Canada’s Peatlands

Mer Bleue bog, Ontario

- Peatlands are wetlands where dead Sphagnum moss – as well as other mosses, sedges and woody plants forming peat – accumulates over time.

- More than third of the world’s peatlands are in Canada, and they cover about 14 per cent of Canada’s territory.

- There are three types of peatlands: bogs (a Gaelic word meaning “soft ground”), fens (an Icelandic word for “quagmire”) and some swamps.

- Many plants and animals have special adaptations to cope with the very wet conditions found in peatlands.

- Peatlands are home to a relatively small number of species specialized for these unique habitats, some commonly found at more northern latitudes.

- Peatlands play an important role in the biosphere, acting as carbon stores, which help regulate climate.

- Peatlands are archives and can reveal a great deal about a region’s natural and cultural history.

Description

Fen peatland

In the past, peatlands were considered soggy, barren wastelands. But to those who learn more about them, they become unusual, fascinating and complex ecosystems. Peatlands are wetlands that are different from marshes, shallow open-water wetlands and most swamps because of the buildup of layers of peat. This peat creates the unique conditions found in these wetlands.

The first 30 to 50 centimetres of the surface of a peatland is mostly formed by living mosses and plants. Peat is found under this living layer. Peat is made up of the dead and decomposing Sphagnum mosses and the many other wetland plants that were once living at the surface, over which new, living plants have grown. This peat is typically several metres deep; it can even exceed 10 metres in some locations! Since peat is very absorbent, it acts like a compact sponge saturated with water, which makes it difficult for water to circulate through. This keeps water levels in peatlands high, just below or at the surface. A peatland’s high water table is important in maintaining wet conditions that favour other wetland plants, as well as providing water storage that may reduce downstream flooding or be slowly released in times of drought. As with certain other wetlands, a peatland’s plant tissue can absorb heavy metals and other contaminants, nutrients and sediments, and so it can clean up contaminated water.

Conditions in peatlands are unique. Decaying peat produces humic acid, making peatland water acidic (its pH is low), nearly as much as vinegar. Also, the water in the peat is anoxic (with low oxygen content) and has low levels of nutrients, such as nitrogen. These conditions, added to the low soil temperatures of northern latitudes, make decomposition a very slow and difficult process below the surface. Many decomposing microorganisms lack much of what they need to survive in the peat layers, so instead of quickly decomposing when it dies, the moss accumulates as new moss grows at the top. Some peatlands in temperate, boreal, subarctic and arctic climates have been forming for more than 10,000 years, or since the end of the last ice age. It takes about 10 years for one centimetre of peat to form, but in areas with high rainfall, moss growth is more rapid, and peat accumulates faster. This accumulation, instead of decomposition, leaves large amounts of dead plants remains as peat, which is made of 40 per cent carbon. So instead of being released in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2 is one of the products of decomposition and a greenhouse gas), carbon is stored in the peatland. This is why the world’s peatlands are the most important terrestrial carbon stores; they contain about 30 per cent of the global soil carbon and are important regulators of climate change.

Because decomposition rates are very low in peat, peatlands can become an archive of an area’s natural and cultural history. Pollen, leaves, animals and human artifacts from the peatland itself and its surroundings can get caught in the moss and become preserved because of the special conditions in the peat. Many thousands of years afterwards, scientists can find remains of the species that lived close by and reconstruct what type of environment was there in the past.

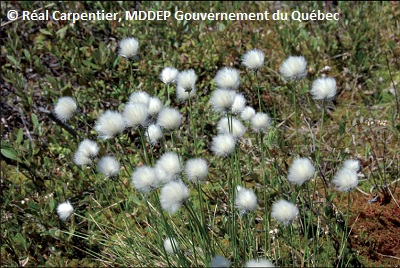

Cottongrass

In Canada, most peatlands are bogs or fens. They differ in how water enters the ecosystem, making them very distinct from one another. The source of water affects the water chemistry, and this can strongly affect the type of vegetation communities, including the Sphagnum moss species, that are found in the ecosystem.

