Description

The American Robin Turdus migratorius is one of the best-known birds in North America. It was given its name by the early settlers, who thought that, with its reddish breast, it resembled the English Robin. However, the American Robin is a thrush, not a robin, and except for the colour of its breast, it does not look like the small brown European bird.

The American Robin is the largest thrush in North America. The adult measures about 25 cm long and weighs about 77 g. In addition to its cinnamon-rufous to brick-red breast, the American Robin has a black head, white eye-rings, yellow bill, black and white streaked throat, and grey back. The male is generally more brightly coloured than the female.

Young birds assume a mouse-grey down shortly after hatching. This is replaced by feathers which make them resemble their parents, except for black spots on their breasts and pale streaks on their bodies. By October of their second year, they cannot be told apart from their elders.

Signs and sounds

The American Robin has a large repertoire of songs and calls. It is one of the first birds to begin singing in the morning and one of the last to be heard at night. The male is the most vocal, usually singing from high vantage points mainly in the morning and most frequently during courtship. He continues to sing until the young hatch, when he generally stops, resuming after the young fledge, or begin to fly. Perhaps the best-known song is the familiar “cheerily” carol: cheerily, cheer up, cheer up, cheerily, cheer up. The mating song is similar and is accompanied by the male displaying and lifting his tail higher than his head. The territory or whisper song, hisselly-hisselly, is soft and ventriloquistic.

In addition to their singing, robins make a variety of calls, from the well-known alarm cheep and disturbed tuktuk to a scolding chirp accompanied by tail jerking. Some birds sing in July and August, when they are moulting, or replacing their feathers, but the songs become shorter and quieter, except for a brief resurgence at the end of September. While most singing stops by the end of October, singing can be common in the winter. Calls continue throughout the year.

Habitat and Habits

The American Robin was originally a forest species, but it has adapted well to residential areas, where it feeds on lawns and nests in gardens and city parks. As trees have been planted, it has invaded the prairies, and it is often found in alpine forests and meadows above the treeline, so that there is scarcely any type of habitat, except marshes, where the American Robin will not nest. It prefers to winter in open areas, but does live in pinewoods and orange groves.

Unique characteristics

Roosting, or resting in trees, is common, especially during the non-breeding season. It seems that all American Robins gather in roosting communities in the winter, the adult males roost in the breeding season, the females after nesting is completed, and the young birds as soon as they can make the trip to the roosting area. Robin roosts can include as many as 250 000 birds, but they usually contain from 20 to 200 birds. Sometimes American Robins roost with other species, like European Starlings and Common Grackles. Roosting seems to be a way to protect against predators and to locate feeding areas, especially in winter, when the roosting groups travel about in search of food.

The American Robin has an extendible esophagus, or canal between the mouth and the stomach. This can be useful in winter, for example, when the bird may store fruits in the esophagus before it settles for the night. This probably allows the robin to survive low nighttime temperatures.

Range

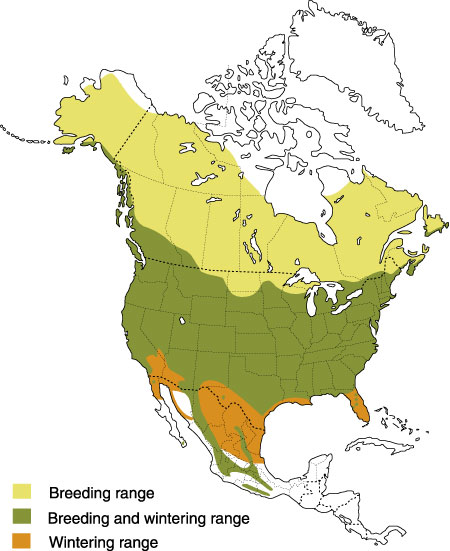

Distribution of the American Robin

The American Robin breeds north to Alaska, across Canada, and southward to the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in the United States and into southern Mexico. Northern populations migrate, spending the winter in an area that includes southwestern British Columbia and the Pacific coast of the United States, the south-central United States, the east coast of the continent as far north as the south coast of Newfoundland, and Mexico, southern Texas, and the tip of Florida in the south. In winter, robins share the edge of huge Red-winged Blackbird roosts with Common Grackles and starlings and feed with Cedar Waxwings. The southern races in the eastern United States and in Mexico do not migrate. Occasionally, when berries are abundant, a few hardy robins winter in Quebec, Ontario, and the prairies.

