Species at Risk in Canada

- Since the arrival of the first European settlers, more than 30 wildlife species have become extinct in Canada.

- At present, over 500 plant and animal species are considered at risk in Canada.

- Everywhere in Canada, people are engaged in recovery activities that benefit more than 200 species.

- All Canadians can take simple actions every day to help species at risk.

Soapweed is a plant at risk in Alberta.

Is the status of species at risk in Canada serious

Since the arrival of the first European settlers 500 years ago in what would later become Canada, at least 13 of our plant and animal species have disappeared entirely from the Earth and at least 20 others are no longer found in Canada. At present, according to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), which is responsible for assessing the status of wildlife species believed to be at risk, over 500 species are at risk in Canada. However, many other living organisms, including several invertebrates (animals without backbones, like worms or insects) and marine fish, have not yet been assessed. Consequently, the number of species at risk in Canada will continue to grow over the years as the committee focuses on these species.

The pink milkwort is at risk because its natural habitat is being lost to agricultrual use and urban development.

The pink milkwort is at risk because its natural habitat is being lost to agricultrual use and urban development.

Why at risk?

Why do species become at risk in Canada?

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Canadian beaver was endangered because of the popularity of the hats that used to be made with their fur. Fortunately, men’s fashions changed before every beaver was exterminated. In the 1930s, governments prohibited beaver trapping and reintroduced the animal in places where it had been eliminated by trappers. Beaver populations were able to recover without difficulty because their habitat was still intact.

Today, Canada’s wild plants and animals face new threats, notably the destruction of their habitat and contamination of their environment. More insidious than hunting and trapping, these threats are also much more difficult to counter. Certain types of habitat are disappearing at a tremendous rate in almost all parts of Canada. Wetlands are being filled in, forests fragmented, and grasslands ploughed and fenced.

As is the case in many wealthy countries, the modern lifestyle of Canadians depends to a great extent on chemical products used in industry, around the house, and in agriculture. Unfortunately, these products pose a serious risk to the health of wildlife species.

Acid precipitation is another threat. The acidity produced by some pollutants can kill numerous aquatic organisms, damage soils, and have adverse effects on forests.

Ever since it first became apparent that the Earth’s temperature was gradually rising, more and more scientists have come to fear that climate change will affect certain species. In Canada’s North, climatic changes are modifying ice conditions, threatening the long-term survival of several species, including the polar bear.

“Invasive” species are another serious problem for wildlife species that occur naturally in Canada (known as indigenous or native wildlife species). Most invasive species come from foreign countries and have been introduced into Canada through human activity. These so-called exotic species are able to invade the territories of native wildlife species and replace them.

The status of the anatum subspecies of the Peregrine Falcon has improved everywhere in Canada.

The status of the anatum subspecies of the Peregrine Falcon has improved everywhere in Canada.

Identifying species at risk

How do we know that a species is at risk?

In Canada, a species is considered at risk when it may disappear entirely from Canada or the Earth if nothing is done to improve its status. COSEWIC is the organization that assesses the status of species believed to be at risk. Established in 1977, this committee is composed of members representing federal, provincial, and territorial agencies responsible for managing wildlife, experts from the scientific community, and specialists in community and Aboriginal traditional knowledge. COSEWIC members assess reports dealing with the status of wildlife species that are believed to be at risk. They then assign these species to one of the following five categories:

Extinct — A wildlife species that no longer exists.

Extirpated — A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

Endangered — A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

Threatened — A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

Special concern — A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

Under the Species at Risk Act (SARA), the Government of Canada takes the designations made by this committee of experts into consideration when establishing the List of Wildlife Species at Risk.

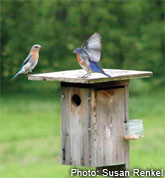

The Eastern Bluebird has recovered because of the installation of many nesting boxes.

The Eastern Bluebird has recovered because of the installation of many nesting boxes.

Recovery efforts

Why is it so important to preserve wildlife species?

When living organisms are unable to adapt to changes in their natural environment, they die. Others, better adapted, take over. The extinction of species is a biological reality that has existed since life first appeared on Earth. If extinction is the outcome of a natural process, why should we be concerned about the disappearance of wildlife species today? The extinction of species nowadays is a concern not because it occurs, but because it is happening more and more quickly.

The decline of populations and the disappearance of wildlife species modify ecosystems considerably, both in Canada and elsewhere in the world. Plants, animals, and micro-organisms all play essential roles in the natural processes that keep the Earth’s atmosphere, climate, landscape, and water in balance.

An ecosystem is a natural community—like a forest, a grassland, or a marsh—in which all the species depend on one another and their environment. When one component of the environment is modified, the entire balance of this community is threatened.

Green plants are the foundation. By taking carbon from the air and energy from the sun, they make their own food and produce the oxygen we breathe. They also serve as food for plant-eating animals that, in turn, support predators. Finally, decomposers, like fungi and bacteria, recycle the nutrients and energy contained in plant debris and dead animals so that the nutrients and energy can be reused by other living organisms.

