Description

The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is a fascinating migratory fish with a very complex life cycle. Like salmon, it lives both in freshwater and saltwater. But its life-cycle is exactly the reverse of salmon’s: the eel is a catadromous species. It is born in saltwater and migrating to freshwater to grow and mature before returning to saltwater to spawn and die. The American Eel can live as long as 50 years.

It is a long, slender fish that can grow longer than one metre in length and 7.5 kilograms in weight. Males tend to be smaller than females, reaching a size of about 0.4 m. With its small pectoral fins right behind its gills, absence of pelvic fins, long dorsal and ventral fins and the thin coat of mucus on its tiny scales, the adult eel slightly resembles a slimy snake but are in fact true fish. Adult eels vary in coloration, from olive green and brown to greenish-yellow, with a light gray or white belly. Females are lighter in colour than males. Large females turn dark grey or silver when they mature.

It is known by a variety of names in Canada, including: the Atlantic Eel, the Common Eel, the Silver Eel, the Yellow Eel, the Bronze Eel and Easgann in Irish Gaelic. In Indigenous languages, like Mi’kmaq, it is known as k’at or g’at, the Algonquins call it pimzi or pimizì, in Ojibwe bimizi, in Cree Kinebikoinkosew and the Seneca call it goda:noh.

The American Eel is the only representative of its genus (or group of related species) in North America, but it does have a close relative which shares the same spawning area: the European Eel. Both have similar lifecycles but different distributions in freshwater systems except in Iceland, where both (and hybrids of both species) can be found.

Habitat and Habits

Credit: Ronald C. Philips PhD Credit: Ronald C. Philips PhD |

| Eelgrass |

Throughout its lifecycle, the American Eel will use a wide variety of habitats. In fact, it’s thought to occupy the broadest range of habitats of any fish in the world! While a majority of eels spend most of their lives in freshwater lakes and rivers, some remain in salt or brackish water (where salt and freshwater mix) close to the coast.

During the winter, in saltwater or brackish water, eels will find shelter in the mud at the bottom of estuaries and bays, but we don’t know much about the eels’ habitat in freshwater during the cold season. Some eels have been found to spend the winter in depths greater than 10 m. Previously, eels were only thought to overwinter in shallow bays. When the water temperature goes below 5 °C, eels burrow in the substrate and go into state of torpor, or complete inactivity.

When it’s spawning, every single American Eel, whether it migrated to live in freshwater or not, travels offshore to a specific area of the Atlantic Ocean called the Sargasso Sea. This calm, warm-water area is created by circulating ocean currents creating a gyre where seaweeds float at the surface.

The American Eel can become prey to other fish and birds at any point of its life-cycle, in either fresh or saltwater. During the day and when the eels are younger (and therefore smaller), eels will use the substrate (rock, sand and mud), rock piles and woody debris (like logs and snags) at the bottom of the water, or aquatic vegetation, to hide from predators. Eels regularly burrow into sand and mud to hide completely. In saltwater or brackish areas, the eel can be found in shallow, protected waters of the continental shelf, sometimes in areas with eelgrass beds.

