|

North American Lobster

North American Lobster Head North American Lobster Head

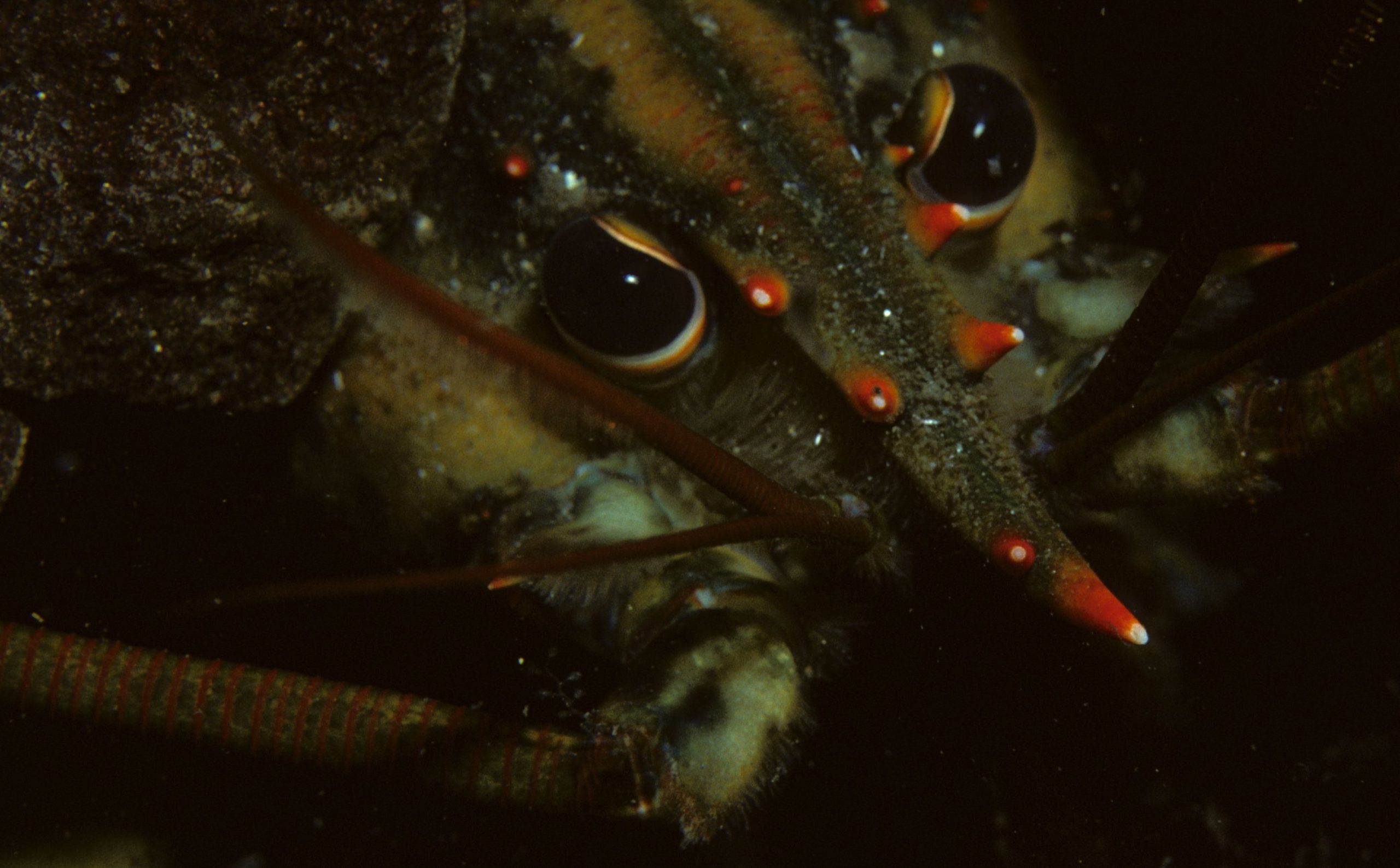

The American Lobster (Homarus americanus) is a marine invertebrate which inhabits our Atlantic coastal waters. As an invertebrate, it lacks bones, but it does have an external shell, or exoskeleton, making it an arthropod like spiders and insects. Its body is divided in two parts: the cephalothorax (its head and body) and its abdomen, or tail. On its head, the lobster has eyes that are very sensitive to movement and light, which help it to spot predators and prey, but are unable to see colours and clear images. It also has three pairs of antennae, a large one and two smaller ones, which are its main sensory organs and act a bit like our nose and fingers. These antennae are able to smell the water to locate prey and touch elements in the lobster’s environment so it can find its way. The lobster’s mouth is located just below its eyes. Around its mouth are small appendages called maxillipeds and mandibles which help direct food to the mouth and chew. Food is then brought to the first of the lobster’s two stomachs, which is just inside its mouth! The lobster’s respiratory system is made of gills, like fish, which are situated on each side of its cephalothorax.

North American Lobster Showing Its Different claws North American Lobster Showing Its Different claws

The lobster’s legs are also found on the cephalothorax. Lobsters have ten legs, making them decapod (ten-legged) crustaceans, a group to which shrimp and crabs also belong (other arthropods have a different number of legs, like spiders, which have eight, and insects, which have six). Four pairs of these legs are used mainly to walk and are called pereiopods. The remaining pair, at the front of the cephalothorax, are called chelipeds and each of those limbs ends with a claw. These claws help the lobster defend itself, but also capture and consume its prey. Each claw serves a different purpose: the bigger, blunter one is used for crushing, and the smaller one with sharper edges, for cutting. The claw used for crushing can be on the lobster’s right or left side, making it “right-handed” or “left-handed”. When a lobster’s limb, claw or antennae becomes damaged or lost, it is regrown when the lobster moults, a process called autotomy or regeneration. Hairs on the lobster’s legs and claws also act as sensory organs and are able to smell.