Migrating American Robins travel during the day. In the spring, they begin their northward movement in late February and do not arrive in any numbers in Canada until early March. The temperature rise in spring is a key factor in their migration, for the birds need thawing ground so that they can dig up earthworms. The northward migrants follow closely an average daytime temperature of 3°C. American Robins return to the same breeding area they had frequented the previous year.

In the fall, on the other hand, robins do not follow a set “route.” Instead of always returning to the same area, they seem to wander, responding to the seasonal availability of invertebrates and fruits, their main foods. They begin to migrate south in early September, but most wait until October, and large numbers pass through southern Canada in November. Birds seen in southern Canada as late as the second week of December may still be migrants. The birds usually migrate in small flocks, but may sometimes travel in groups of several hundred, frequently with Blue Jays.

Feeding

Most of us have seen American Robins on lawns, digging for and pulling up worms. However, earthworms provide only a part of the robin’s diet. Although invertebrates—such as earthworms, beetles, and caterpillars—provide about 40 percent of its diet, the robin is chiefly a fruit-eating species, with chokecherries, barberries, and rowan berries high on its list. Other favourites are sweet and sour cherries, wine grapes, and tomatoes. American Robins eat invertebrates mainly in spring and summer and fruit principally in fall and winter. Occasionally, robins eat small snakes and shrews, and they have even been known to comb the seashore at low tide for molluscs and go belly-deep in water to pick up fish fry. Although robins chiefly glean their food on the ground when hunting insects, or perch in trees while stripping fruit, they can also catch flying insects in midair. Young birds in the nest eat mostly earthworms and beetle grubs.

Breeding

American Robins begin to arrive at their breeding grounds in southern areas of Canada in early March and continue to arrive at northern breeding areas until as late as mid-May. Flocks of up to a dozen males arrive first as the snow recedes; females sometimes arrive the same day but are usually a week, or even more, behind their mates. Robins generally remain together for the breeding season, but often mate with other individuals the following year. Most breeding adults return to the same general area each year, but young birds usually nest elsewhere.

Courtship is hard to define in the robin and usually takes place on the ground. Numerous fights occur during this period. Courtship includes courtship feeding, where the male feeds the female; ceremonial gaping, where the males and females approach each other and touch widely opened bills; and singing.

The male may visit the area where the nest will be located before the nest is built, and he may bring nesting material to his mate, but the female chooses the nest site and builds the nest. Although robins prefer to nest about 3 m above ground in spruce and maple trees, they readily adapt to a wide range of vegetation and built structures. They will even nest on the ground. Robins also reuse nests from the previous year, either their own or those of other species such as the Eastern Phoebe, the Catbird, the Common Grackle, and the Baltimore Oriole. Sometimes they build a new nest on top of an old one, which may have yet another nest under it, and lay the eggs in the new nest at the top.

The female makes the cup-shaped nest of mud mixed with grasses or small twigs and frequently with string, scraps of cloth, and small bits of paper. She works mud into place with her feet and bill, moulds it with her body, and lines the nest with fine grass. She takes from two to six days to build the nest, making an average of 180 trips a day, with mud or grass, during the peak building period. If the weather is bad, she may delay occupying the nest for as many as 20 days.

In southern Canada, the first clutch, or set of eggs, is laid in late April or early May. This is commonly followed by a second clutch and, at times, when conditions are favourable, a third. Nests may still contain eggs in early August. A clutch of three or four eggs is common.