Bogs, or ombotrophic peatlands, get their water exclusively from precipitation, including rain, fog and snowmelt (ombotrophic, means “derived from rain”). This precipitation water contains little or no dissolved minerals and nutrients, so the acids that are produced by decomposing vegetation cannot be neutralized. This is why the water in bogs is acidic and has low nutrient content. Oxygen levels are also very low below the bogs’ surfaces. These conditions, and the fact that a bog’s wildlife can be unprotected from the wind and sun, make their biodiversity fairly low. Some bogs form as moss grows over a small isolated lake or pond and slowly fills it, but most were created by moss growing on moist landscapes, with the peat eventually preventing water from leaving the surface. Depending on what type of vegetation grows on top of the bog, they are sometimes referred to as open (very little standing woody vegetation), shrubby (with low shrubs) or treed (with some small trees).

Fens are minerotrophic peatlands, which get water not only from precipitation but also from groundwater or sometimes streams. Because of their varied water sources, fens tend to be richer in dissolved minerals and nutrients, and they are typically not acidic, having a more neutral or alkaline pH (pure water has a neutral pH). These conditions can make decomposition more rapid than in bogs, so peat accumulation can be slower and is often not as thick as in bogs. As fen conditions are not as harsh, their biodiversity is generally higher than what is found in bogs. They can occur at the edge of lakes and rivers, and, like bogs, can also be open, shrubby or treed. Strips of fens sometimes border larger open water areas in bogs.

Some shallow, well-decomposed peat may accumulate in some areas of swamps, making these swamps peatlands as well.

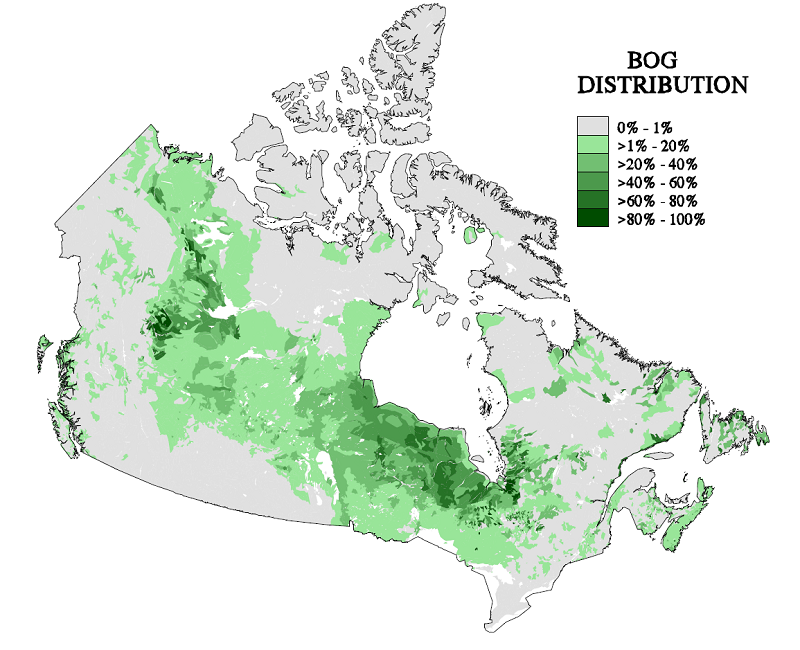

Bog distribution in Canada © Department of Natural Resources Canada. All rights reserved.

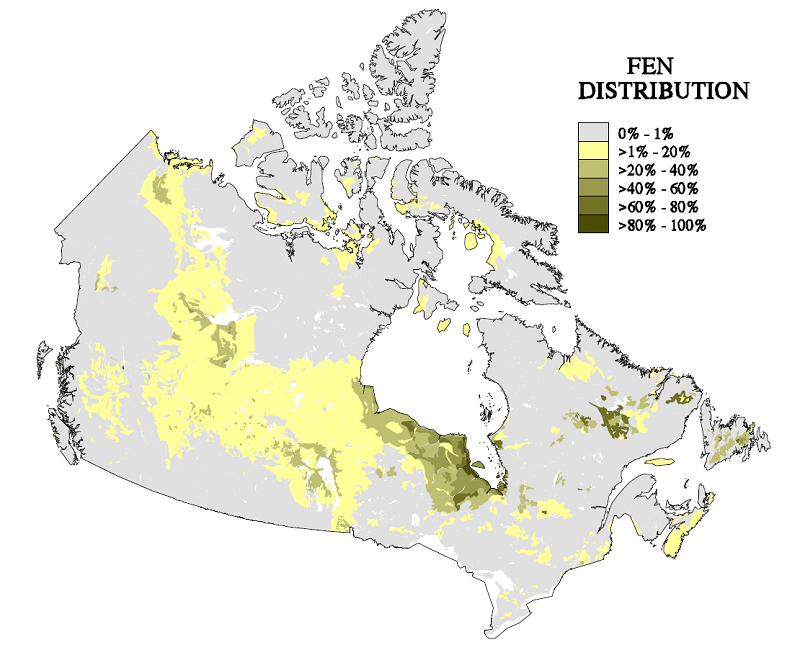

Fen distribution in Canada © Department of Natural Resources Canada. All rights reserved.