In the short term, there are also practical reasons, just as urgent, for conserving wildlife species:

- Wild animal and plant species are an important source of basic ingredients for traditional remedies and pharmaceutical formulations. Many plants have healing properties.

- The gene pool of wildlife species (the entire set of genes that determines the characteristics, like resistance to disease or to parasites, of a given species) continues to provide basic materials that can be used to improve livestock and food crops.

- A good number of Canadians, notably Aboriginal people, count on wildlife species for food, clothing, and shelter, and also as a source of spiritual inspiration.

- Others depend on the income they earn from activities like hunting, fishing, trapping, logging, and bird-watching that are closely tied to wild animals and plants.

How do we help species at risk?

In Canada, we help species at risk in various ways: there are provincial and federal laws to protect them; scientists, Aboriginal peoples, private landowners, and industries implement recovery strategies; communities help with stewardship and conservation efforts; and many Canadians get involved by taking part in a number of these endeavours.

Stewardship is the management of spaces and species to ensure that they will be preserved for future generations of Canadians. It encompasses all kinds of habitat restoration and conservation initiatives.

The effects of urbanization are harmful to the Maritime ringlet, a species at risk.

The effects of urbanization are harmful to the Maritime ringlet, a species at risk.

What legislation deals with species at risk?

Canada was one of the first industrialized nations to sign the Convention on Biological Diversity at the Earth Summit, held in Brazil in 1992. In doing so, Canada confirmed its commitment to conserve biodiversity and species at risk. Biodiversity, or biological diversity, refers to the great variety of living organisms present on the Earth.

In 1996, the Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act (WAPPRIITA) came into force. This act protects Canadian and foreign species from illegal trade activity. It also helps protect Canada’s ecosystems by prohibiting the introduction of certain invasive species.

In 2002, the Canadian government passed the Species at Risk Act (SARA). It protects species at risk and the natural habitats essential to their survival. It also requires federal organizations to draw up recovery strategies for listed species within tight timelines.

In addition, six provinces—Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba—have specific laws to protect species at risk. Several provinces have amended existing wildlife laws to deal explicitly with species at risk, while other provinces and territories are working on developing legislation.

What measures are being taken to help species recover?

Throughout Canada, recovery strategies for threatened, endangered or extirpated species are prepared and implemented under the supervision of a team of specialists. The efforts of everyone who wants to help—governments, wildlife management councils, Aboriginal peoples, non-governmental organizations, businesses, and individuals—are thus effectively coordinated.

Every year, over 250 organizations (governments, municipalities, Aboriginal peoples, industries, and environmental organizations) invest approximately $40 million in recovery strategies for over 200 species at risk. More than a quarter of this amount comes directly from three programs that provide financial support: the Habitat Stewardship Program for Species at Risk, the Endangered Species Recovery Fund, and the Interdepartmental Recovery Fund.

Some good news

Over the years, the status of certain species has improved. The anatum subspecies of the Peregrine Falcon, which was designated “endangered” by COSEWIC in 1978, was moved in 1999 into the “threatened” category, a lower risk category. This bird of prey had been declining as a result of the use of pesticides such as DDT, which is now banned in Canada. More than 1 550 Peregrine Falcons were raised in captivity and released into the wild in order to support recovery of the species.

The American White Pelican, which was designated “threatened” by COSEWIC in 1978, was re-assessed and determined not to be at risk in 1987. This species has established many nesting colonies. The Trumpeter Swan, whose status was “special concern” in 1978, now has a population of more than 20 000 birds and is growing in number. It is no longer considered at risk. The Eastern Bluebird is another species that recovered completely, thanks to the many people who put up nesting boxes.

Encouraging examples of recovery activities

The white-top aster, a species at risk.

White-top aster

The white-top aster is a plant with tiny white daisy-like flowers. It is one of the numerous rare species found in Garry oak ecosystems. These ecosystems are a combination of woodland, wildflower meadows, grassland with scattered trees, and rocky clearings; they hold many species found nowhere else in Canada. More than 20 of these plant species are considered to be at risk by COSEWIC. The only Garry oak ecosystems in Canada are all located in areas with mild climates in southwestern British Columbia.

Over the course of the last 150 years, most natural environments in southwestern British Columbia have been converted to agricultural land, cities, and suburban areas. Today, local communities and the Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team, as well as provincial and federal governments, are working together to protect the last remaining tracts of these unique ecosystems. Stewardship agreements have been signed with private landowners who wish to restore or protect the habitats on their properties.

Invasive alien species, like Scotch broom and English ivy, are another serious threat to the last Garry oak ecosystems.

The white-top aster is protected in an ecological reserve and in several parks, where efforts are being made to control a number of invasive species. The plant has disappeared from most sites outside these protected areas.