Range

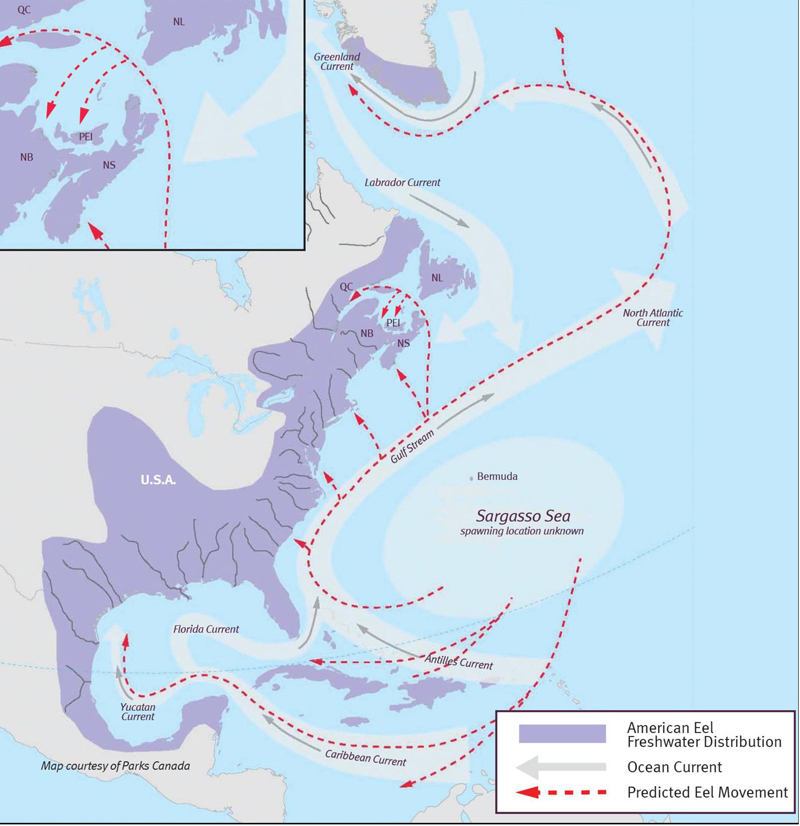

Credit: Parks Canada / Parcs Canada Credit: Parks Canada / Parcs Canada |

| Distribution of the American Eel |

The American Eel spawns exclusively in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the south of the North Atlantic Ocean. They migrate to coastal and inland areas as they grow.

While some individuals remain in brackish or coastal saltwater systems close to shore their whole lives, the American Eel is mostly found in inland freshwater habitats with some connection to saltwater. Historically, this included, all accessible freshwater habitats, estuaries, and coastal marine waters in Canada that were connected to the Atlantic Ocean up to the mid-Labrador coast. It has been found inland in the St. Lawrence watershed to the Great Lakes, stopping at Niagara Falls (although it is possible that eels were once found further in the Great Lakes basin). The density of eels within an area tends to decrease as it gets further from the ocean, as less and less eels migrate all the way upstream. Interestingly, only females have been found inland in Ontario and western Québec, and these are the largest and most fertile in the world.

Closer to the Atlantic, smaller male and female eels seem to live in mixed-sex populations. Scientists think that this is linked to the eels’ genetics and perhaps to natural selection processes.

Internationally, its freshwater distribution ranges from West Greenland and Iceland in the North to Panama and even Brazil in the South.

Feeding

An eel’s diet will vary quite a bit as they grow and mature. In its earliest stage, as a larva, it consumes particles out of the water column. As it grows older, throughout its migration, it starts feeding on the small larvæ of insects or other invertebrates. When it reaches its main habitat, where it spends most of its life, an American Eel becomes a nocturnal omnivore, hunting at night for fish, molluscs, crustaceans, aquatic insect larvae, surface-dwelling insects, worms and plants. For much of its life, crayfish are its preferred prey. It generally chooses small prey which can be easily attacked and it is considered a top predator in the food chain. It stops feeding during the winter, and once it becomes sexually mature and is ready to migrate back to the ocean.

Breeding

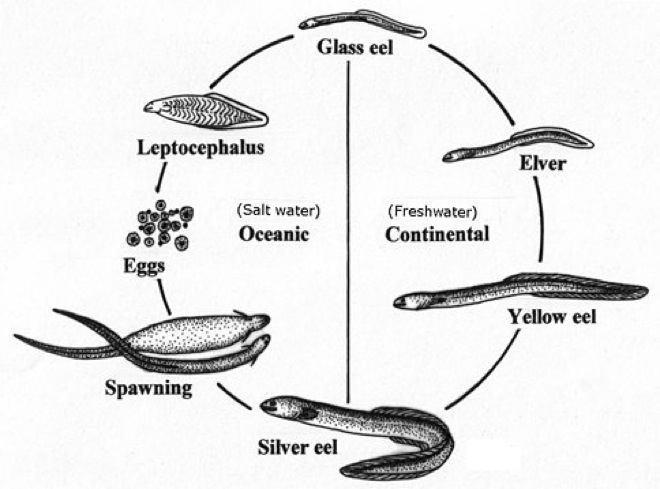

Credit: Ministry of Natural Resources of Ontario Credit: Ministry of Natural Resources of Ontario |

| Life cycle of the American Eel |

An American Eel’s complex life starts and ends in the Sargasso Sea. In late spring to late fall, Canadian sexually mature eels will start their migration to the open ocean in order to spawn — a 5,500 kilometre journey. An individual spawns, or reproduces, only once in its lifetime, and spawning happens from late winter to early spring in the Sargasso Sea. Females can lay as many as 22 million eggs, however they normally lay between 0.5 and four million eggs. Scientists have discovered that larger female eels, like the ones found furthest inland in Canada, are often more fertile, making them very important for the next generation. The male eel will fertilize the eggs once they are laid. Out of the millions of eggs laid and fertilized, only a small percentage will survive for the next stage of their lifecycle.

After about a week, the surviving fertilized eggs hatch and eel larvæ are born. These larvæ are called leptocephali. They are transparent and are shaped like a willow leaf. These larvae will leave the Sargasso Sea, passively drifting (not actively swimming) in the Gulf Stream, a major ocean current, for seven to 12 months. They transform into glass eels once they reach 55 to 65 milimetres in length, as they approach the shallower ocean waters of the continental shelf. Glass eels look like adult eels but are much smaller and are clear and transparent. As they move closer to the shoreline, they gradually become darker, move from the water column to the bottom substrate, and become elvers.