North American Lobster Missing A Claw

North American Lobster North American Lobster

The lobster’s tail is made of six parts and is articulated. You can find out if a lobster is male or female by looking under its tail. The first of the five pairs of swimmerets (or pleopods), small appendages which look like fins, differ between the sexes: the male’s are large and rigid, the female’s, much smaller and flexible. Other than to help during reproduction, the swimmerets help the lobster move. When a lobster needs to flee, it will swim backwards using its tail to propel itself. It can go at speeds of a few metres per second!

In order to grow, all arthropods have to shed their exoskeleton periodically. In the lobster’s case, when it outgrows its shell, it splits at the cephalothorax and the lobster backs out, having grown a new shell under the old one. In the beginning, this new shell is very soft, and it hardens over the following months. Because the moult makes it more susceptible to predators, a lobster will remain in its shelter throughout the process. During the first years of its life, a lobster may moult four or five times, but as it ages, moults become more spaced out. A lobster never stops growing throughout its lifetime, and since it can reach the impressive age of 60 years old, it can become quite large. According to the Guinness World Records, the largest lobster ever caught was in Nova Scotia, weighing 20.15 kilograms! Apart from growing throughout its life and being able to regrow limbs, researchers are studying another fascinating fact about the lobster: it doesn’t seem to slow down with age to become weaker or infertile. Lobsters will die from natural causes, but not necessarily of old age, and we actually don’t know how old they can live to be!

Blue North American Lobster Blue North American Lobster

Many people picture lobsters as red, but in fact that's only their colour after they've been cooked. North American lobsters can range from green and blue to red and orange depending on their habitat. Some are even white or of two separate coulours! Their blood is colourless and clear.

The American Lobster has only one close relative: the European Lobster (Homarus gammarus). Apart from living in different parts of the Atlantic Ocean, the European Lobster is typically blue-coloured, but hard to distinguish from the North American Lobster.