For a more complete picture about the distribution of peatlands in Canada, have a look at this PDF from the Department of Natural Resources Canada.

Globally, peatlands occupy 3 to 4 per cent of the land surface, approximately 4 million square kilometres. Peatlands occur worldwide. Some tropical peatlands exist under the shadow of forests in Asia, Central and South America and Africa. In Canada, they occur throughout the country, but are more common in boreal, subarctic and arctic areas. They cover about 170 million hectares of our country, about 14 per cent of the total surface of Canada. Also called “muskegs” (an aboriginal term for “soggy ground”), fens and bogs are the most extensive wetlands in our boreal forest.

Plants and Fungi

Pitcher plant flower

The most dominant and widespread peat-forming species in peatland ecosystems are Sphagnum mosses. They are keystone species, meaning that they modify their environment to create many peatland ecosystems. There are roughly 120 species of Sphagnum mosses worldwide. Like most mosses, or Bryophyta, Sphagnum mosses are soft, small plants with short leaves. Mosses typically grow in humid environments. Since they do not have roots to gain water with, they absorb their water through their leaves, which are only a single cell thick. They also lack seeds and rely on wind to spread their spores around in order to reproduce. They can hold a lot of water in their tissues, like a sponge, which helps them survive in drier periods. Sphagnum mosses grow in mats, submerged or floating over water, which can often withstand the weight of a large moose!

The layers of peat and live mosses form a substrate in which other plants may grow. Because of the low levels of nutrients and oxygen, especially in bogs, plant diversity is often restricted to specialized species. Plants that grow in peatlands must adapt in order to thrive in their unusual conditions – for example nodules with bacteria in their roots to help gather and keep nutrient reserves. In fens, where plant diversity is higher than in bogs, herbs, ferns, grasses and sedges grow. Some of these plants can also grow in bogs, like cotton grass, but low-lying shrubs, like cranberry, bog laurel, leatherleaf, blueberry and Labrador tea, are more common. Other plants found in peatlands include rhododendrons and orchids, which use a symbiosis, or association, with fungi in their roots, called mycorrhizae, to get extra nutrients. In the open-water areas of peatlands, lily pads and a few other water plants can grow. Peatlands tend to be very colourful ecosystems from spring to fall, as plants “flower” at different times over the spring and summer seasons rather than compete against each other for pollinators. And in the fall, after the first frost, some shrubs’ leaves turn the bog or fen orange and red!

Mushroom in Sphagnum moss

Most peatlands contain carnivorous plants. These plants, like sundews, bladderworts and pitcher plants, can compensate for the lack of nutrients in the soil by capturing small

insects and spiders. Prey are attracted by the sweet sticky liquid on (in the case of sundews) or contained by (in the case of pitcher plants) their leaves, and get stuck when they touch it. When it has captured a prey, the plant produces digestive liquids and absorbs the dissolved insect remains through its leaves, thereby getting its nutrients.

Trees can grow in peatlands, but only where their roots can stay out of the water long enough for them to survive. The most common trees include bog willow, black spruce, tamarack and grey and white birch. While some may reach normal sizes, many stay small because of the low amount of available nutrients and oxygen, high water levels and wind exposure.

More than 600 species of fungi have been inventoried in bogs and fens in the Northern Hemisphere. This includes those that form symbioses with plants or algae, like mycorrhizae and lichens. Most are microfungi, or very small fungi, but some species can be seen at the surface as mushrooms. Some researchers think that these fungi, more so than bacteria, may be responsible for most of the decomposition that happens in peatlands.

Wildlife

Fish

Small fish, like minnows, have been observed in open-water areas of peatlands, but unlike other wetlands, fish diversity is not large because of the acidity, low oxygen and low nutrient levels in the water. In shallow ponds, fish may not survive the winter because of low oxygen and ice cover, but some find their way back to peatlands the following summer.

