Description

Measuring only 12 to 15 cm from bill-tip to tail-tip, the Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapilla is greenish-grey above with a white underside shading to light brownish buff along its flanks. Its long, dark-grey tail looks like a handle. A black cap, well drawn over sparkling eyes, covers its head from cone-like bill to nape, or back of the neck. Pure white cheek patches and a triangular black throat patch complete its most conspicuous markings. Because chickadees inhabit such a wide variety of climates and habitats, birds from different populations may vary somewhat in size and plumage.

A number of chickadee species resemble the Black-capped Chickadee. The Mountain Chickadee Poecile gambeli is distinguished from the Black-capped by a white line over the eye. In Canada, it lives only in the mountains of British Columbia and Alberta. The Mountain Chickadee is closely related to the Black-capped, and the two species hybridize, or interbreed, occasionally.

The Gray-headed Chickadee Poecile cincta is widely distributed across Asia and Europe. In North America, this brownish-grey chickadee is found in a small corner of the northwestern Yukon and eastern Alaska, where it lives in the willow and spruce woods bordering the treeline.

The Boreal Chickadee Poecile hudsonica has a seal-brown cap, greyish-brown above and dusky white or light grey below with rust-coloured sides. Its cheek patches are often dusky white and the throat patch is black. Like the Black-capped, it lives right across Canada, but resides in the belt of coniferous forest that extends to the northern treeline. Boreal and Black-capped Chickadees overlap at the edges of their breeding ranges, but do not hybridize.

The Chestnut-backed Chickadee Poecile rufescens lives in the coastal forest and southern part of British Columbia. Its brown crown and brownish-black throat match well with its chestnut back and sides.

Signs and sounds

The chickadee makes at least 15 different calls to communicate with its flockmates and offspring. The best known is the chickadee-dee-dee that gives the bird its name. Using this call both male and female chickadees challenge or scold intruders, and send information about the location of food and predators to their partners, their offspring, and members of their flock.

Male chickadees also sing a short ditty of two or three whistled notes (one higher and slightly longer, followed by one or two lower, shorter ones): feee-bee or feee-bee-bee. Males may sing at any time of the year, but do so mostly in the early part of the nesting season, peaking during territory establishment, nest-building, and egg-laying. Males sing only sporadically during the day, but serenade their females with a dawn chorus that can last from 20 minutes to an hour.

Habitat and Habits

In fall and winter, Black-capped Chickadees live in loose flocks of four to 12 birds. Each flock consists of mated pairs that bred locally the preceding summer, plus unrelated juveniles that have immigrated from surrounding populations.

From October to March, the flock flits from tree to tree over an area of 8 to 20 ha, meandering through long-established forest paths at a rate of about half a kilometre an hour. The birds keep in touch with each other by means of soft notes, sit-sit, uttered at intervals. Each flock defends its home range from other flocks using vocalizations and aggressive behaviour.

In the north, the chickadees usually roost in dense evergreen groves sheltered from the wind and snow. At roosting time, some of them disappear into any available hole where they spend the night, one bird to a hole. Others roost in the top branches of evergreens or low down in bushy young spruces. Night after night, the flock may use the same roosting place.

To keep warm the chickadee erects its soft, thick feathers to trap warm air close to its body. This serves as good insulation against the cold.

In early spring, the flock begins to break up, with paired birds spending daylight hours vigorously defending breeding territories from their former flockmates. During this period birds may still roost at night with their flock, especially during cold weather. Once breeding commences, a chickadee rarely strays from the 3 to 7 ha around its nest.

Unique characteristics

Chickadees establish a dominance hierarchy, or “pecking order,” by which each bird is known to the other according to rank. A bird’s rank is set by its degree of aggressiveness. Thus all the birds in the flock are subordinate to the most aggressive bird; and the lowest ranking is subordinate to all the others. The rest are graded in between. Typically males dominate females, and adults dominate juveniles. The higher ranking birds enjoy best access to food, the safest spots away from predators, and not only survive better but also have more offspring survive. A dominant bird will threaten, chase, and even fight the subordinate bird, which is always on the defensive and gives way to it. Dominant birds rarely need to fight subordinates once the hierarchy is established. Males and females generally pair according to rank — the dominant male pairs with the dominant female, and so on.