Massasauga

The massasauga, a species at risk.

The massasauga used to be called the eastern massasauga rattlesnake. When it shakes its tail, small bony plates at the end of its tail knock against each other and make a clicking sound. The massasauga is a venomous snake: it uses its venom to kill its prey and to defend itself. It rarely bites humans, unless provoked, and with basic medical care, there are almost never any long-term effects. In Canada, the massasauga is found only in Ontario.

For a long time, people have deliberately killed snakes, including massasaugas. The public awareness campaign organized by the massasauga recovery team encourages people to treat this venomous snake with a healthy mix of fascination and prudent respect. Among other things, a number of Ontario residents are now helping the province’s only species of rattlesnake to recover; they report their sightings to the Natural Heritage Information Centre, protect or restore natural habitats on their properties, and post “snake crossing” signs at strategic places where large numbers of snakes have been killed by road traffic.

The North Atlantic right whale, a species at risk.

The North Atlantic right whale, a species at risk.

North Atlantic right whale

The North Atlantic right whale is one of the most endangered large marine mammals. Although the population has grown somewhat since laws protecting it from hunting were adopted in the 1930s, it is nevertheless still at risk today. In 2004, the entire population of the species numbered about 300 individuals.

The North Atlantic right whale is a migratory species. Because it spends a great deal of time at the ocean’s surface and migrates along the coast where maritime traffic is heavy, the greatest threats to it are collisions with ships and becoming entangled in fishing gear.

Since 2000, efforts have been under way to help the North Atlantic right whale recover, with representatives from the Canadian government and non-governmental organizations, scientists, and those involved in fisheries, shipping, and marine mammal observation all working together. In response to recommendations made by this team, a certain number of projects have come into being, notably the Eubalaena Award. Launched by the Canadian Whale Institute in 2001, this competition encourages people to propose modifications to fishing gear that would reduce the potentially fatal injuries whales suffer when they become entangled in fishing gear.

In 2003, the International Maritime Organization agreed to change shipping lanes in the Bay of Fundy to keep ships away from North Atlantic right whale habitat.

How to help

Young people are restoring the habitat of the Piping Plover, a bird at risk.

Young people are restoring the habitat of the Piping Plover, a bird at risk.

What can the public do to help species at risk?

By adopting legislation, creating parks and reserves, and setting up teams of experts to help species at risk, governments help to maintain biodiversity. But each and every one of us also has a role to play. Individual Canadians can do much to protect species at risk and habitats threatened with destruction.

- Families can avoid using cleaning products and pesticides that are toxic.

- Gardeners can avoid planting invasive alien species.

- Communities, private landowners, and industries can preserve natural habitats that shelter wild plants and animals.

- Hikers can refrain from leaving their garbage behind and avoid disturbing wildlife species.

- Farmers and loggers can try to reduce their use of pesticides, keep run-off and erosion to a minimum, and protect landscapes that are suitable for wildlife species.

- Motorists can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which are responsible for climate change, by using public transit, car-pooling, walking or cycling, or teleworking.

Above all, Canadians need to make sure economic development supports the long-term survival of wildlife species. The extinction of too great a number of species can upset the ecological balance, and our own species—like so many others—may ultimately be threatened. Healthy natural ecosystems, rich in wild plants and animals, help to ensure the health and economic prosperity of present and future generations.

Resources

Online resources

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Species at Risk

Habitat Stewardship Program for Species at Risk

Environment Canada, Species at Risk

Species at Risk Act Public Registry

Print resources

Beacham, W., F.V. Castronova, and S. Sessine (editors). 2001. Beacham’s guide to the endangered species of North America. 6 vols. Gale Group, Detroit.

Bergman, C. 2003. Wild echoes: encounters with the most endangered animals in North America. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois.

Canadian Forestry Association. 2004. Canada’s forests: a fine balance. Volume 5: Species at risk CFA Teaching Kit Series. Canadian Forestry Association, Pembroke, Ontario.

Donald, R.L. 2001. Endangered animals. A true book. Children’s Press, New York.

Ellis, R. 2004. No turning back: the life and death of animal species. Harper Collins, New York.

Fandel, J. 2003. Endangered plants. Endangered plants and animals of North America. Lake Street Publishers, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Fandel, J. 2003. Endangered trees and shrubs. Endangered plants and animals of North America. Lake Street Publishers, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Mackay, R. 2002. The Penguin atlas of endangered species: a worldwide guide to plants and animals. Penguin Group, New York.

RENEW. 2005. Saving the wild: an opportunity to participate in species recovery in Canada. Ottawa.

Wilcove, D.S. 1999. The condor’s shadow: the loss and recovery of wildlife in America. W.H. Freeman and Co., New York.

To learn more about species at risk in Canada, call 1-800-OCANADA.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment, 2007. All rights reserved.

Text: Johanne Champagne, 2005

Revisions: Hélène Gaulin, Environment Canada, 2007