Description

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

For a variety of reasons, including its rarity, scientists know very little about this rather large animal. For example, there is little data on the longevity of Right Whales, but photo identification on living whales and the analysis of ear bones and eyes on dead individuals can be used to estimate age. It is believed that they live at least 70 years, maybe even over 100 years, since closely related species can live as long.

Unique characteristics

The Right Whale has a bit of an unusual name. It is thought to have been named by whalers as the “right” whale to hunt due to its convenient tendencies to swim close to shore and float when dead. Its name in French is more straightforward; baleine noire, the black whale.

Signs and sounds

Given the fact that it has no distinguishable pattern on its tail, like the Humpback Whale does, and very little elsewhere on their bodies, researchers identify individual Right Whales with the help of their pale callosities. The callosities’ patterns are unique to each individual.

Given the fact that it has no distinguishable pattern on its tail, like the Humpback Whale does, and very little elsewhere on their bodies, researchers identify individual Right Whales with the help of their pale callosities. The callosities’ patterns are unique to each individual.

While whale watching, the Right Whale can be identified by a few signs:

– Its lack of dorsal fin

– In its feeding zones, it can form large frolicking groups at the surface, called social active groups (SAGs)

– Its blow, or spout, which is distinctively V-shaped when seen along the length of the body, and which can reach seven m in height

Habitat and Habits

Although the North Atlantic Right Whale is exclusively aquatic, it does need to breathe oxygen from the air like all other mammals. Between trips to the surface for a gulp of air, its dives last between six and eight minutes, but a Right Whale can dive for up to 60 minutes. It tends to remain in the upper 100 m to 150 m of water below the surface, since its prey is mostly found there, but can dive as deep as 200 m. Whales achieve this by slowing their heart rate, focusing their blood circulation in areas of the body where oxygen is most needed, and having specialized blood and muscles able to store more oxygen and to use it more efficiently.

Although the North Atlantic Right Whale is exclusively aquatic, it does need to breathe oxygen from the air like all other mammals. Between trips to the surface for a gulp of air, its dives last between six and eight minutes, but a Right Whale can dive for up to 60 minutes. It tends to remain in the upper 100 m to 150 m of water below the surface, since its prey is mostly found there, but can dive as deep as 200 m. Whales achieve this by slowing their heart rate, focusing their blood circulation in areas of the body where oxygen is most needed, and having specialized blood and muscles able to store more oxygen and to use it more efficiently.

Most Right Whales tend to stay in shallow, coastal waters, but we know very little about their other habitat requirements. Since Right Whales of different sexes and ages tend to stay together in often totally different areas, scientists think that they might have slightly different needs in habitat but we’re unsure exactly what these needs are. All North Atlantic Right Whales migrate to higher latitudes during spring and summer, but researchers still don’t know how they navigate. This migration is probably driven by prey distribution — the whales migrating to areas where food can be found.

Their natural ocean predators are sharks and Orcas, though they are only vulnerable when they’re young. It is thought that Right Whales remain in shallow waters, especially when giving birth, to reduce the chance of predation.

Range

|

| Distribution of the North Atlantic Right Whale |

For over 20 years, researchers didn’t know if all Right Whales on Earth were part of the same species, and if not, how they were related. In 2000, after studying the whales’ morphology (or physical features), the International Whaling Commission’s Scientific Committee recognized that the Eubalæna genus should be divided into three distinct species: E. glacialis for the North Atlantic, E. japonica for the North Pacific, and E. australis for all southern hemisphere Right Whales.

North Atlantic Right Whales inhabit the Atlantic Ocean, particularly between 20° and 60° latitude. Based on whaling records, we’ve been able to estimate that the North Atlantic Right Whale’s historical distribution included a large area of the eastern coastline of North America, from northern Florida to the waters of Atlantic Canada, and then east to southern Greenland, Iceland, and Norway, and south along the European coast to northwestern Africa. It is possible that the Right Whales of the eastern half of the Atlantic were of a different population, but this population is now considered Extirpated, or it is Extinct in the area. Since the 1920s, it has been very rarely seen out of North American waters.

Today, the North Atlantic Right Whale is found in the south from northern Florida up to New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and Québec in the north.

|

| Critical Habitat of the North Atlantic Right Whale in Canada |

Most adult females give birth in the warmer coastal waters of the southeastern U.S. during the winter months. Males and other females don’t tend to be in that area at all, and it is still unknown where they stay during the winter. A few adults and juveniles of both sexes have been spotted off New England states in the U.S. during the winter and spring, but scientists are still searching for the winter grounds of the remaining 70 per cent of the population. Right Whales start to migrate north in late winter and early spring, stopping to feed and socialize off the coast of Massachusetts. In June and July, and up until August and September, a very high proportion of the world’s North Atlantic Right Whales can be found in the feeding grounds in the Bay of Fundy and on the Scotian Shelf. But a shift to the Gaspé Peninsula, in Québec, and other areas of Atlantic Canada and the Gulf of St. Lawrence has been observed in the last few years both in the summer and fall. Starting in October, most Right Whales start to migrate south again, but it seems that some remain in Atlantic Canada as late as December.