Range

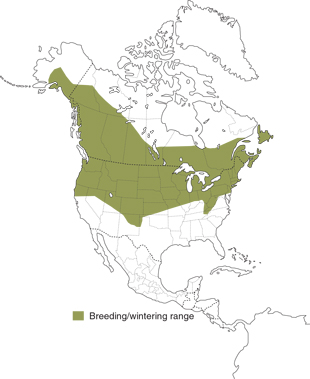

The Black-capped Chickadee is found throughout Canada, from the island of Newfoundland to British Columbia (except for the coastal islands) and extends northwards into the southern Yukon and Northwest Territories. It lives in tree-covered areas — including woodlots and orchards — where it digs its nest-holes in the soft or rotting wood of trees and finds the food it prefers.

The chickadee is ordinarily a year-round resident, but from time to time large numbers of birds move long distances, generally south in the fall, and north in the spring. These irregular movements, called “irruptions,” involve mostly young birds less than a year old. Irruptions may occur due to habitat destruction, or in years when there is a shortage of food, combined at times with an unusually successful breeding season.

Feeding

From sunrise to sunset, the chickadee spends most of its time feeding. The bird hops along a branch, clutches an upright trunk, or hangs upside down at the tip of an evergreen twig, examining every crevice and cranny for tiny hidden creatures.

The chickadee eats large quantities of insect eggs, larvae and pupae (insects in the torpid stage), weevils, lice, sawflies, and other insects, as well as spiders — about 80 to 90 percent of its diet consists of invertebrates during the breeding season, and about 50 percent during the winter. The chickadee is easily one of the most important pest exterminators of the forest or orchard.

When food is plentiful, particularly in the late summer and fall, the chickadee becomes a food hoarder. It carefully tucks a morsel away under a buckled piece of bark, or in a patch of lichens — often only to pull the morsel out again and repeat the tucking-away ceremony in another place. A chickadee may cache hundreds of food items in a single day, and can retrieve these with almost perfect accuracy 24 hours later. Some birds can remember the location of their food hoards for at least 28 days after caching. Black-capped Chickadees remember not only where they have stored different food items but also which caches they have emptied. As it gets colder, chickadees will tend to select caches with seeds that provide more energy.

Hoarding food is important to the northern birds. This habit provides a meal for whoever finds the hidden morsel, and also ensures extra supplies along customary feeding routes when food is scarce.

It is estimated that chickadees, like other small titmice, need about 10 kcal of energy per day to survive. The birds eat plenty of food which is turned into energy. During the short winter day, the rate of feeding is speeded up. Food not needed for the immediate activity of moving around and foraging is stored as fat. The fat provides energy that the chickadee needs to survive while sleeping and fasting through the long, cold night. Chickadees also drop their body temperature at night by 10 to 12°C below daytime body temperature, to conserve energy. It is easy to see how important are the foods — sunflower seeds, peanuts, and suet — offered at a feeding station in winter.

Breeding

February and March are courtship months. Calling loudly, the chickadees spend much time chasing each other. They whirl around a tree in wild pursuit, suddenly stopping as quickly as they started. The flock gradually breaks up into pairs. Each pair travels alone, the female usually in the lead. Wherever she goes, the male defends a small area around her against other chickadees.

By the end of March, the female begins looking for a nesting place. Once it is chosen, the male defends the surrounding area against intruders. This area of 3 to 7 ha forms the pair’s territory.

Together, they dig out a hole in the rotting wood of a dead stump, usually about 1 to 3 m above ground. They may also nest 9 to 12 m up in the dead parts of live trees, or in hollows abandoned by other hole-nesting birds.

Although the female looks exactly like the male, by late April she is easily recognized by her voice, which takes on a peculiarly raspy quality as she prepares to lay her eggs. The male feeds the female often, and she accepts his offerings, crouching and shivering her wings like a baby bird. This ceremony is called courtship-feeding. The female makes a soft nest bed in the nest hole, using fine fibres, plant down, and hairs, where she lays one egg a day until there are five to 10; clutches of six to eight are most usual. The eggs are white with fine dark spots.

