Description

The North American elk, or wapiti, is the largest form of the red deer species Cervus elaphus. In general appearance elk are obviously kin to the well-known white-tailed deer. However, elk are much larger. Among Canadian deer, they are second in size only to the moose. An adult bull elk stands about 150 cm tall at the shoulder and weighs about 300 to 350 kg, although some large bulls approach 500 kg in late summer before the rut, or breeding season. Cows are substantially smaller but still have a shoulder height of 135 cm and an adult weight of around 250 kg.

The colour of the elk’s coat ranges from reddish brown in summer to dark brown in winter. Although it looks white from a distance, on closer inspection the rump colour is ivory to orange. In contrast to the rump, the head and neck are dark. Elk have long, blackish hair on the neck that is referred to as a mane.

Male elk are notable for their impressively large antlers. It is amazing that these large structures are grown new each year by the animals in a period of a few months in spring and summer. Antlers look particularly large in summer when they are encased in velvet—a covering that protects them during growth. In later summer, the velvet is rubbed from the fully grown antlers, revealing the bony structure. Newly cleaned antlers are light grey in colour but become stained by rubbing and thrashing through vegetation during the rutting season.

“Elk” is the name by which most Canadians know this majestic deer. “Wapiti,” meaning “white rump,” is the Shawnee Indian name and the common name preferred by scientists, because the animal known as an “elk” in Europe is not a red deer at all but a close relative of the North American moose. Other red deer, smaller and belonging to several subspecies, are found throughout the northern hemisphere: in Scotland and continental Europe, in North Africa, and in Asia.

Signs and sounds

Elk Tracks

The elk is highly vocal for an ungulate, or hoofed animal. A person close to a group of elk can hear frequent grunts and squeals as they keep in touch with each other. When alarmed the cows give sharp barks to warn the rest of the group. The whistling roar of rutting bulls is a spine-tingling sound on a frosty autumn morning.

Elk hooves are rounded and their tracks may be confused with those of yearling cattle in range country.

Elk scat, or droppings, like those of other deer, are in the form of pellets in winter, but in summer, when the animals are on new green forage, resemble those of cattle. Closer inspection, however, reveals traces of a pellet structure.

Droppings

Habitat and Habits

Elk are sociable animals. They are seldom found without other elk nearby. The herd lifestyle is characteristic of animals that live in open country. However, elk populations today occupy forest or parkland regions, where small groups averaging six or seven animals are common.

Elk are long-lived animals: males survive to an average of 14 years, whereas females live as long as 24 years. Although they may travel widely, each elk is strongly attached to certain localities within its home range. Some in fact have home ranges of only a few square kilometres. Others have home ranges of several hundred square kilometres, of which they use different parts during different seasons. In the mountains such individuals often summer in the high country and winter in the valleys. However, elk are versatile animals and some may reverse this pattern or make visits back to their summer range during winter, snow conditions permitting, and down to their winter range during summer. Others may even switch between staying in a small area one year and using a large area the next.

Bulls may occupy a “rutting range” that is separate from localities where they are found during the rest of the year. Whatever their seasonal pattern, most elk use the same ranges year after year.

Unique characteristics

Unlike other deer, elk have upper canine, or “eye,” teeth. These teeth are a hangover from earlier evolutionary stages and now serve no apparent purpose. Their smooth rounded surface has made them attractive as jewellery. In the 1800s many elk were killed just to obtain the canine teeth.

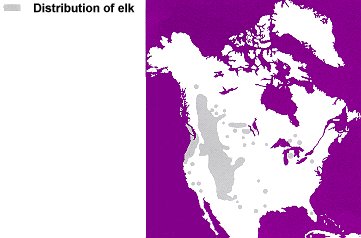

Range

When Europeans arrived in Canada, elk were widely distributed. Their range extended across southern Quebec, along the upper St. Lawrence (where they were probably one of the species recorded but ambiguously described by Jacques Cartier), and into southern Ontario. Their range continued around the northern margins of lakes Huron and Superior and along the present American border from the Lakehead to the prairies of Manitoba, but in these areas their populations were sparse. Farther west, on the prairies of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, and north into the southern fringes of the boreal forest—the northernmost forest of the Northern Hemisphere—elk were numerous. In British Columbia, elk were found throughout the central and southern parts of the province east of the Coast Range, in the Lower Mainland around the mouth of the Fraser River and on Vancouver Island.

When Europeans arrived in Canada, elk were widely distributed. Their range extended across southern Quebec, along the upper St. Lawrence (where they were probably one of the species recorded but ambiguously described by Jacques Cartier), and into southern Ontario. Their range continued around the northern margins of lakes Huron and Superior and along the present American border from the Lakehead to the prairies of Manitoba, but in these areas their populations were sparse. Farther west, on the prairies of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, and north into the southern fringes of the boreal forest—the northernmost forest of the Northern Hemisphere—elk were numerous. In British Columbia, elk were found throughout the central and southern parts of the province east of the Coast Range, in the Lower Mainland around the mouth of the Fraser River and on Vancouver Island.