North American Lobster Habitat North American Lobster Habitat

The lobster can be found in waters ranging between –1.5 and 24 degrees Celsius, but prefer temperatures ranging from five to 18 degrees Celsius. An adult lobster generally lives in depths of less than 50 metres, although some have been found in waters as deep as 750 metres. During the summer, it tends to move to shallower and warmer waters, while in winter, most retreat to deeper waters for shelter against predation, low water temperatures, strong currents and storms. Younger lobsters stick to shallow waters year-round and usually remain hidden in shelters.

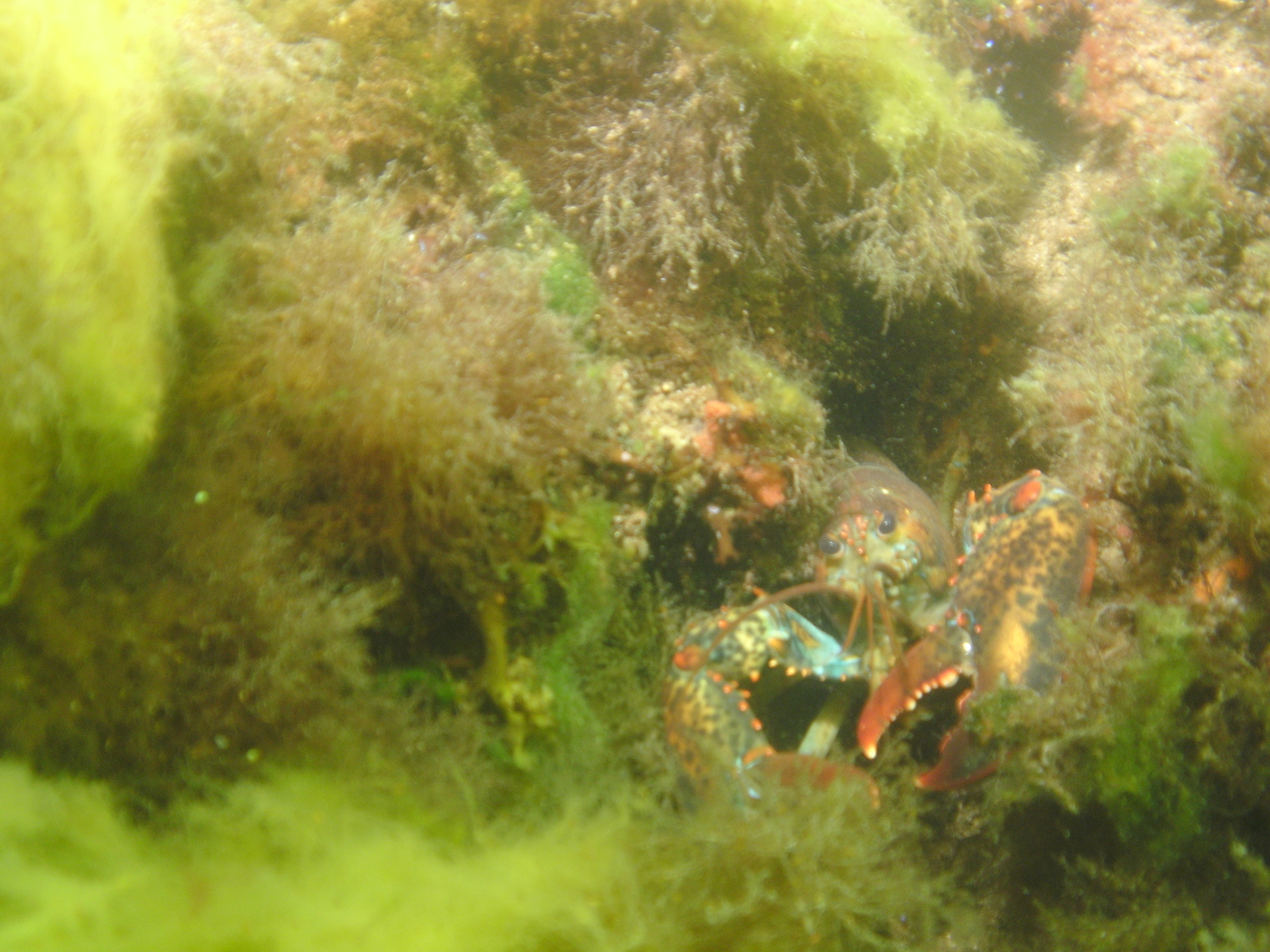

The lobster prefers areas with a rocky substrate covered with algae where it can find prey and many cracks and crevasses to hide in or it may dig a burrow under a rock. It could also dig a bowl-like hole to hide in the more marginal sand, gravel or mud habitat. Because the lobster is nocturnal, it spends most of the day in its shelter, always facing the exit so it can defend itself if a predator approaches.