Only the female incubates, or sits on, the eggs for 20- to 30-minute periods during the day, and for the entire night. While she is on the nest, the male feeds her, but she also leaves to look for food.

At this time, the birds are wary and secretive. Should a would-be nest robber darken her nest, the female snarls and hisses in protest. The sound is so startling that it may momentarily disconcert an attacker, making escape possible.

After 13 or 14 days, the young hatch. The female broods, or warms, the young until they are well feathered. Both parents clean the nest by carrying away the droppings, and feed the nestlings from six to 14 times an hour. A study has shown that feeding and looking after six to eight nestlings can so drain the parents’ energy reserve that there are times when they survive only with great difficulty.

After 16 or 17 days, the young are ready to leave the nest. They emerge clean and fluffy images of their parents. Like most other hole-nesting birds, they know how to fly by this time, although their ability increases with practice. For two or three weeks more, the parents continue to feed them, while they gradually learn to feed themselves.

By this time, the parents look worn out. They begin to moult, losing their feathers at a fast rate, and it is easy to tell them apart from the younger generation. The new plumage takes six to eight weeks to grow out fully. After that, young birds can only be told from the older birds by the shape and amount of white on the outer tail feathers. The family may stay together for a short time, but its members soon disperse to join the autumn flocks that tour the woods, feeding and hoarding. Young chickadees typically join flocks from one to several kilometres distant from where they were raised.

Conservation

Black-capped Chickadees are the most widespread bird species across Canada. The most recent surveys suggest that numbers are increasing: Bird Studies Canada’s 2001–2002 Christmas Bird Count documented 123 000 individuals, a 25 percent increase over the sample counts of 2000–2001. Since the Christmas Count is only a “snapshot” taken at approximately 300 locations, and since Black-capped Chickadees extend into the United States as far south as northern California across to New Jersey, it is probably safe to assume that Black-capped Chickadees number in the millions. Their success partly results from the increase in winter bird feeders, since chickadees readily adapt to these “free handouts.”

The Black-capped Chickadee’s most dangerous predators include bird-hunting hawks and the Northern Shrike. In addition, snakes, weasels, chipmunks, mice, and squirrels enter chickadee nests, or tear them open and eat the eggs or young birds. Adult females are sometimes killed on the nest by weasels.

It is worth our while to encourage and protect the hardy Black-capped Chickadee for the large part it plays in naturally controlling insects and enlivening our forests with its song and movements, even in winter.

Resources

Online resources

All About Birds, Black-capped Chickadee

Audubon Field Guide, Black-capped Chickadee

Canadian Wildlife Federation, Black-capped Chickadee

Canadian Wildlife Federation, Wild About Birds poster

Canadian Wildlife Federation, Bird Feeding handout

Print resources

Bent, A.C. 1946. Life histories of North American jays, crows, and titmice. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 191:322–393.

Christie, P. 2001. Chatting up chickadees. Seasons (Federation of Ontario Naturalists) 41:17–19

Glase, J .C. 1973. Ecology of social organization in the Black-capped Chickadee. Living Bird 12:235–267.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Lawrence, L. de K. 1968. The lovely and the wild. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York.

Lempriere, S. 1990. Flocks and fat: How Black-caps survive winter. Seasons (Federation of Ontario Naturalists) 30:44–45

Odum, E.P. 1942–43. The annual cycle of the Black-capped Chickadee. The Auk 58:314–333, 518–535; 59:499–531.

Smith, S.M. 1985. The tiniest established permanent floater crap game in the northeast. Natural History 94:42–47.

Smith, S.M. 1991. The Black-capped Chickadee. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Smith, S.M. 1993. Black-capped Chickadee. In The Birds of North America, no. 39. A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, editors. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia; The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1973, 1989, 2003. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/25-2003E

ISBN 0-662-34270-4

Text: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence

Revision: B. Desrochers, 1988; L. M. Ratcliffe, S.J. Song, S.J. Hannon, 2003

Editing: Maureen Kavanagh, 2003

Photo: Daniel Mennill