Description

|

| Sea Otter |

The Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris) is the smallest marine mammal in North America – males measure 1.2 metres in length and weigh an average of 45 kilograms (females are a bit smaller). At the same time, the Sea Otter is the largest member of its family, the mustelids, which includes River Otters, weasels, badgers, wolverines and martens. It’s also the only member of its family that doesn’t need land at all; it’s completely adapted to life in the water. It may come to land to flee from predators if needed, but the rest of its time is spent in the ocean.

The Sea Otter’s fur is one of the thickest in the animal kingdom, with 150,000 or more hairs per square centimetre. It varies in colour from rust to black. Unlike seals and sea lions, the Sea Otter has little body fat to help it survive in the cold ocean water. Instead, it has both guard hairs and a warm undercoat that trap bubbles of air to help insulate it. The otter is often seen at the surface grooming; in fact, it is pushing air to the roots of its fur.

The front limbs of the Sea Otter help it grab food, while its hind limbs are paddle-shaped to propel it in the water. It steers using its thick tail, and is capable of speeds of more than five kilometres per hour.

Signs and sounds

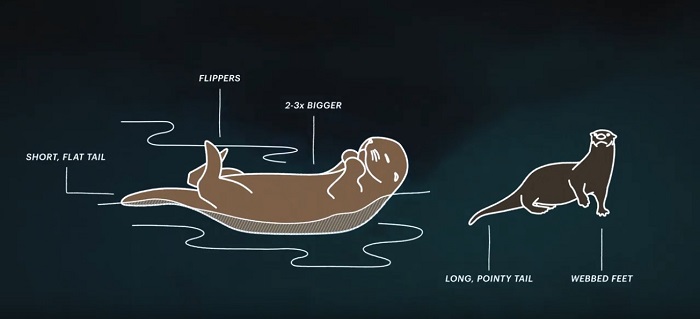

Sea Otters, which are only found in the ocean, are often mistaken with River Otters, which can be found in both fresh and saltwater. River Otters have longer, thinner tails and webbed hind feet. And they are about half the size of Sea Otters. While River Otters need land to give birth to its three or four pups, Sea Otters give birth to their one pup out at sea.

|

| River Otter |

|

| Differences between Sea and River Otters |

The Sea Otter’s main predators include Killer Whales and sea lions, but large birds of prey can grab the pups from the surface of the water.

Habitat and Habits

|

| Sea Otter at the surface of a kelp forest |

The Sea Otter lives in areas where it can dive for food in the Pacific Ocean, most often within one to two kilometres from shore where the water is no more than 40 metres deep. Shallow rocky reefs and kelp forests are ideal for prey abundance, but also for resting (or rafting) in their calmer waters. In calm weather, otters tend to be active in exposed areas, but they will head for bays and inlets during storms, especially in the winter.

Sea Otters are found in a wide range of water temperatures, but they are restricted by the Arctic sea ice in the north. They are not migratory.

|

| Kelp forest |

Range

|

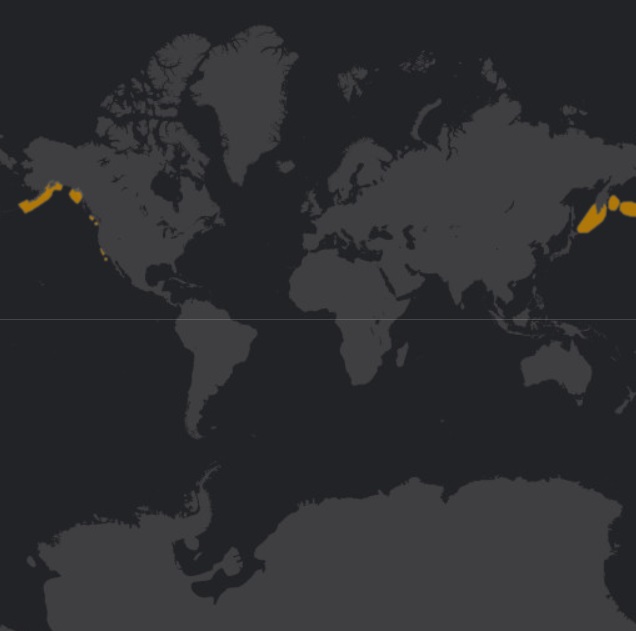

| Distribution of the Sea Otter |

Sea Otters can be observed in the North Pacific. Historically, they ranged from northern Japan to central Baja California, Mexico, but their range is not as extensive now.