Birds

Lincoln’s Sparrow

Peatlands provide habitat to millions of songbirds, raptors and waterfowl, mostly migrators mating or visiting them in the summer. A few species, like the Palm Warbler and the Lincoln’s Sparrow, heavily rely on peatlands, having adapted perfectly to these unique ecosystems. Peatlands are great habitat for Tree Swallows, which can feast on the great quantities of flying insects. Northern Harriers nest in the tall grasses. Forest-living Spruce Grouse may prefer these open habitats sheltered from most predators during the summer months. Shorebirds, geese and ducks, including the Black Duck and the Solitary Sandpiper, can be seen near or on open-water areas of peatlands.

If a peatland offers a variety of different habitats, for example, different types of vegetation covers and the presence of open water, bird diversity is higher than in more uniform peatlands. Also, larger peatlands are important to some birds like the Savannah Sparrow, the Palm Warbler and the rare Upland Sandpiper.

Mammals

Southern Bog Lemming

Some large mammals can be found in peatlands. Moose, white-tailed deer, wood bison and caribou pass through areas where moss mats are thick and strong enough to withstand their weight and where they can walk without their long legs being hindered. Some herds of woodland caribou choose peatlands specifically as their winter habitat, since they forage on the many species of lichens found there. These ecosystems are important for the species’ conservation. Black bears, wolves and bobcats can also be observed visiting peatlands in search of food.

Smaller mammals are more common and diverse than larger ones. Lemmings, voles, mice, snowshoe hares, minks, shrews, muskrats and red squirrels find food and shelter in peatlands. Not many small mammals are peatland specialists (those that live mostly in peatlands throughout their lives), but the northern bog lemming, southern bog lemming and Arctic shrew prefer peatlands to other habitats. Beavers are also common in peatlands, and they have been known to alter them and flood them by damming the surface water seepage.

Reptiles and Amphibians

Smooth Greensnake

Because of peatlands’ unusual conditions, they are home to fewer amphibians than other types of wetlands. Given the high water acidity, few species breed successfully in bog water, with the exception of green frogs and wood frogs. However, other amphibian species still occur in bogs of eastern Canada, namely, the leopard frog, the mink frog, the American toad, the spring peeper, the spotted salamander and the blue-spotted salamander.

Because many peatlands are in colder areas, reptile diversity is very low. Still, spotted turtles and eastern garter snakes are often found there. Also, the eastern Massasauga rattlesnake is an inhabitant of Southern Ontario fens, as is the smooth greensnake in Eastern Quebec.

Butterfly on a Flowering Leatherleaf

Invertebrates

Within the layers of peat, microfauna adapted to low oxygen levels – bacteria, protists, etc. – work at decomposing the dead Sphagnum moss. But because of the unusual water conditions, especially in bogs, peatlands have much less diversity of invertebrates other wetlands do.

Insects are often the first group of wildlife one will come across when someone is visiting a peatland. An estimated 6,000 species of aquatic and terrestrial arthropods – spiders, insects and other invertebrates with an outer skeleton – may be found in peatlands, with a higher diversity in fens. Experts think that about 1 per cent of these species live only in peatlands, especially in bogs, and are bog specialists. But in both fens and bogs, many species of terrestrial arthropods – including flies, mosquitoes, dragonflies, damselflies, wasps, beetles and spiders – thrive.

Disturbances and Threats

Thread-leaved Sundew

Since Canada is so large, and much of it is inaccessible, precise statistics on peatland destruction and disturbance are difficult to obtain. But we do know that in the north of our country, where very few people live, many areas, amounting to about 90 per cent of Canada’s peatlands, have been more or less left untouched. Still, some have been flooded because of hydroelectricity developments or damaged by clear-cutting from the forestry and mining industries. In the more heavily populated south, peatlands were, and sometimes still are, seen as wastelands. In some areas, peatlands have been almost completely drained and destroyed to make way for farms, and some are still under threat of urban development. Several peatlands are currently being threatened by cranberry farming, which involves flooding or draining, and by peat mining. Peat has long been used around the world as fuel for heating homes. Nowadays, it is used by gardeners as a growing medium.