North American Lobster In Its Habitat

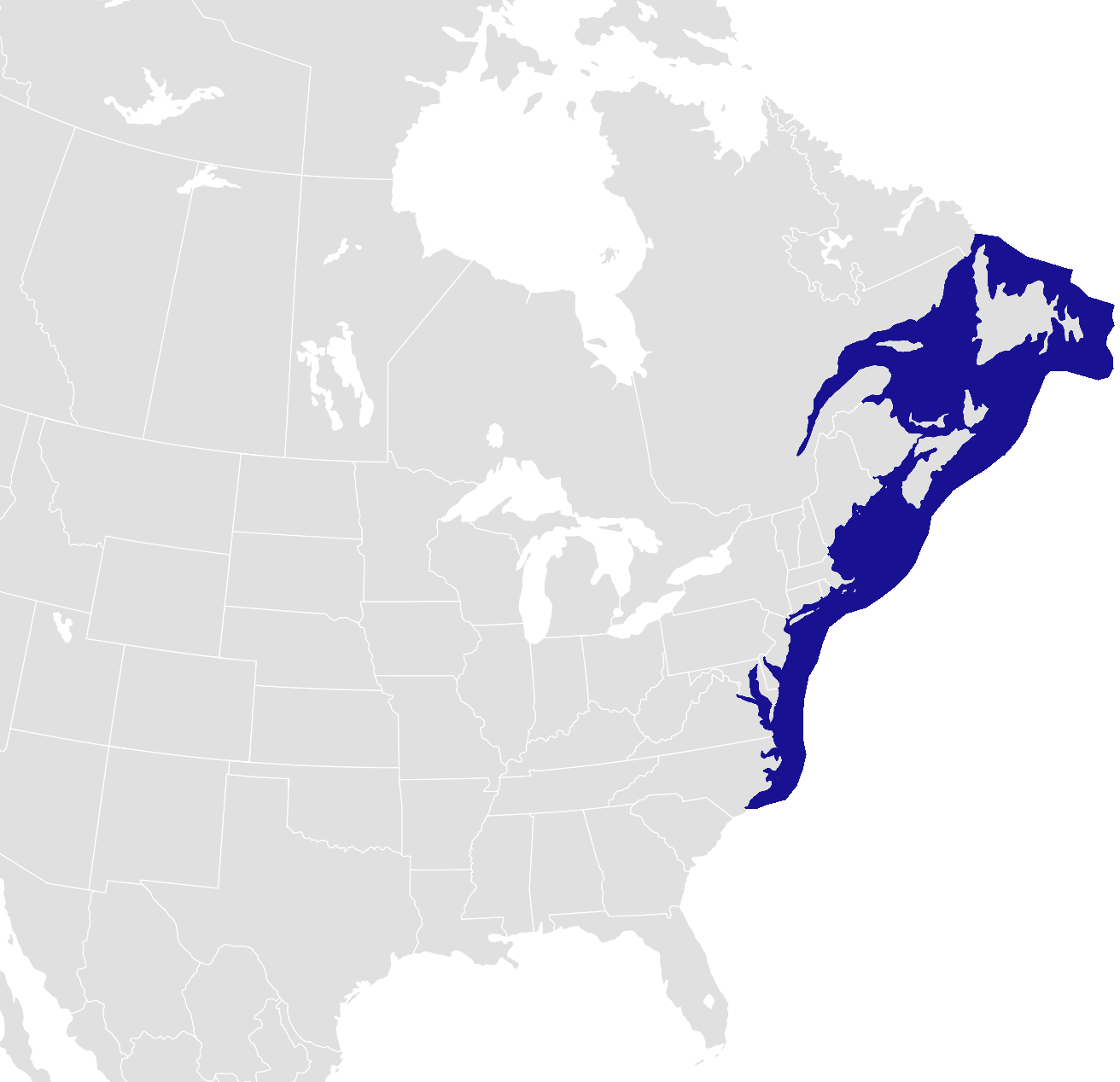

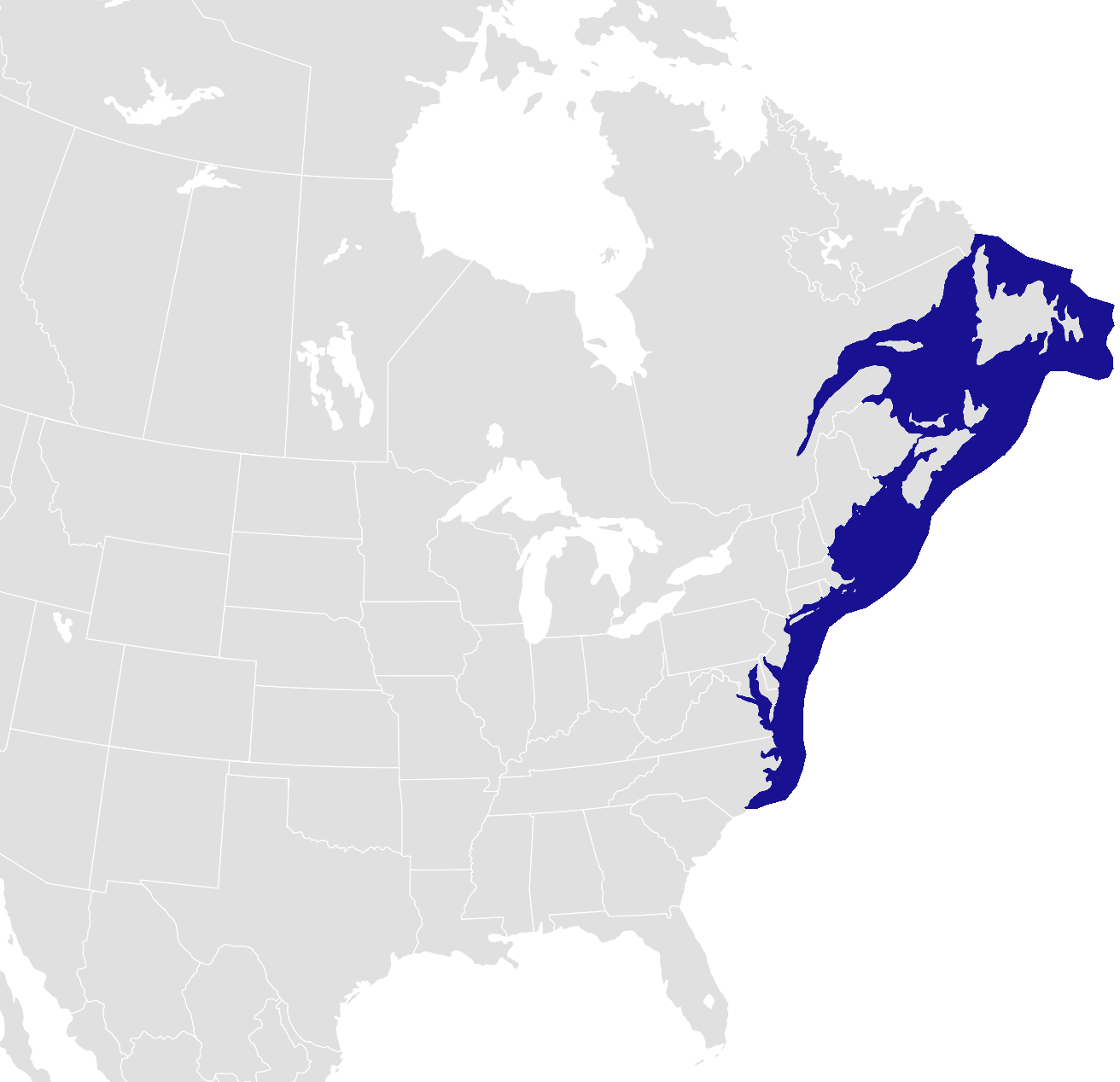

The American Lobster is found along the Northwestern Atlantic coast, from North Carolina in the United States to the Straight of Belle Isle, between Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada. Most lobsters live in the Gulf of Maine in the U.S., and in Canada close to Nova Scotia and in the southern part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

North American Lobster Distribution

North American Lobsters North American Lobsters

Lobster larvæ, which are free-floating, eat other free-floating organisms in the water-column called zoo- and phyto-plankton, or tiny animals and algæ. When they grow out of the larval stage and become bottom-dwellers, lobsters become active nocturnal hunters feeding on a wide variety of animals. The lobster’s prey includes crustaceans (mainly rock crab and other lobsters), shellfish (mussels, clams and scallops), marine worms, gastropods (sea snails and slugs), starfish, sea urchins and fish. They will also scavenge (they eat the remains of dead organisms). This helps recycling nutrients within the habitat, a bit like earthworms in forests’ soils!

In turn, adult lobsters are vulnerable to becoming prey to several fish species like sculpin, hake, cunner, cod, wolf fish and dog fish, even if larvæ are much more susceptible of becoming a meal.

