seems safe, please observe it from afar, as disturbing it could cause it stress

- Talk turtles! Share your love for Canada’s turtles with friends and family. Let them know why protecting turtles and their habitat is important to you. The more people know about turtles, the better!

Resources

Blanding’s Turtle

Explore the biology of freshwater reptiles found in Canada!

Ontario Reptile and Amphibian Atlas Program

Canadian Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Network

CWF’s Wild About Turtles poster

Printed Resources

Turtles of the United States and Canada

Carl H. Ernst, Jeffrey E. Lovich

Hopkins Fulfillment Service; 2 edition (May 12 2009)

Scientific Reviewers

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Patrick Paré

Biologiste, M.Sc.

Directeur, Recherche et Conservation

Zoo de Granby

Yohann Dubois

Biologiste, M.Sc.

Direction générale de l’expertise sur la faune et ses habitats

Secteur de la faune

Ministère du Développement durable, de l’Environnement, de la Faune et des Parcs

Gouvernement du Québec

Melissa Lefebvre

Education Specialist

Canadian Wildlife Federation

Jean-François Déry

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Marie-France Gravel

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved.

Text: Annie Langlois