Disturbing peatlands releases their carbon stores into the air and stops the area from retaining new carbon until restoration work is done. It may also have an effect on local water quality, as some peatlands prevent heavy metals from flowing out of the wetland. Fragmentation, or the division of a peatland by a road or by partial draining, also disturbs the water dynamics in the peatland.

Because of these threats, some species inhabiting Canada’s peatlands are now at risk. These species include the thread-leaved sundew (a carnivorous plant living in Nova Scotia bogs), the eastern ribbon snake, the spotted turtle, the Massassauga and many others. The woodland caribou, which spends its winters in peatlands, is also at risk.

Peatlands take thousands of years to form. When they are damaged, it can take years for Sphagnum and other plants to recover and regrow and for peat layers to reform. Also, peatlands are often already isolated from one another, making it even more difficult for peatland specialist species to move to or pollinate other areas when their habitat is disturbed.

Actions

Moose

As peatlands have now been recognized as valuable ecosystems, many areas have been protected in Canada. Some peatlands are protected in national parks, for example Wapusk National Park, which contains the most extensive area of polygonal peat plateau bog in Canada, or the deep coastal peat bogs of Kouchibouguac of New Brunswick. Other peatlands are protected at the provincial level. Manitoba, for example, has protected as much as 25 per cent of its peatlands! Under the International Convention on Wetlands (also known as the Ramsar Convention), some internationally important peatlands (including the Mer Bleue Bog in Ottawa) are now protected.

As for the peatlands’ wildlife, several species in Canada are protected. The Migratory Birds Act prohibits the deposition of harmful substances in areas frequented by migratory birds, including peatlands, and the Species at Risk Act prohibits damage or destruction of the habitat of an Endangered or Threatened species. These measures help conserve the peatlands these species inhabit.

Getting to know peatlands better is also helping in their conservation, and after being poorly understood for hundreds of years, peatlands are now unlocking their secrets! Their hydrology, geochemistry, microbiology, ecology, biodiversity and conservation are being studied by researchers, and ways to help restore them are being developed. Peatland restoration efforts aim to allow the ecosystem to start accumulating carbon again, to regulate water flow and to support a variety of habitats and species. Scientists are also trying to find a way to cultivate Sphagnum moss so that it may not be mined in natural ecosystems in the future.

What You Can Do

Eastern Prairie Fringed-orchid

A great first step in helping peatlands is to get to know them and to talk about them. Learn about the peatlands that are close to where you live and, if possible, visit them to have a look at these amazing ecosystems. If you do visit a peatland, stay on boardwalks or other structures, as in some areas moss mats might not be thick enough to carry your weight and you might sink. Even if you are confident about the moss’s thickness, do not trample the peatland’s vegetation, as Sphagnum moss does not easily recover from damage.

You can also help by finding alternatives to peat products used for gardening. Compost can replace peat while using up some of your household’s garbage! Also, you can aerate your soil after adding compost, or choose native plants that grow in the soil in your area.

Scientific Reviewers

Grande Plée Bleue, Québec

Dr. André Desrochers, Centre d’étude de la forêt, Université Laval

André-Philippe Drapeau Picard, Université Laval and Peatland Ecology Research Group

Dr. Peter Lafleur, Trent University

Dr. Marc J. Mazerolle, Centre d’étude de la forêt, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue

Dr. Jonathan Price, University of Waterloo

Dr. Line Rochefort, Université Laval and Peatland Ecology Research Group

Dr. Maria Strack, University of Calgary

Dr. Barry G. Warner, University of Waterloo

Spruce Bog in Algonquin Park, Ontario

Resources

Grass Pink Orchid

Why Wetlands?

https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/why-are-wetlands-important

Peatland Ecology Research Group

http://www.gret-perg.ulaval.ca/tourbieres-gret.html?&L=1%2520%2F

The Mer Bleue Bog

http://www.ncc-ccn.gc.ca/places-to-visit/greenbelt/mer-bleue

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands

https://www.ramsar.org/search?search_api_views_fulltext=Wetlands

Peatland Fires and Carbon Emissions

http://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/pages/381?lang=en_CA

What is a Wetland?

https://www.ducks.ca/our-work/wetlands/

The Wetland Network

http://www.wetlandnetwork.ca/index.php

Peatlands

http://www.wetlands.org/?TabId=2737

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2013. All rights reserved.

Text: Annie Langlois