Description

The Redhead Aythya americana is a well-known and widely distributed North American diving duck. The adult male is a large, grey-backed, white-breasted duck with a reddish-chestnut head and black neck and chest. It resembles the larger male Canvasback. At close range, the head appears puffy, with an abrupt forehead and a short, broad bill, while the Canvasback’s bill is longer and slopes down from the forehead. The adult female is a large, brown-backed, white-breasted duck with a brown head, whitish chin, abrupt forehead, short, broad bill, and pearl-grey wing patches. Female Redheads, although larger, may be confused with female Ring-necked Ducks and scaups.

In autumn young Redheads resemble adult females, although their breast plumage is dull grey-brown, rather than white. During November and December, the young begin to develop the adult plumage, which has almost completely grown in by February.

The genus Aythya, to which the Redhead belongs, includes 12 species, all of which are well adapted to diving. The body is rounded and thick with large feet, legs set back on the body, and a broad bill. Body shapes vary from the big, long-necked, long-billed Canvasback to the short-billed scaup. The genus is represented in North America by the Canvasback, Redhead, Greater Scaup, Lesser Scaup, and Ring-necked Duck.

Signs and sounds

The voice of the courting adult male is unique. He makes a mewing sound like a cat to attract a potential mate.

Habitat and Habits

The Redhead is an open-water bird and during migration is sometimes found in huge congregations, called “rafts,” well out from shore in larger lakes and bays.

On the feeding grounds, Redheads move about in large flocks of irregular formation. They use areas of shallow water with dense growths of aquatic vegetation. Flocks rise from the water in apparent confusion as each bird patters along the surface for several metres before becoming airborne. For no apparent reason, large groups often fly up into the air together for a few metres and then resettle. Occasionally a flock flying over a large congregation on the water suddenly breaks up. Each bird drops out of the sky in a rapid zigzag fashion, as if with a broken wing, its flight path crossing that of other birds during the descent and its wing movements making a loud whirring sound. The periods of greatest activity are early morning and late afternoon.

Redheads roost in different, secure areas from where they feed. Like many diving ducks in the fall, they feed throughout the night, especially on moonlit nights with light winds. During migrations Redheads move in regular V-shaped flocks.

Adult males congregate on large lakes and bays in the northern prairie-southern boreal forest zone in June for the moult, or shedding old feathers, that starts at the beginning of August. The birds shed the flight feathers all at once and are flightless for almost four weeks.

Unique characteristics

Because of its short legs and webbed feet, the Redhead is a slow, relatively awkward creature on land. However, it is a powerful flier capable of speeds in excess of 80 km per hour.

Range

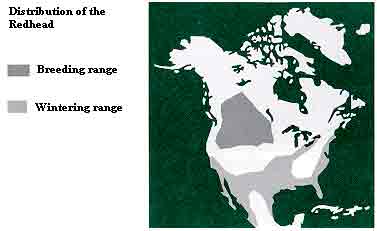

The Redhead’s principal breeding range is in the prairies of Canada and the United States. A particularly high concentration occurs near Great Salt Lake in Utah.

The Redhead’s principal breeding range is in the prairies of Canada and the United States. A particularly high concentration occurs near Great Salt Lake in Utah.

Redheads winter mainly in the Gulf of Mexico. Smaller numbers winter along the Pacific coasts of Mexico and the United States, and along the Atlantic coast from Chesapeake Bay to North Carolina. Several thousand Redheads winter on the Finger Lakes of upper New York State. Spring migration occurs early, with large numbers of birds arriving in southern Ontario by late March and in southern Manitoba by late April.

The southern migration is sometimes dramatic, with large numbers of Redheads and other diving ducks moving out of the prairies when suitable weather conditions occur. Large-scale movements are associated with northwest winds accompanying cold fronts. As the temperature drops in early October, the migration is well under way. Migrating flocks normally contain between 50 and 150 individuals.

By far the largest number of Redheads migrate almost due south from the breeding grounds to wintering areas in the Gulf areas of Texas and Mexico, although some move from the western prairies to the Pacific coast. From the eastern prairies, the migration is more complex. Whereas some flocks move southeast to the northern tributaries of the Mississippi River, following the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf coast, there is a large movement through the Lake of the Woods area in Ontario. Most of these birds then move to Lakes St. Clair and Erie, where they congregate in traditional areas with Canvasbacks and scaups, forming mixed flocks of 20 000 to 40 000 diving ducks. Furthermore, smaller numbers of Redheads move directly from the Lake of the Woods to the eastern end of Lake Ontario. In late October and early November, the birds that had congregated on the Great Lakes move through the Finger Lakes of New York State on their way to wintering areas along the Atlantic coast.

Feeding

Redheads feed by diving in water 1 to 4 m deep and sometimes feed on the surface in muddy shallow areas, as do dabbling ducks. Redheads consume a higher proportion of plant material than any other diving duck, with 90 percent of their diet including such plants as pond weeds, musk grass, sedges, grasses, wild celery, and duckweed.