There are three recognized subspecies of Sea Otter: Enhydra lutris kenyoni, Enhydra lutris nereis and Enhydra lutris lutris. Enhydra lutris kenyoni is the one found on the coast of British Columbia.

Based on habitat requirements of the otter, much of the British Columbia coast was probably occupied by sea otters historically. Today, the Sea Otter occupies only 25-33 per cent of its historic distribution in Canada.

Feeding

|

| Sea Otter eating an urchin |

The Sea Otter gets its food by diving. It can’t go very deep since it dives for less than five minutes. Because it lives in cold water without much of a fat reserve, it needs to eat a lot – about 20 per cent of its body weight each day.

When diving, the otter finds food with the help of its sensitive whiskers and nimble front paws. It goes to the bottom of the water column, sometimes turning rocks, to find invertebrates like clams, mussels, chitons, snails, prawns, crabs, abalone, sea urchins, squid and sea stars. Sometimes, it will catch fish as well.

A well-known image is that of an otter floating on its back, cracking its prey by hitting it in the stomach with a rock. This makes the Sea Otter one of the few animals that uses a tool. The otter even keeps its favourite rock in a pouch of skin under its front legs, using it wherever it goes.

|

| Sea Otter with an urchin |

Breeding

|

| Sea Otter raft |

Male and female otters don’t tend to live together. They form different groups, or rafts, which float together by holding hands. At any given point during the year, a male will visit a raft composed of females. It forms bonds with many mature females at the same time (called polygyny), mating with each one. But the female otter doesn’t start its pregnancy just yet. Instead, through a process called delayed implantation, conception takes place within four to 12 months, followed by four months of actual pregnancy. The female gives birth, most often in the spring, to one or very occasionally two pups every year or two. A pup, which weighs from 1.4 to 2.3 kilograms, stays with its mother for six to eight months after it is weaned. A mother keeps its pup very close, often on her stomach, and secures it to kelp when diving for food.

|

| Sea Otter with pup |

Females live 15 to 20 years in the wild, while males live only 10 to 15 years.

Conservation

|

| Sea Otter |

Sea Otters were of some importance to West Coast Indigenous Peoples – they are depicted in their art and featured in their stories. Otters were hunted by Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years prior to European contact, but with colonization in 1741 and the growth of the fur trade, populations dramatically declined. In the early 1900s, the species was considered extirpated, meaning that none remained in Canada. In 1911, Sea Otters became protected, but it took until 1969 to 1972 for the species to be reintroduced. At that time, 89 otters were released in British Columbia, but only about 28 survived.

Now, the population has grown to just less than 3,500 individuals, but since this number is still low, the Sea Otter is a Species at Risk in Canada. After being originally designated Threatened by the Species at Risk Act, it became a species of Special Concern in 2009 since the population was recovering. Sea Otters are vulnerable to oil spills, disturbance by human activities, entanglement in fishing gear and collisions with vessels.

Scientists consider the Sea Otter to be a keystone species – one that modifies and creates its habitat. When it was gone from Canadian waters, kelp forests declined because urchins and other animals that eat seaweed weren’t controlled by the otter preying on them. With the return of the otter, kelp forests are in much better shape. This is important because healthy kelp forests provide habitat to fish and reduce coastal erosion by slowing water currents.

So the Sea Otter is not just an adorable creature, but an important one too!

What we can do

Si vous voyez une loutre de mer, signalez-le ici : http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/mammals-mammiferes/seaotter-loutremer/index-fra.html

Resources

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/seaOtter-loutredemer-fra.html

https://faune-especes.canada.ca/registre-especes-peril/species/speciesDetails_f.cfm?sid=149

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/mammals-mammiferes/seaotter-loutremer/index-fra.html

Écrit par: Annie Langlois