Description

The porcupine Erethizon dorsatum is one of Canada’s best-known mammals, both in life and in legend. Its fame stems from its coat of quills, which keeps most enemies at a respectful distance.

When sitting hunched high up in a tree, a porcupine could be mistaken for the nest of a squirrel or a crow, but close to the ground it is easily recognized. It has a short, blunt-nosed face with small eyes. The ears are small and round, almost concealed by the hair, which also covers the spines. The shoulders are humped, making the back look arched. The short legs are bowed, and the animal stands bear-like with its entire foot planted firmly on the ground. The claws are long and curved. On the hind feet the first digit is replaced by a broad movable pad that allows the animal to grasp branches more firmly when climbing. The muscular tail is thick, short, and rounded at the tip.

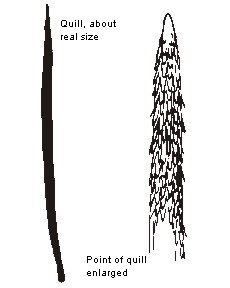

The porcupine’s coat consists of a soft, brown, woolly undercoat and coarse, long guard hairs. At the base, each guard hair is brown, becoming darker near the tip, which may be white in eastern populations and yellow in the western ones. The guard hairs conceal the quills until the porcupine is aroused. The quills are longest on the back and tail and when raised push the guard hairs forward, forming a crest. On the face the quills are about 1.2 cm long; on the back they may be up to 12.5 cm in length. There are no quills on the muzzle, legs, or underparts of the body.

Each quill is hollow and embedded in the skin, where it is attached to a small muscle that pulls it upright in the fur when the animal bristles with alarm. About 0.6 cm from the tip, the quill tapers to a fine point closely covered by several dozen small black barbs. These barbs feel only slightly rough to the touch, but when they are moist—as when embedded in flesh—they swell, working the quill farther in. The quills have black tips and yellow or white shafts.

Each quill is hollow and embedded in the skin, where it is attached to a small muscle that pulls it upright in the fur when the animal bristles with alarm. About 0.6 cm from the tip, the quill tapers to a fine point closely covered by several dozen small black barbs. These barbs feel only slightly rough to the touch, but when they are moist—as when embedded in flesh—they swell, working the quill farther in. The quills have black tips and yellow or white shafts.

It has been estimated that the porcupine has over 30 000 quills, so it is not incapacitated by a single encounter with an enemy, when several hundred quills may be dislodged. As the quills are lost they are replaced by new ones, which are white and sharp and which remain firmly anchored in the skin until they are fully grown.

The porcupine is Canada’s second largest rodent, next to the beaver. Adult males reach an average weight of 5.5 kg after six years; the females reach 4.5 kg. The total length averages 68 to 100 cm, and the height at the shoulders is about 30 cm.

Signs and sounds

When in a den or up a tree, a porcupine is not always easy to see, but noisy chewing, cut twigs, and missing patches of bark may advertise its presence. Around feeding trees and especially outside the winter dens, scats, or droppings, are often visible. In the winter, these are rough and irregular in shape; in summer they tend to be rounded and soft turning from greenish brown to dark brown as they age.

In winter, the tracks can be recognized by the firm print of the whole sole placed heavily on the ground, the long claw marks, and, sometimes, marks where the tail has dragged. If the snow is soft and deep, the porcupine trail becomes more of a trough through the snow.

In fall, and to a lesser extent at other times of the year, porcupines may be called by a low puppylike whine repeated up and down the scale.

During confrontations, a porcupine will chatter its teeth. Otherwise porcupines are mainly uncommunicative animals. The female may nose her young with subdued grunts and whines. Only in the mating season do porcupines become noisy, creating a variety of moans, screams, grunts, and barks.

Habitat and Habits

Although the species of porcupine found in North America always lives among trees, it does not always live in mature forests and may be found in alder thickets along rivers and in dwarfed pine scrub along ridge crests. It is most common where there are rocky ledges and rock piles suitable for dens and stands of aspen, hemlock, and other trees.