Feeding

The North Atlantic Right Whale is from the order Cetacea, suborder Mysticeti. This means that it is a baleen whale which lacks teeth. Baleens are fringed plates made of keratin, like your fingernails. Two rows of these black or brown plates as long as 2.8 m hang from the Right Whale’s upper jaw, with 205 to 270 plates on each side of its mouth.

The North Atlantic Right Whale is from the order Cetacea, suborder Mysticeti. This means that it is a baleen whale which lacks teeth. Baleens are fringed plates made of keratin, like your fingernails. Two rows of these black or brown plates as long as 2.8 m hang from the Right Whale’s upper jaw, with 205 to 270 plates on each side of its mouth.

Its prey is zooplankton, or small, rice-sized crustaceans floating in the water, including copepods, euphausiids and cyprids. A Right Whale can eat as much as 1,100 kg of these tiny shrimp-like animals in one day. The Right Whale feeds by swimming slowly through water containing its prey, with its mouth opened. It takes huge gulps of the prey-filled seawater in its mouth, filters it through the baleens as it is pushed out again with its tongue when the mouth is closed. Some Right Whales have been spotted with mud from the ocean’s bottom on their heads. While we’re not certain why, it may be because the whales were feeding on prey located close to the bottom.

A Right Whale generally feeds from spring to fall, though, in certain areas, it may also feed in winter if prey is available. Its layer of blubber helps it store energy from the periods when it does feed, to be used during periods when it does not.

Breeding

Although it is thought that mating likely occurs in the winter habitat of the southeastern U.S., the whales’ mating system, and where and when exactly mating happens for this species, is not yet clear. We do know that Right Whales can sometimes form large groups, called surface active groups, in which many males compete for the attention of a female. But since this happens in their summer habitat, while Right Whales wouldn’t be mating, scientists are unsure why this happens. Even the actual length of the gestation, or pregnancy, is unknown, but it is thought to be of about a year long.

Although it is thought that mating likely occurs in the winter habitat of the southeastern U.S., the whales’ mating system, and where and when exactly mating happens for this species, is not yet clear. We do know that Right Whales can sometimes form large groups, called surface active groups, in which many males compete for the attention of a female. But since this happens in their summer habitat, while Right Whales wouldn’t be mating, scientists are unsure why this happens. Even the actual length of the gestation, or pregnancy, is unknown, but it is thought to be of about a year long.

A female Right Whale gives birth to its first calf at about 10 years old — the age it reaches sexual maturity. A Right Whale mother will give birth to one calf in the warmer waters off Georgia and northern Florida from December through March. A North Atlantic Right Whale calf is about 4.2 m in length at birth. A mature Right Whale will give birth roughly every two to six years, as a calf will be nursed by its mother for one to two years. After it is weaned and can feed by itself, it will remain close to its mother until sexual maturity. A female Right Whale can have offspring for about 28 years after reaching its sexual maturity.

Conservation

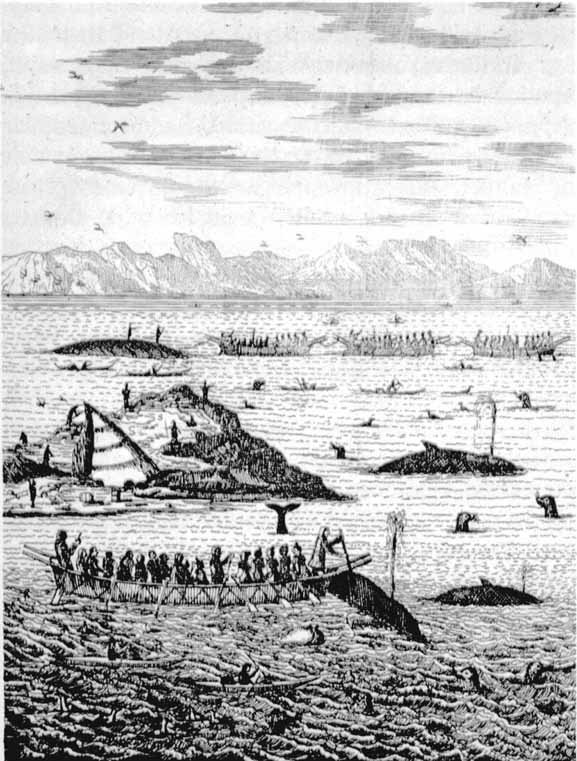

For thousands of years the North Atlantic Right Whale and other large whales had provided Indigenous peoples with skin, blubber, flesh and internal organs to eat, baleen and bones for buildings, furniture and tools, and oil for heat and light. Whales were so important to some peoples that a belief of the Mi’kmaq was that the whale is the master of life in the sea and an ally of Glooscap, the Creator.