Relative to western populations, numbers of elk must have been low in eastern North America, except in regions like western Kentucky, where the forests were interrupted by extensive grasslands. In any case, hunting extirpated elk from the east, including southern Ontario and Quebec, by the mid-1800s. Some elk may have survived in Ontario north of Lake Huron.

Relative to western populations, numbers of elk must have been low in eastern North America, except in regions like western Kentucky, where the forests were interrupted by extensive grasslands. In any case, hunting extirpated elk from the east, including southern Ontario and Quebec, by the mid-1800s. Some elk may have survived in Ontario north of Lake Huron.

Settlement of the Canadian prairies deprived the elk herds of their habitat as it did the bison. However, scattered populations continued to exist throughout the forest regions skirting the prairies and in the mountains of the west.

Elk numbers were at their lowest around 1900 in North America. Thereafter the pace of settlement in marginal areas slowed, market hunting was greatly reduced, the number of people living subsistence lifestyles declined, predators were reduced, and elk received increasing legal protection. Also, large forest fires caused by settlers converted substantial areas from forest to grass, shrubs, and saplings, providing abundant forage for the remaining elk.

Elk were also reintroduced to areas of former range. In Canada’s Rocky Mountains the small remaining elk population in Banff and Jasper national parks was dramatically increased by several hundred animals brought from Yellowstone National Park in the United States between 1917 and 1920. Elk were also transplanted to northern Ontario in the 1930s. In British Columbia elk were introduced to the Queen Charlotte Islands and, in Yukon, elk were introduced northwest of Whitehorse in the early 1950s. The Yukon herd has maintained its numbers but has not grown.

The present population of elk in Canada is about 72 000. Over half of the animals (40 000) are in British Columbia, mostly in the Kootenays and in the Peace-Omineca Region, but with a small population on Vancouver Island. Alberta’s 20 000 elk roam mainly in the Rocky Mountain foothills and the mountain national parks of Banff, Jasper, and Waterton. A scattered population exists in the parkland across central Alberta, where the boreal, or northernmost, forest meets the grassland and the creation of Elk National Park has made a notable contribution to the survival of elk in Canada. The park grew from a reserve established in 1906 to protect a small band of remaining elk. The elk thrived, and currently the fenced park of less than 200 km2 supports over 1 000 elk as well as moose, bison, and white-tailed deer. Elk Island has provided many elk for reintroductions and has also served as a research area for study of the species.

Manitoba currently has a herd of around 7 000 animals, whose distribution centres on Riding Mountain National Park. The 15 000 elk in Saskatchewan are mostly in the southern fringe of the boreal forest north of Prince Albert and in the Moose Mountain, Cypress Hills, and Duck Mountain areas in the south of the province.

Feeding

Elk are plant eaters. There are few plants that occur on their range that they do not eat in certain areas under certain conditions. In winter they eat grasses when they can obtain them. However, when the snow becomes deep, they readily eat twigs of woody species, even the conifers like Douglas fir. In spring, grasses and sedges are favourite foods. As the new growth of broad-leaved herbaceous plants spring up in early summer, elk include a high proportion of them in their diet. They also consume shrub and tree twigs and leaves. A wide variety of nutritious foods become available for elk early in summer. This is also the time when cow elk are providing milk for their newborn calves.

As summer passes, the herbaceous plants dry out and elk turn again to dry grasses and browse, or twigs and shoots. When the frosty nights of autumn arrive, leaves begin to fall in trembling aspen forests on the western ranges of the elk. Elk include dry leaves in their diet until these are buried by snow. When winter comes, elk diets are controlled largely by snow. Elk dig craters in loose snow to expose dry grass and leaves, but when the snow becomes too deep or too hard they must shift their feeding largely to woody twigs. In the mountains of Alberta and British Columbia elk must leave areas of deep snow cover and seek locations such as valley bottoms where snow cover is shallow or absent. In areas where deep snow seldom occurs, they may frequent high- or low-elevation ranges at any time of the year.

Breeding

The annual cycle of the elk begins in spring with release from the snows and food shortage of winter. This is when calves are born, increasing the herd size. Calving usually occurs in areas with which the cow is very familiar. Some cows may seek the same area to calve in year after year. Others give birth to their calves wherever in their home range they happen to be when the time comes. The cows split off from other elk and seek seclusion and cover a few days before giving birth.

Elk hide their calves for 10 days or more after they are born. The calves are genetically programmed to remain quiet and concealed as a defense against predators. Later, mother and offspring join others in cow/calf bands on the summer range. Beginning in August, the quiet summer life of the elk comes to an end with the start of the rut, or breeding season.

The bulls, which have passed a lazy summer in small groups while their antlers grew large and heavy, now move into the cow/calf group and establish harems, or groups of cows they plan to mate with. In the process there is considerable fighting among the bulls. Large bulls eventually get control of as many as 20 or 30 cows and drive other males to the fringes of the herds. This does not mean, however, that the young males are totally left out of the breeding. While the large harem masters are running off intruders or rounding up straying females on one side of their group, a young bull may sneak in and mate with a female on the other side.

