Description

The Canvasback Aythya valisineria is a wild duck that is found only in North America. The adult male, or drake, is a large white-bellied, grey-backed duck with a black chest, sloping forehead, and ruddy chestnut head and neck. The adult female is about the same size and has the same sloping forehead and long bill. Less colourful, she is more able to blend into her surroundings when on the nest or rearing her young. She is white-bellied with a pale brown back and reddish brown head, neck, and chest. Male and female Canvasbacks resemble Redheads and Ring-necked Ducks of the corresponding sex, but can be distinguished from them by their longer black bills and less abrupt foreheads.

In early autumn, the young of both sexes resemble adult females, although their breast plumage is more mottled and their back plumage is darker. During November, the young males begin to resemble the adult males, and by February the adult plumage of both sexes has almost completely grown in.

The genus Aythya to which the Canvasback belongs includes 12 species, five of which occur in North America. These are the Canvasback, Redhead, Greater Scaup, Lesser Scaup, and Ring-necked Duck. Generally, all Aythya species have rounded bodies with large feet, legs set back on the body, and a broad bill. They are all diving ducks.

Signs and sounds

During courting, the male utters a moaning, almost dove-like, ik-ik-cooo cry. The female answers with a low quacking cuk-cuk.

Habitat and Habits

During the nonbreeding period, Canvasbacks spend their time on open water in huge “rafts,” or floating flocks, which may extend for several kilometres in larger lakes and bays.

On their winter feeding grounds, they often form small compact flocks and fly about for pleasure, especially in the early morning and the late afternoon. Their wings create a loud whirring noise.

Wild ducks feed either by dabbling on the surface of the water, or by diving below the surface. Although Canvasbacks dabble at times, they are diving ducks because they usually dive for their food and because, like other divers, they have a special lobe on their hind toe that they use like a paddle in the water.

Unique characteristics

The Canvasback is a favourite of hunters, as it is delicious to eat if it has itself eaten certain foods. Canvasbacks take their scientific name Aythya valisineria from an aquatic plant, called wild celery Vallisneria americana, which is one of the foods that give this game bird an excellent flavour.

Among ducks, the Canvasback is one of the most powerful fliers, capable of speeds of 120 km per hour but it is an awkward bird on land due to its large size, short legs, and webbed feet. When taking off from the water, Canvasbacks patter along the surface for some distance before becoming airborne.

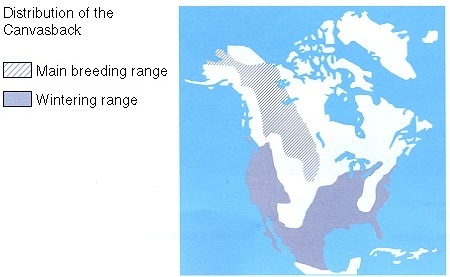

Range

The map shows the Canvasback’s principal breeding range in central Canada (mainly Alberta and Saskatchewan) and the northern United States. A lesser number breeds as far north as the Alaskan interior. Breeding pairs have been found as far east as Shoal Lake and Lake Manitoba; west to Grand Forks, British Columbia; south to Cimarron, New Mexico; and north to Fort Yukon, Alaska, and the Anderson River, in the Northwest Territories.

Canvasbacks winter mainly along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States and south to about 20°N. Typically, large numbers of these birds winter in the coastal regions of southern Maryland and Virginia.

The southern migration is well under way by mid-October. During migration, Canvasbacks usually fly high up in V-shaped flocks. Migrating flocks normally contain about 100 birds, but flocks often converge at traditional feeding areas along the migration route, resulting in assemblages of many thousand individuals.

Canvasbacks travel along three major migration corridors, or flyways. Those that nest in the central and eastern prairies migrate southeastwards to wintering areas along the Atlantic coast, primarily in Virginia and Maryland. This is the largest group, and these migrants head across Lake St. Clair and Lake Erie, either continuing south through the Finger Lakes of New York or flying eastwards to the eastern end of Lake Ontario before turning south. Small flocks belonging to this population migrate through the Montreal region, where they are relatively easy to observe. Another group of Canvasbacks moves from the central prairies to the northern tributaries of the Mississippi River, following the river valley to the Gulf of Mexico. The smallest group migrates from breeding grounds in western Alberta, interior British Columbia, and central Alaska to wintering grounds along the Pacific coast.

Adult males and young seem to congregate in large flocks during migration, whereas adult females appear to migrate along a broad front and are not common anywhere. The routes followed by migrating Canvasbacks have changed in the last century. Although few Canvasbacks were observed in Massachusetts or Maryland before 1895, the species is now common there. Large numbers of Canvasbacks now congregate on the navigation pools of the upper Mississippi River where few were previously observed. Sometimes, especially in the fall, individuals wander well beyond traditional migration routes: on rare occasions, Canvasbacks have been observed at Moosonee, Ontario, in eastern Quebec, in New Brunswick, in Nova Scotia, and in Bermuda.