For thousands of years the North Atlantic Right Whale and other large whales had provided Indigenous peoples with skin, blubber, flesh and internal organs to eat, baleen and bones for buildings, furniture and tools, and oil for heat and light. Whales were so important to some peoples that a belief of the Mi’kmaq was that the whale is the master of life in the sea and an ally of Glooscap, the Creator.

Starting in the 1500s, Basque, Breton and Norman seamen from France and Spain came across the Atlantic Ocean to the east xcoast of Canada in search of whales. Some records indicate they may have stopped whaling only after 80 years of heavy hunting had depleted the whale population in the region. Each whale had an enormous commercial value for their oil and baleen. The whales were used for food and fuel, but also to make horse whips, corsets, umbrellas, fishing rods, soap, cosmetics, shoe polish and paint. Sporadic hunting of North Atlantic Right Whales by Europeans, Americans and also Canadians continued through the 1700s, 1800s, and early 1900’s, until 1935, when a ban was put in place as the Right Whale was near extinction.

The total population in 2016 was estimated at 524 individuals. The species is considered as Endangered in Canada by the Species at Risk Act. Even though the species has not been hunted for 55 years, scientists have noticed that since 1990, the population is not recovering as quickly as they would expect. It has been increasing at a very low rate of only 2.4 per cent per year. This percentage is less than half of the growth of the other Right Whale species.

Since Right Whales mature somewhat slowly and they do not produce many offspring in their lifetime, the time between two consecutive generations in the lineages of a population, is long. They also have a low reproductive rate, meaning that not all mature females successfully reproduce. Another population-limiting factor might also be the low genetic diversity since the total number of individuals is so small. These factors make these whales more susceptible to threats, since the population can take decades to recover from an event causing a high number of deaths.

Threats to the Right Whale today include ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, disturbance by acoustic gear, habitat reduction or degradation (for example, by contaminants, and by variations in the food supply).

Governments and non-governmental organizations are working to help the North Atlantic Whale population recover. Shipping lanes have been moved in the Bay of Fundy to reduce ship strikes, and some fishermen in areas where right whales occur, adjust their fishing methods to reduce the chance of entangling whales. In July 2017, a large number of dead right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence prompted Fisheries and Oceans Canada to temporarily close the snow crab fishery for the year, and they issued a request to commercial shipping to reduce their speeds while passing through the areas for the remainder of the summer. Many research projects are also under way in order to fill the gaps in knowledge about the whale’s ecology and biology, for example the WHaLE project, a collaboration between the Canadian Wildlife Federation and 19 other organizations. These actions and discoveries will greatly help recovery efforts of this great whale.

Governments and non-governmental organizations are working to help the North Atlantic Whale population recover. Shipping lanes have been moved in the Bay of Fundy to reduce ship strikes, and some fishermen in areas where right whales occur, adjust their fishing methods to reduce the chance of entangling whales. In July 2017, a large number of dead right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence prompted Fisheries and Oceans Canada to temporarily close the snow crab fishery for the year, and they issued a request to commercial shipping to reduce their speeds while passing through the areas for the remainder of the summer. Many research projects are also under way in order to fill the gaps in knowledge about the whale’s ecology and biology, for example the WHaLE project, a collaboration between the Canadian Wildlife Federation and 19 other organizations. These actions and discoveries will greatly help recovery efforts of this great whale.

What we can do

If ever you spot a North Atlantic Right Whale, report it! Become the scientists’ “eyes on the water” and help them figure out where the whales are. Also, if you see a marine mammal in trouble, report it to your local marine mammal rescue organization with the help of CMARA.

Resources

CWF’s North Atlantic Right Whale Project Page

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, North Atlantic Right Whale

Species at Risk Registry, North Atlantic Right Whale

Whales Online, North Atlantic Right Whale

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2017. All rights reserved.

Text: Annie Langlois, MSc

Revision: Dr. Sean Brillant, PhD, Senior Conservation Biologist – Marine Programs, Canadian Wildlife Federation

CWF’s WHaLE Project

CWF’s WHaLE Project