Description

|

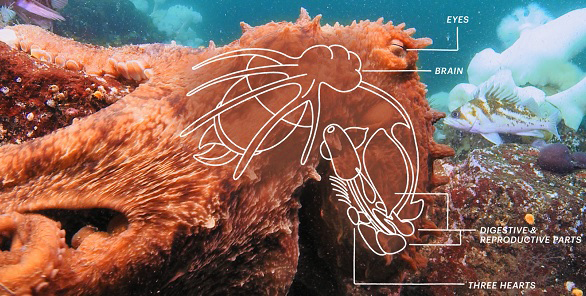

| Giant Pacific Octopus Underside |

The Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is a large cephalopod mollusk, which means it’s related to gastropods (snails and slugs) and bivalves (clams and oysters). Mollusks are invertebrates, meaning they have no bones. Insects are also invertebrates, but mollusks differ from insects in that they don’t have an exoskeleton. They are cold-blooded, like all invertebrates, and have blue, copper-based blood. The octopus is soft-bodied, but it has a very small shell made of two plates in its head and a powerful, parrot-like beak.

|

| Anatomy of the Giant Pacific Octopus’ head |

The Giant Pacific Octopus is the largest species of octopus in the world. Specimens have weighed as much as 272 kg and measured 9.6 m in radius (although they can stretch quite a bit), but most reach an average weight of only 60 kg. They’re normally reddish-brown in colour.

Signs and sounds

|

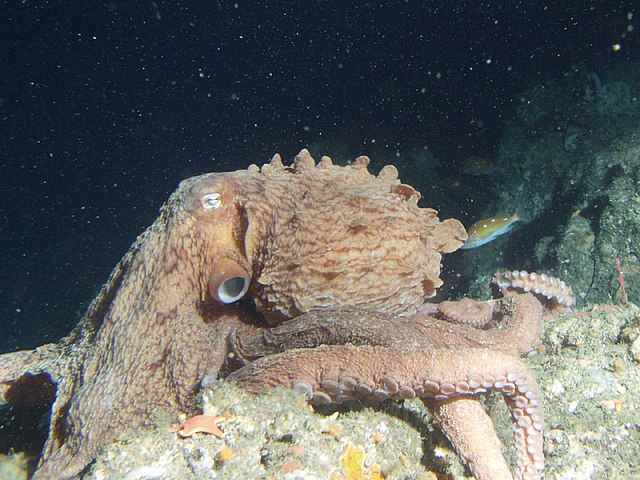

| Giant Pacific Octopus |

The Giant Pacific Octopus is considered a master of camouflage due to a complex system of pigment cells (chromatophores), muscles and nerves. It can change colour in one-tenth of a second to match the colour and texture of its surroundings. As they have no bones, octopuses also have an amazing ability to squeeze into tiny places, as long as those places are large enough for the octopus’s beak to pass through.

The octopus’s arms act as its legs and arms, helping it to crawl along the bottom of the ocean. When it needs to flee, it contracts its muscles, pumping water out of its body and propelling it to speeds of up to 40 km/h. To further confuse predators, it can expel a black ink-like substance through its siphon.

Octopuses have a great sense of taste that is up to 1,000 times more sensitive than that of humans. They also have the senses of smell and sight (although they might be colourblind), and they are very sensitive to touch.

|

| Giant Pacific Octopus opening bottle in captivity |

Octopuses are highly evolved and intelligent, especially when compared to their other mollusk relatives. Thanks to their highly developed brains, Giant Pacific Octopuses in laboratories and in captivity have learned to open jars, mimic other octopuses, interact with humans and solve mazes. They can also navigate by recognizing landmarks, and they are known to adapt objects to use as tools.

The Giant Pacific Octopus lives three to five years.

Habitat and Habits

|

| Kelp Forest |

Octopuses are solitary animals that live alone in dens, under boulders or in crevices. They can stay in their dens for weeks, leaving only to hunt food or mate. Ideally, the Giant Pacific Octopus’s habitat will have lots of hiding spots, like those provided by rocky areas and kelp forests. They can thrive in tidal pools and up to depths of 1,500 m in water temperatures as cold as 7 to 9.5 degrees Celsius.

|

| Tidal Pools |

Range

In Canada, octopuses are found in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. There are nine species of octopuses along the Pacific Coast.