For three months to a few years, elvers will migrate to areas closer to shore or up rivers systems. When they reach their destination, they become immature eels, or yellow eels. As their name implies, they are yellowish and cream in colour. The yellow eels remaining in brackish water or saltwater will go through their lifecycle much quicker (about nine years) than the ones migrating further inland to freshwater habitats (up to 50 years). It’s during that phase of their lives that most of their growth happens, and that male and female eels become different: females become larger and lighter-coloured. When they become sexually mature, or adult eels, they are called silver eels. At this stage, they are ready to migrate back to the Sargasso Sea by physically changing in order to conserve energy for the long swim back to where they were born. When they arrive, they will spawn and die. Scientists have found no eels that have spawned and then made it back to freshwater.

Conservation

The American Eel is considered an indicator species: the health of its populations is a good indicator of the integrity of an ecosystem or habitat. If the eels are doing well, the whole habitat is likely doing well too. But some populations aren’t thriving, sadly, and have been declining dramatically over the last century. Because of this, the species was assessed as Threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2012. It currently has no status under the federal Species at Risk Act, so it is not legally a species at risk in Canada, but it does have different statuses in some provinces, including Ontario, where it was listed as Endangered and became protected under the Ontario Endangered Species Act.

The threats causing this decline both inland and in coastal Canada include changes to the eel’s habitat, the presence of several dams and turbines on rivers, the historical fishery harvest of the species, the presence of contaminants and pollutants in the water and an exotic parasite which may cause health issues.

It’s further inland that the decline is sharpest, as dams and turbines are especially problematic for eels. These structures become major barriers to their migration in the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa rivers, for example. In some areas, as much as 98.8 per cent of the historic population has vanished. Populations that live closer to the ocean tend to fare better as there are fewer obstacles to their migration.

In its spawning range, in the Sargasso Sea, and during its migration, threats include changes to ocean conditions related to climate change and pollution.

Credit: Algonquians of Ontario Credit: Algonquians of Ontario |

| American Eel report from the Algonquins of Ontario |

Scientists still have much to discover about the eel, but there are many ongoing projects to help fill those knowledge gaps. Recently, Canadian scientists studied eel genetics which gave very important information for conservation. Given that some juvenile eels have been found upstream from dams, scientists need to know how they managed to bypass major obstacles. Some eels were taken from an eel ladder on the St. Lawrence River and transferred upstream in the Ottawa River. The Canadian Wildlife Federation tagged some with acoustic transmitters so that scientists could follow their path. This will help us to discover the best places to install fish ladders, an installation that would help eels bypass dams. In other areas, negotiations between government, conservation organizations and hydropower companies in Ontario and Québec have led to the development of action plans to try and reduce dam-related mortalities with the installation of fish ladders and passages. Other solutions that are in place at the government level is the closing of the once very productive eel fisheries in Ontario and the reduction of the number of eels caught by 50 per cent in Québec.

Scientists and governments are also working with Indigenous groups in order to get more information about the eels. This is called aboriginal traditional knowledge, or ATK. Getting more data on the historical range and habits of the eels through ATK provides vital information about the eels themselves as well as where and how we should focus our conservation efforts. Local clubs, stewardship councils and organizations are also very active in eel conservation. They help by monitoring, conducting inventories and studying their local eel population.

The American Eel was not only once an important fishery in some areas of eastern Canada, it was of foremost importance to some Indigenous peoples. It is sacred to the Algonquin people, having been part of their culture for thousands of years as the formerly most abundant species in the Ottawa River watershed. They see the eel as a provider of nourishment, medicine and spiritual inspiration. But the conservation of the American Eel is not only important to humans, it is vital to a variety of birds, fish and mammals as this fish plays an important role in Canada’s aquatic biodiversity and ecosystems.

What we can do

You can also help the American Eel by getting in touch with a local organization which aims at protecting your watershed or river to participate in their activities and citizen science initiatives. If you find or accidentally catch an eel, dead or alive, you should report it to your local natural resources office. This will provide very important data about eel populations to scientists!

Resources

IUCN Redlist, The American Eel

Species at Risk Registry, The American Eel

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, The American Eel

Algonquins of Ontario, Returning Kichisippi Pimisi, the American Eel, to the Ottawa River

Ottawa Riverkeeper, the American Eel

Text by Annie Langlois, MSc Biology

Reviewed by:

Nicolas Lapointe, PhD

Senior Conservation Biologist – Freshwater Ecology, Canadian Wildlife Federation

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2017. All rights reserved.