Breeding

In late winter, courting parties of several males and one or two females may be seen. In one of several displays, the male throws his head back until the crown almost touches the tail feathers. He makes a mewing sound like a cat to attract a potential mate. A female sometimes approaches a male with her head erect, flicking her bill up and down and calling.

Pair formation occurs in late winter or in early spring during migration. The birds do not pair for life. After pair formation has occurred, the male follows the female back to the breeding grounds, generally near the place where she was reared. Redheads are late layers, and in the more northern breeding areas, incubation, or sitting on the eggs to warm them until they hatch, might not begin until mid-June, or even early July.

Redheads commonly breed on larger sloughs and marshes surrounded by cattails, bulrushes, and reeds, although nesting also occurs on smaller ponds. Nests are usually well hidden in emergent vegetation growing in shallow water, but have also been found on dry ground far from water. They are bulky structures made of reeds or cattail blades, deeply hollowed and lined with whitish down, or fine feathers. As incubation proceeds, the down layer thickens and eventually an insulating blanket is created with which the female covers the eggs before leaving the nest.

Redheads may incubate large clutches, or sets of eggs. The number varies from six to 27, but averages between 10 and 15 eggs. Larger clutches are the product of two or more females of this species and/or females of other species laying in the same nest. Redheads also lay eggs in the nests of other ducks, notably Canvasbacks. In drought years, many Redhead ducklings are raised by female Canvasbacks, when some Redhead hens lay eggs in Canvasback nests but do not make a nest of their own.

Eggs average 60 by 40 mm in size. The egg shell is exceptionally hard and is a glossy pale-olive buff or cream buff colour. The incubation period is about 24 days with only the female sitting on the nest. Incubating females do not leave the nest readily.

At about one day of age, the young are taken to suitable open water, where they obtain their own food, mostly floating plant material. At about seven or eight weeks of age, the young are fully feathered except for the wings, which are about half grown. They remain with the adult female until they can fly at about 70 days of age. Family units disperse in the early fall and young may or may not winter in the same area as their parents. Redheads can be long-lived. One bird that had been tracked by means of a numbered band attached to its leg was found to have attained the age of 16-1/2 years.

Conservation

The Redhead is one of our most important and sought-after game birds. All along its migration routes, market and sport hunters used to take large numbers of Redheads for food. Market hunting was prohibited in 1917, but the tradition of hunting Redheads with large sets of decoys, numbering 50 to 100 blocks or more, has persisted.

In the late 1960s, Redhead populations decreased greatly. In an attempt to allow the species to recover its former abundance, the federal governments of Canada and the United States protected Redheads through restrictive hunting regulations. Redheads increased again in the late 1970s and seem now to be in no danger.

Hunting regulations are based on the results of annual surveys conducted by the Canadian Wildlife Service and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in conjunction with provincial and state agencies. Each January, a North American census of wintering waterfowl populations is conducted to determine annual population trends. Breeding ground surveys are conducted in May to record population levels and waterfowl distribution. Hunting surveys provide important information on the rate at which a species is being harvested.

However, restrictive hunting regulations alone do not have a major bearing on Redhead populations. Waterfowl populations are limited today because wetland breeding, staging, and wintering areas are being destroyed by such activities as industrial development, urban projects, and agriculture. Periodic droughts also severely reduce the reproductive success of prairie waterfowl.

Federal, provincial, and state wildlife agencies in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, along with many nongovernment organizations, have developed the North American Waterfowl Management Plan to conserve and develop prime habitat throughout the continent for the Redhead and other waterfowl. However, many marshlands and sloughs continue to be destroyed, and much work remains to be done by all sectors to conserve wetland ecosystems.

Waterfowl management is playing a vital role in maintaining Redheads and many other aquatic species. Through efficient use of our land resources, provincial and federal policies seek to preserve an adequate supply of wetlands essential to meet continental waterfowl population goals. So long as people realize the need for, and actually conserve, our wetlands, it is certain that the Redhead will continue to be a valuable resource far into the future.

Resources

Online resources

Ducks Unlimited Canada, Redhead

Print resources

Bailey, R.O., and R.D. Titman. 1984. Habitat use and feeding ecology of post-breeding redheads. Journal of Wildlife Management 48:1144–1155.

Batt, B.D.J., et al. 1992. Ecology and management of breeding waterfowl. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Bellrose, F.C. 1981. The ducks, geese and swans of North America. Revised edition. Stackpole, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Dickson, K.M. 1989. Trends in sizes of breeding duck populations in western Canada, 1955–89. Progress Note No. 186. Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Palmer, R.S., editor. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 3. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1974, 1985, 1994. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/41-1994E

ISBN 0-662-21442-0

Text: Robert M. Alison

Revision: R.O. Bailey, 1994

Photo: Tony Beck