Being shortsighted and slow moving, the porcupine is not too difficult to approach once found.

The defensive behaviour of the porcupine is well known though sometimes misinterpreted. If on the ground when danger threatens, the porcupine will make for the nearest shelter, under a rock or log or up a tree, even forsaking its slow walk for a clumsy gallop. If thwarted in such a retreat, it will hump its back, tucking its unprotected head between its shoulders. With all the quills erected, the porcupine will pivot on its front feet and keep its back to the enemy. As it stomps its back feet, it also lashes its tail threateningly. The momentum of the tail may detach loose quills, which fly through the air, giving the impression that they were thrown.

When caught in a trap, a porcupine may, in its struggles, embed its own quills in itself. It removes these quills—or foreign quills from another porcupine—with considerable dexterity using teeth and front paws.

A treed porcupine will survey danger with an air of unconcern, but should the enemy start to climb the tree, the porcupine will back down flicking and lashing its tail.

For much of the year the porcupine enjoys no social life and leads a solitary existence. Porcupines group together for winter denning or food rather than social reasons. Several porcupines may gather around a favoured food, and up to a hundred have been found in large rock piles in winter. At these times they are usually tolerant and ignore each other totally, although there may be some teeth chattering over food. Young porcupines are often playful and shadowbox using their tails. Sometimes even the normally rather sedate adults are known to play.

During winter the porcupine does not hibernate. However, it does not usually move far and feeds within 100 m of its den. During snow or rain it will remain in the den or, if outside feeding, will sit hunched in a tree, even during subzero weather, until the rain or snow stops. When the weather is dry in winter it will feed at any time of the day or night, but during the rest of the year it is nocturnal despite the weather. In summer the porcupine ranges farther from the den, often searching for food up to 1.5 km away. As well as these daily movements within the home range, there may be seasonal movements between winter denning areas and the summer feeding areas. In mountainous country, the porcupines will often descend during the winter along well-defined routes marked by debarked trees. In the spring, they return up the mountainside to summer feeding areas.

Unique characteristics

Aboriginal people dye porcupine quills and use them in decorative work. Before the Aboriginal people moved to reservations they ate a lot of porcupine meat, especially in winter, and later they hunted the porcupine’s worst enemy, the fisher, for its fur.

Range

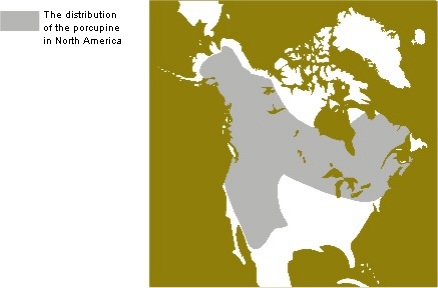

The porcupine occurs in North America in a wide range of vegetation types from semi-desert to tundra. Porcupines also occur in Africa and Asia, but Old World porcupines do not belong to the same family as New World porcupines.

Feeding

The porcupine feeds largely on the inner bark of trees in winter, but it will also feed on a variety of other plants. During winter, although the needles and bark of most trees are acceptable, there are clear favorites: yellow pine in the west, white pine in the Great Lakes area, and hemlock in the northeast states. When the sap rises in spring, the bark of maples is favoured along with the catkins and leaves of alder, poplar, and willow. As more plants come into leaf, the porcupine will eat the leaves of herbs and shrubs, such as currant, rose, thorn apple, violets, dandelion, clover, and grasses. Particularly sought after are the succulent leaves of water lily and arrowhead, for which the porcupine will wade out into streams and even swim, its air-filled quills helping it to keep afloat. In the fall, it will eat beechmasts, or beech tree nuts, and acorns and is not averse to raiding cornfields and orchards.

One of the porcupine’s best-known and least-liked eating habits is that of chewing wood and leather in and about camps. It gnaws both salty and non-salty objects, which indicates the habit may stem not only from a craving for salt, but also from a need to hone the continuously growing teeth. When human-made objects are not available, the porcupine will chew bones and cast-off antlers.