The eggs are the familiar robin’s-egg blue, though white ones, rarely brown spotted, do occur. The female generally begins incubating, or warming, the eggs after the last egg is laid, and she continues incubating for an average of 12 days. She usually sits on the eggs for 40-minute periods, then stands on the rim of the nest, turns the eggs, and flies off for a break. The male frequently stands guard when he is not in the feeding area and may occasionally sit on the eggs.

The nestling period lasts from 13 to 16 days. The next clutch is usually started about 40 days after the first egg of the year, but females often start the second nest, including laying the eggs, before the first group of young is independent. Sometimes the overlap is extensive, with the second clutch begun before the first nestlings are out of the nest. When this happens, the male cares for the first nestlings.

The young weigh about 5.5 g when they hatch. Fed by both parents, they each receive an average of 35 to 40 meals a day. The parents keep the nests clean by carrying away or eating the chicks’ fecal sacs.

When they are about 13 days old, the young leave the nest, travelling up to 45 m on the first day. They may remain in the parents’ territory for three weeks and may be fed by the male while his mate is on the next clutch. The young become independent of the parents at four weeks.

Conservation

Young American Robins do not have a strong chance of survival. It has been estimated that only 25 percent live until the beginning of November of their first year. Most birds live about two years, so that within six years, there is an almost complete turnover in population.

Robins have many predators. The chief one in residential areas is the domestic cat. In winter roosting areas, bobcats and Great Horned and Barred Owls take a toll. Other predators include raccoons, grey and red squirrels, chipmunks, hawks (especially the Sharp-shinned), crows, jays, grackles, and snakes, which prey on the eggs and young. External parasites include lice, flies, ticks, and mites.

Robins do considerable damage to cherry and grape crops, and to olive orchards and tomato fields while on their wintering grounds. At one time, people shot robins in the fall for the pot. Farmers still scare and shoot robins in orchards or in tomato or blueberry fields to prevent damage to the crops, but they must obtain a Permit Respecting Birds Causing Damage to do so, as these birds are protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act.

A Canadian Wildlife Service biologist who studied methods of scaring birds away from dropped fruit found no effective and economical method. Acoustic bird-scaring devices and netting of grape vines are effective, but these cost far more than the damaged crops.

Photo: Leslie McKim, Cornell

While they cause some crop damage, robins may also play a part in controlling insects, such as alfalfa weevils, which they eat in large quantities.

Unlike many species, the American Robin has adapted quite well to habitat disturbance. The loss of forests, the growth of urban areas, and the increase in the size of farms have created, rather than degraded, breeding habitat for this bird.

The American Robin continues to be well-loved, and the harbinger of spring to most communities in Canada.

Resources

Online resources

The University of Maine – American Robin Fact Sheet

Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology – American Robin

Journey North – American Robin

United States Geological Survey – American Robin

Print resources

Eiserer, L. 1976. The American Robin, a backyard institution. Nelson-Hall Inc., Chicago.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Livingston, J.A., and J.F. Lansdowne. 1970. Birds of the eastern forest. McClelland and Stewart, Toronto.

McRae, S.B., P.J. Weatherhead, and R. Montgomerie. 1993. American Robin nestlings compete by jockeying for position. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33:101–106.

Montgomerie, R., and P.J. Weatherhead. How robins find worms. 1997. Animal Behaviour 54:143–151.

Pettingill, O.S., Jr. 1963. All-day observations at a robin’s nest. In The living bird. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

Sallabanks, R., and F.C. James. 1999. American Robin (Turdus migratorius). In The Birds of North America, no. 462. A. Poole and F. Gill, editors. The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1973, 1989, 2003, 2005. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/35-2003E-IN

ISBN 0-662-34261-5

Text: R. Charles Long

Revision: Barb Desrochers, 1988; Patrick Weatherhead, 2003

Editing: Maureen Kavanagh, 2003, 2005

Photos: Robert McCaw; Leslie McKim, Cornell Lab of Ornithology