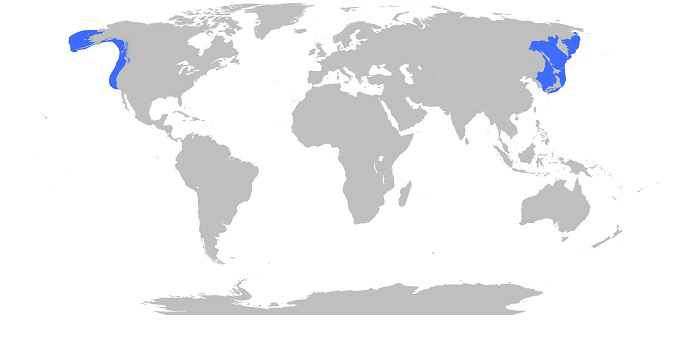

The Giant Pacific Octopus is found in coastal waters of the North Pacific Ocean, from Japan in the west, along Russia to the Gulf of Alaska and south to California.

|

| Distribution of the Northern Giant Pacific Octopus |

Feeding

|

| Giant Pacific Octopus eating a shark |

The Giant Pacific Octopus is a nocturnal carnivorous predator. It preys upon shrimp, crabs, scallop, abalone, cockles, snails, clams, fish and other octopuses. It has even been reported that a wild Giant Pacific Octopus attacked and drowned a seagull as its prey!

The octopus finds a likely spot for prey by sight, but hunts by touch, using stalking, chasing and camouflaging to ambush prey. Using its brain and sight, it can coordinate the use of all eight arms to attack its victim. The web between its arms can be expanded, parachute-like, to capture prey. They also dig in the sand to find clams.

When the hunt is over, the Giant Pacific Octopus returns to its den to eat. It chews with its sharp beak and radula (a tongue with teeth). Cephalopods also have paralytic and digestive toxins to help break down prey, but these toxins are not dangerous to humans. The uneaten remains of the prey are left at the entrance of the den.

The octopus, in turn, becomes food to marine mammals and Pacific Sleeper Sharks. Smaller octopuses can be prey to crabs and fish.

Breeding

|

| Female with her eggs |

Mating is one of the few instances when octopuses are not solitary. When it’s time to mate, a male octopus puts a 1m-long pencil shaped, transparent, gelatinous sack of sperm into one of the female’s large intake ports. The female stores this sperm for a while.

|

| Eggs |

A female will then find a lair to lay her eggs. This is often a large cave with a small opening, barely big enough for her to access it. The eggs, which are similar to grains of white rice, are laid on the ceiling of the cave, and are fertilized as they’re laid. Tens of thousands of eggs can be laid. The female will stay with the eggs until they hatch, not leaving them even to feed. She will live off her fat and proteins, brooding over her eggs, until she dies.

Octopus larvae are planktonic, and they float in the water until they are 50 mm in length.

|

| Larva |

Conservation

|

| Historical depiction of an encounter with an octopus |

Octopuses have been considered fomidable animals for millenia, featuring in people from all over the world’s artwork and stories. We now know much more about its intelligence and adaptability.

Luckily, the Giant Pacific Octopus is not a Species at Risk in Canada. Although the population numbers are unknown, it isn’t included on any endangered species lists. Indeed, it’s a relatively resilient species, as it has short reproduction times and regularly releases a large number of eggs. The octopus is not heavily fished recreationally. Even if it is commercially fished and eaten or used as bait, this is not done on a large enough scale to be a threat to the species.

But this doesn’t mean that the Giant Pacific Octopus couldn’t, at some point, be threatened by pollution or climate change, so we must still be vigilant and keep an eye on the species’ population.

What we can do

Please be mindful of the chemicals that you release in the water, especially in pluvial sewage systems. These products end up in our rivers and eventually in our oceans. Also try to reduce your plastic consumption. Plastics will disintegrate in landfills, and many of the resulting particles flow with rainwater into our watersheds. In short, keep in mind that what you throw out might reach the habitat of the octopus and other marine critters!

|

| Giant Pacific Octopus |

Resources

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/giantpacificoctopus-pieuvregeantepacifique-eng.html

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animal-guide/octopuses-and-kin/giant-pacific-octopus

http://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/what-we-do/resource-centre/featured-species/clams-snails-other-molluscs/northern-giant-pacific-octopus.html

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/g/giant-pacific-octopus/

https://www.vanaqua.org/education/aquafacts/octopuses-and-squids

http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/species-especes/shellfish-coquillages/octopus-pieuvre/index-eng.html

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/octopus-pieuvre-eng.html

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/inky-octopus-personality-behaviour-1.3537390

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/dec-8-2018-why-are-users-taking-fentanyl-making-stuff-with-moon-dust-an-app-to-detect-anemia-and-more-1.4935099/the-octopus-might-have-traded-its-shell-for-intelligence-1.4935115

https://web.archive.org/web/20121115121756/http://marine.alaskapacific.edu/octopus/factsheet.html

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/162958/958049#taxonomy

https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Enteroctopus_dofleini/

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/octopus

Writer: Annie Langlois

Reviewer: Jennifer Mather, Ph.D., University of Lethbridge