Following the turmoil of the rut, the bull elk leave the females and move to good foraging areas to recoup their losses in weight and condition before winter. Some go back up the mountains to spend a few more weeks on the nutritious pastures of the alpine zone before snow forces them down. Elk usually, but not always, wait for coming of snow to move down to the valleys. There is considerable overlap between the winter ranges of bulls and cows. As bulls are larger and more powerful they can travel and dig through deep snow more readily than the cows, and by doing so they are able to have foraging areas to themselves.

Conservation

The principal limiting factor on the number of elk in Canada has been loss of habitat to agriculture. Fortunately, extensive areas do remain to the elk. Hunting serves to keep elk numbers within the carrying capacity of the ranges. In parks, capture and transplant of surplus animals sometimes reduces elk numbers.

Aside from humankind, the most important predator of elk is the wolf. In spite of their size and power, elk are readily killed by wolves. The distribution of elk in Canada overlaps with wolf distribution, so most elk herds are culled to some extent by wolves. Black bears also kill considerable numbers of elk. Recent studies have demonstrated that in some areas black bears may kill as many as 50 percent of the elk calves. This predation occurs during the first two or three weeks of the calf’s life. Once calves become strong enough to keep up with their mothers, and mother and calf rejoin the rest of the herd, most bear predation ceases. However, grizzly bears may kill an occasional adult elk. Coyotes take some calves, and cougars, which share the elk’s range from the Rocky Mountains west, take elk of all ages.

Where predation and hunting do not keep them low, elk numbers usually increase until they are limited by lack of food. At high population levels, elk can have a significant impact on their range and on their food plants by grazing, browsing, and trampling on vegetation. During severe winters or droughts, significant numbers of elk may starve or become predisposed to disease. The managers of many of the Canadian elk populations that are not in parks aim to keep numbers well below the maximum dictated by food resources so that elk will be less likely to experience die-offs.

Elk are highly esteemed by hunters and are one of North America’s major big game species. In Canada licensed hunters take approximately 4 000 elk each year. The hunt generates local economic activity estimated at about $14 million per year. In addition, aboriginal hunters take an unknown number. In parks where elk are not hunted, they gradually become habituated to the presence of humans. They may eventually become so tame that they go about their business undisturbed even when people approach closely. Large numbers of habituated elk may be seen in Banff and Jasper national parks in and around the townsites, especially in early spring. Habituated elk are important attractions in those parks and are an asset of substantial aesthetic and commercial value. It must always be kept in mind that animals habituated to humans may be dangerous if approached too closely. Bulls, especially, should be given a wide berth during the early autumn rutting season.

In mountain areas during winter, elk share valley bottoms with major transportation corridors. This leads to many elk-vehicle collisions, with disastrous results to the elk and to humans and their automobiles. This costly hazard has been controlled in Banff National Park by construction of a system of fences, cattleguard gates, and underpasses along the Trans-Canada Highway.

The readiness with which elk can be habituated to people and the value of products derived from them have recently aroused considerable interest in domestication and ranching of the animals. One of the most valuable elk products is their antlers. Since ancient times, Oriental people have believed that medicinal preparations from elk antlers that have been removed while still in velvet are a general tonic and possibly an aphrodisiac, or means of enhancing sexual desire. Thus Oriental medicine consumes large quantities of elk antler at a high price. Antlers are surgically removed when they have reached maximum size but before they harden; then they are dried, sorted by grade, and shipped to Asian markets.

In many areas elk and domestic cattle share the same ranges. Because both eat the same foods and the presence of cattle brings human activity, there is some conflict between the two species. In mountain areas where elk concentrate in valleys that are also important winter range for cattle there is competition for scarce forage and disturbance of elk at a time when they are under stress due to severe weather. Such situations call for close cooperation between ranchers and wildlife managers to keep problems under control.

The future welfare of elk in general depends on cooperation between wildlife authorities and all land managers, including forest industries, oil and mining companies, park managers, and Indian bands, as well as ranchers.

In spite of these ongoing conflicts, Canadian elk populations are stable and healthy. It might be possible to reintroduce the animals to areas they formerly occupied, but, given the competing demands for land by ranchers and others, and the space needed by the wild predators of the elk, which are vital to a healthy ecosystem, the current elk population is probably large enough. With adequate attention to its management this splendid wild species will remain a permanent asset to Canada.

Resources

Print resources

Murie, O.J. 1951. The elk of North America. Stackpole Company. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Boyce, M.S., and L.D. Hayden-Wing, eds. 1979. North American elk: ecology, behaviour and management. University of Wyoming, Laramie.

Thomas, J.W., and D.E. Toweill, editors. 1982. Elk of North America. Wildlife Management Institute and United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and Stackpole Company, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1990. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/89E

ISBN 0-660-13639-2

Text: E.S. Telfer

Photo: Robert McCaw