Description

The Bufflehead Bucephala albeola is Canada’s smallest diving duck. Strikingly patterned in black and white, and constantly active, it attracts attention out of proportion to its relatively small numbers.

Buffleheads are compactly built birds, with males, or drakes, averaging 450 g in weight and females about 340 g. During their migrations they are much heavier, with up to 115 g of stored fat as fuel for their travels. Hunters sometimes call these fat birds “butterballs.”

Adult males are black above and white below, with bright pink feet. They wear a white “shawl” around the back of the head, and a broad white band extends from front to back across each wing. The females and first-year males are more drab, with the dark areas sooty-grey or brownish rather than black, and the white areas duller and smaller in size than in adult males. Like their near relatives, the goldeneyes and mergansers, Bufflehead males do not attain adult plumage until their second winter, and first breed when nearly two years old.

Signs and sounds

Both sexes are normally silent, and the only sound commonly heard from Buffleheads is the grrk call of females when alarmed near the nest or brood.

Habitat and Habits

Buffleheads are constantly active, all their movements being energetic and abrupt. They seldom rest on the water in flocks as do the Aythya diving ducks (scaup, Redhead, Canvasback). Buffleheads alternate periods of feeding with preening bouts or courtship displays.

In winter Buffleheads frequent the shallow, sheltered waters of coves, river mouths, and lagoons, which have a muddy or gravelly bottom, and they often feed around old wharves or log booms. Buffleheads are seldom found along exposed shores at any season. Their breeding habitat is small ponds, usually in wooded areas. Unlike other related species, they seldom nest by rivers and larger lakes, possibly because these waters are inhabited by northern pike, a large fish that often feeds on small ducklings.

Buffleheads are not gregarious, or sociable, and typically occur in groups of 10 or fewer birds. When both sexes are present, displays are frequent, but females do not respond to displays by first-year drakes.

Unique characteristics

The males often try to drive away other drakes displaying at the same female, either by rushing over the surface or by diving and coming up under the intruder. The vigorous splashing that results is visible at a considerable distance. Even when too far away to be recognized by appearance, Buffleheads can often be identified by this splashing.

Range

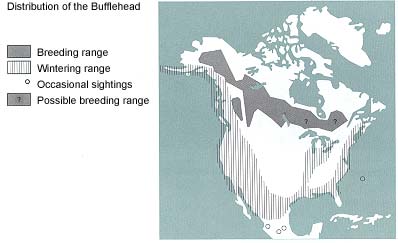

Buffleheads occur from coast to coast, though they are seldom numerous. In spring and summer, most breed in British Columbia east of the coast ranges and in the northern half of Alberta, although small numbers occur east to Ontario or even Quebec, and north to the southern parts of Alaska, Yukon, and Mackenzie. In winter, they are common on Canada’s west coast and regular in favoured spots around Lake Ontario and the southern coasts of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. However, the majority winter in the United States, from New Jersey to North Carolina in the east, and from Washington to central California in the west.

Buffleheads occur from coast to coast, though they are seldom numerous. In spring and summer, most breed in British Columbia east of the coast ranges and in the northern half of Alberta, although small numbers occur east to Ontario or even Quebec, and north to the southern parts of Alaska, Yukon, and Mackenzie. In winter, they are common on Canada’s west coast and regular in favoured spots around Lake Ontario and the southern coasts of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. However, the majority winter in the United States, from New Jersey to North Carolina in the east, and from Washington to central California in the west.

They migrate south late in fall, first appearing in settled parts of Canada in late October and early November. Birds from British Columbia and the Peace River district of Alberta move directly to the Pacific, crossing the mountains at high altitudes. Those from central Alberta move south over the mountains of ldaho and Utah to the scattered reservoirs of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and southern California. But the greatest numbers move east and southeast across the prairies towards the Atlantic. The main stopover areas include Minnesota and Wisconsin, Lake Erie, and the Atlantic coast, these areas being about 800 km apart, a distance that ducks flying at 55 to 65 km per hour could cover in one night.

Although Buffleheads banded in Alberta have been shot in 36 states and five provinces, none has yet been recovered in Saskatchewan and only one in Montana, which suggests that they cross these areas in a single flight. A few turn south to winter in the Mississippi and Tennessee valleys or on the Gulf coast, but most continue east to the Atlantic. In spring, a few appear in the northern states or southern Ontario in March, but the main movement is during the latter half of April. The spring migration, as with most ducks, is more prolonged than the fall migration, since the birds must wait for more northern water areas to become ice-free. In British Columbia the first movement to the interior is largely made up of unpaired adult males, but this does not seem to be true elsewhere.