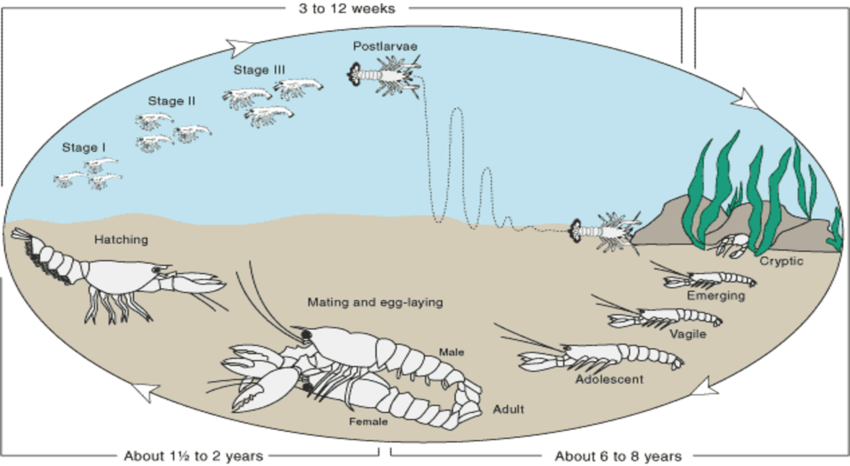

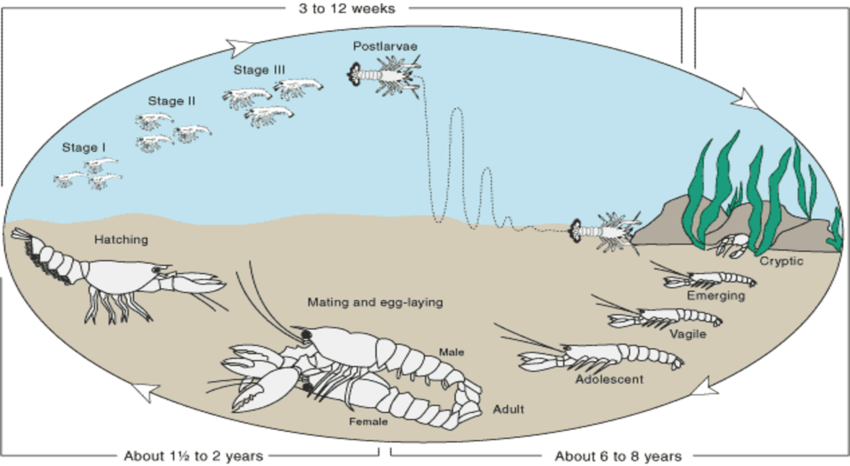

North American Lobster Life Cycle

Different stages of lobster larvae Different stages of lobster larvae

The lobster’s life cycle is both complex and fascinating. During the summer, females will attract males using pheromones (a “perfume” which is released in the water) in their shelters before moutling. The female will select a dominant male of similar or bigger size to mate. Immediately after the female has moulted, the male will then transfer his sperms into a special pouch located at the cephalothorax under the soft shell female, and will guard her against other potential mates (in order to protect his progenitors). She will only use the sperm to fertilize her eggs several months to a year afterwards as they are laid. The female keeps the fertilized eggs attached with a sticky substance under her tail for nine to twelve months. A female American Lobster could produce and carry between 2,000 and more than 200,000 eggs, depending on her size.

Female North American Lobster with eggs Female North American Lobster with eggs

In the summer, when water temperatures rise, female carrying eggs that are ready to hatch will release the larvæ by waving her tail. Larvæ initially swim close to the water’s surface and don’t resemble adults much. They are like small shrimps from seven to 11 milimetres long. After developing through three larval stages, a process that takes between two to five weeks, they become post-larvæ which look like tiny lobsters with claws called stage IV lobster.

As stage IV aged, it becomes more and more benthic and will settles on the seafloor. When it has found a good shelter, it hides to increase its survival. Then, as it becomes larger, it gets out further and further away from its shelter to feed. It becomes mature when its sexual organs are fully developed and it’s able to breed. Only about one to ten in 10,000 larvæ make it to adulthood.

Lobster Fishing Harbor Lobster Fishing Harbor

First Nations people living on the East Coast harvested lobsters long before Europeans arrived in North America, but it only became a commercial fishery in Canada in the 19th century. Prior to becoming a large-scale fishery, and even for some time afterwards in some areas, it was considered as food for underprivileged people or used as garden fertilizer since it was so easy to catch. Since then, the number of harvesters and boats have been increasing, and the lobster has become a highly valued commercial species.