The northern migration, from wintering to breeding ground, occurs in early spring. In most years, some migrants return to southern Ontario by late February and to southern Manitoba by mid-April.

Feeding

Canvasbacks usually feed by diving in water 2 to 9 m deep, but occasionally they dabble in shallow areas with surface-feeding ducks, especially American Wigeon. Their diet includes about 80 percent aquatic plants, primarily pond weeds, wild celery, duck potato, wild rice, banana water lily, and milfoils, or a species of flowering water plants. Canvasbacks also consume animal material, including insects, molluscs, or soft-bodied creatures with shells, such as snails, and various fish. Feeding generally occurs during the day, although Canvasbacks sometimes feed at night.

Breeding

By mid-February, courtship activities have begun. Commonly, several males court one or two females. A bright plumage helps a drake to attract a mate. A courting male throws his head back until the crown almost touches the tail feathers, then brings his head forward and utters a moaning, almost dove-like, ik-ik-cooo cry. The female answers with a low quacking cuk-cuk. At other times the amorous drake performs the kinked-neck display, in which the neck is stretched and bent forward momentarily.

Canvasbacks do not mate for life. Pairs form in late winter or during migration in early spring, and the female leads her mate to a nest site, usually near where she was reared. This species nests late, usually about the end of May in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

Canvasbacks commonly build their nests near open water in the shallows of large sloughs, or marshy areas, among cattails, bulrushes, and reeds. The nest is a large, bulky structure made of reeds and sedges and lined with drab brown down plucked from the female’s body. As incubation, or warming of the eggs until they hatch, proceeds, the layer of down thickens into an insulating blanket. The female uses this to cover the eggs when she leaves the nest.

As soon as the females have laid their seven to nine eggs, the males desert their mates and gather in large flocks on lakes and larger sloughs to moult, or shed old feathers. For two weeks, the males are unable to fly to escape predators due to loss of their flight feathers. Their plumage changes colour to look like that of the females, which is more effective camouflage, while they wait for new flight feathers to grow in.

The burden of incubating the eggs and rearing the brood falls on the females alone, and hens younger than five years old are frequently unsuccessful. The drab green or grayish olive eggs must be incubated for 24 to 28 days. A day or two after the eggs have hatched, the ducklings must be led safely to open water to find their own food, usually drifting plant material. The young do not develop feathers until about the fifth week, and are unable to fly until about 11 weeks.

In late summer, the females and young join the males. Family units split up during the early fall, and the young may or may not migrate with their parents.

The life span of Canvasbacks is poorly known, but individuals aged 10 and 19 years have been recorded.

Conservation

Hunters seek the Canvasback because it is so delicious. Before it became illegal to sell wild game, hundreds of Canvasbacks were taken daily using weapons, such as punt guns, and methods, such as night shooting, that have since been outlawed. Today, hunters use large flocks of 50 to 100 decoys to attract these curious trusting birds. This technique is especially effective early in the hunting season.

In the last 40 years, Canvasback populations have fluctuated from about 500 000 in the mid-1950s to about 200 000 in the early 1990s. In an attempt to ensure that populations remain healthy, the Canadian and American governments regulate hunting carefully. The Canadian Wildlife Service and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, in conjunction with provincial and state wildlife agencies, conduct surveys to determine total numbers of ducks and the annual hunting kill.

Restrictive hunting regulations are not enough to ensure healthy populations. Loss of habitat and periodic droughts on the breeding grounds cause declines in populations of this and other species. Loss of habitat results from farmers and developers draining wetlands and the use of vast expanses of former breeding range to grow crops. In addition, wintering range has been reduced in quality. For example, Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, no longer supports the wide range of plants that wintering Canvasbacks once fed upon.

Concern for the Canvasback and other wild ducks and geese that nest in prairie wetlands has prompted the various federal, provincial, and state wildlife agencies to cooperate in programs called “habitat joint ventures” under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, or NAWMP. Programs to enhance wetlands used by ducks and geese have been initiated in Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

Resources

Online resources

Audubon Field Guide, Canvasback

Print resources

Bellrose, F.C. 1981. Ducks, geese and swans of North America. Revised edition. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Delacour, J. 1959. The waterfowl of the world. Volume 3. Country Life Limited, London, U.K.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Hochbaum, A. 1944. The Canvasback on a prairie marsh. American Wildlife Institute, Washington.

Palmer, R.S. 1976. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 3. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1975, 1994. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/48-1994E

ISBN 0-662-22630-5

Text: R.M. Alison

Revision: J.S. Wendt, 1994

Photo: G.W. Beyersbergen