The porcupine is a slow and deliberate feeder, relying on its nose rather than its eyes to guide its selection of plants. This has sometimes led people to believe that porcupines are stupid. However, porcupines are said to have good memories and to be intelligent animals that are capable of learning quickly.

Breeding

Porcupines first breed when they are one or two years old. In the southern part of their range they mate in September, but in the more northerly latitudes, in late October to November. The male will follow the female during this period and serenade her with grunts and humming. The female is in heat, or sexually receptive, for only eight to 12 hours and frequently initiates courtship. When she is ready to mate, she indulges in a kind of dance with the chosen male, where they both rise on their hind feet to embrace, all the while whining and grunting. Sometimes they place their paws on each other’s shoulders and rub their noses together; then they may cuff each other affectionately on the head and finally push one another to the ground. Mating used to be the subject of considerable speculation and ingenious theories, but the explanation is simple. The female flattens her quills and twists her tail out of the male’s way so he can mount in the normal fashion. Mating finishes abruptly and either one of the partners then climbs a tree and screams at the other if further approaches are made.

The gestation, or pregnancy, is about 30 weeks; birth occurs sometime between March and May depending how far north the porcupine is located. The female makes almost no preparations for the birth and does not seek out a nesting den or bed. The solitary baby (twins are almost unknown) may be born in a rock pile, under a log stump, or under a brush pile.

The baby porcupine is well developed at birth: its eyes are open, and the blunt incisor teeth and molars are already exposed. About 30 cm long, it weighs approximately 0.4 kg and is covered in dense black hair. The sharp barbless quills are soft and concealed in the hair. Within hours of birth the quills harden and can be erected. After a couple of days, the baby porcupine can climb, although it tends to spend more time on the ground. After a week or so, the female leaves the baby for longer and longer periods while she feeds on the emerging green plants. Weaning, or making the transition from mother’s milk to other food, takes seven to 10 days, although in captivity it may take longer. By the fall, most young porcupines live apart from their mothers.

Conservation

Being slow moving, the porcupine is a frequent victim in forest fires and on roadways. Injuries from climbing are not uncommon, and diseases, especially rabbit fever, take their toll. External parasites, such as ticks and lice, and internal parasites, round worms, tape worms, and thread worms, are plentiful, although they apparently have no ill effects on the porcupine.

Porcupine quills have been found embedded in several predators, including the coyote, cougar, bobcat, red fox, lynx, bear, wolf, fisher, and Great Horned Owl. Some more experienced predators learn to avoid the quills and kill the porcupine by biting its head or by flipping the porcupine onto its back to expose the unprotected belly. The fisher is the best-known porcupine hunter. It was successfully introduced into some areas of New England to reduce porcupine populations.

European colonists caused a decrease in the fishers, by trapping them and deforesting the southern part of their range. The consequent increase in the number of porcupines coupled with the fact that porcupines damage and even kill some trees led to their being branded as pests. However, a study in a red spruce area in Maine, with 20 to 28 porcupines per 2.5 km2, showed the loss of trees was only 0.5 percent. They are also considered to be pests because of their habit of gnawing buildings around camps. In areas where porcupines are a problem, they are shot, trapped, or poisoned using salt baits. However, not all that the porcupine eats is upsetting to humans. For example, mistletoe, a parasite on trees, is a favoured food. Also the porcupine’s habits of thinning out dense stands of saplings and of killing weed trees are considered to be good forestry practices.

Resources

Print resources

Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. The National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Curtis, J.D. 1944. Appraisal of porcupine damage. Journal of Wildlife Management 8(1):88–91.

Lawrence, R.D. 1970. Wildlife in Canada. Revised edition. Nelson, Don Mills, Ontario.

Roze, U. 1989. The North American porcupine. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Seton, E.T. 1929. Lives of game animals. Volume 4. Garden City, New York.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2001. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/60-2001E

ISBN 0-662-29725-3

Text: Anne Gunn

Revision: C.G. Van Zyll de Jong, 1993

Photo: Parks Canada/B. Morin/06.60.10.01(01)