Feeding

Feeding is always by diving, even in shallow water, the dives being longer in deeper areas as most food is picked from the bottom. The Buffleheads’ main foods are arthropods, mostly insect larvae in fresh water and small crustaceans, such as shrimps, crabs, amphipods, in salt water. In fall they eat many seeds of aquatic plants, and in winter they take small marine snails or freshwater clams in their respective habitats.

Breeding

Courtship occurs through the winter, becoming more intensive as spring approaches, but most pairing seems to take place during the spring migration, and the birds are paired by the time they reach breeding areas. As with most diving ducks, males outnumber females, so a fair proportion of adult males remains unpaired.

Courtship is characterized by rapid, jerky movements, most frequently a head-bobbing action by the drake. The most striking display is a short flight over the female in which the male flutters its wings below the level of its body, keeping the head and tail lowered, finally landing in a “water-skiing” posture that displays the feet as well as the plumage. The upwards stretch with wing-flapping, common to most ducks and some other water birds, terminates most bouts of displaying.

In most areas Buffleheads start nesting soon after their arrival. The female lays her eggs in a tree cavity, usually the former nest of a Flicker (woodpecker). The related goldeneyes and mergansers are also tree-nesters, and some people refer to any duck nesting in a tree as a “wood duck.” The true Wood Duck, however, is a more southern species and is not at all closely related to the tree-nesting diving ducks. The Bufflehead is the only tree-nesting duck that can use nest holes of Flickers since the other ducks need larger cavities.

The clutch, or set of eggs, is typically 7 to 11, though occasionally as few as 5 or as many as 14. Sometimes more than one female lays in a single nest, leading to sets of 15 or even 20 eggs. Such “dump nests,” which may be deserted without being incubated, are less frequent with Buffleheads than the larger ducks, which have more difficulty in finding nest sites. The eggs are usually laid at intervals averaging more than 24 hours. Incubation, or keeping the eggs warm until they hatch, lasts about 30 days, and the hatch occurs in mid to late June. The ducklings remain in the nest 24 to 36 hours after hatching and are then led to the nearest water by the female. Losses of young on the way to water may account for this species being scarce or lacking in areas with dense undergrowth.

Bucephala albeola / bufflehead

Photo: USFWS/Donna Dewhurst

The female tends the ducklings carefully for about a month before she departs to moult, or shed old feathers. The ducklings have to be brooded, or kept warm, frequently when small. Losses may be severe if cold, wet weather occurs when broods are less than two weeks old. Young may also be lost to pike and other predators, and on the average only about half of the young survive to fly at an age of seven to eight weeks. Meanwhile, the adult birds retreat to favoured lakes to undergo the annual moult of their flight feathers. The birds are flightless for three weeks at this time, which is usually in July for drakes and in August for females. In September, Buffleheads of all ages renew the body plumage and build up fat reserves in preparation for the fall migration.

Conservation

Many factors combine to restrict the numbers and distribution of the Bufflehead, which is one of the scarcest ducks in North America. Its use of tree holes for nest sites excludes it from both prairie and tundra habitats. The small size of its young places them at a disadvantage, compared with larger ducks, for travelling from nest to water in areas with dense ground vegetation: this probably helps to restrict the distribution to more open forests. Clearing of the parklands in the Prairie provinces has destroyed much excellent habitat. Scarcity of nest-sites, perhaps combined with predation by pike and loss of small young in poor weather, limits breeding densities over most of the range.

In excellent habitat, where other factors are not limiting, the availability of food might be expected to regulate Bufflehead numbers, but spacing of breeding pairs probably minimizes competition for food both among Buffleheads and with other ducks. There is no evidence that disease or predation—other than hunting—has ever limited numbers of these ducks.

Buffleheads are shot in most parts of North America, but they make up no more than two percent of the total Canadian duck kill. They are unwary and easy to shoot, but they provide little meat compared with most ducks, so few hunters seek them out. Typical of ducks that consume animal foods, their flesh has a rather strong taste, especially if they have been feeding on the sea. They are not an important game species, and seem unlikely to become one.

Bird watchers and aviculturists, on the other hand, prize the Bufflehead both for its striking appearance and its relative scarcity. Its activity and pattern make it one of the most easily recognized of ducks, and one of the most popular with waterfowl enthusiasts. This is a duck that is more valuable to people as an object of delight than as a hunting statistic. Long may it continue to brighten our waters.

Resources

Online resources

Audubon Field Guide, Bufflehead

Print resources

Bellrose, F.C. 1980. The ducks, geese and swans of North America. Stackpole, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Erskine, A.J. 1972. Buffleheads. Monograph Series No. 4. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1965. Handbook of waterfowl behaviour. Comstock, Ithaca, New York.

Palmer, R.S., editor. 1976. Handbook of North American Birds. Volume 2. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1974, 1985. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with corrections in 1995

Catalogue number CW69-4/40-1995E

ISBN 0-662-22941-X

Text: A.J. Erskine

Photo: Robert McCaw