Lobsters are caught with baited traps. A piece of fish is placed the “kitchen” of a wooden, plastic or metal trap in which a commercial-sized lobster can easily enter, but could not exit if it enters the “parlour” of the trap. These traps are left on the ocean floor for a minimum of 24 hours until they are hauled back on boats. Although raising lobsters in captivity through aquaculture is possible in theory, it has not been profitable.

In order to conserve lobster populations, some regulations, for example the release of caught egg-bearing females and the minimum size for capture, have been in place since the early 1870s. Within the last century, effort control measures, including limits on the number of fishing licenses and the number of traps per harvester, were introduced. Fisheries and Oceans Canada issues those restrictions and works in close collaboration with harvesters so that lobster populations remain viable in the long run. Groups of lobster harvesters are also a very important component of lobster research and conservation, leading projects on habitat conservation and fishing gear development. These groups are also active participants in educating the public about the lobster.

Lobster Trap Lobster Trap

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has also been gathering data to monitor the lobster population and to better manage the fishery. Research on the species is done both in the wild (for example, studies on behaviour, abundance, habitat, displacements and distribution) and in captivity (on the lobster’s physiology, metabolism, health and contaminant exposure). These projects are led by the Canadian government, universities and non-governmental agencies.

Other threats than the possibility of over-fishing could cause issues for the American Lobster in the long run. Climate change has already had an impact on lobster larvæ, and adult lobsters have been moving to deeper, off-shore waters in response to the warmer. Pollution, for example, the illegal use of pesticides by the salmon aquaculture industry, may also be a threat.

White North American Lobster White North American Lobster

A great first step to conserving the American Lobster is learning about it. Read about the lobster, and if you can, visit ecocentres that showcase the lobster when you visit Atlantic Canada! Once you’ve discovered this fascinating creature, tell people about it!

As for all other inhabitants of our coastal waters, you can help by keeping their habitat clean. Participate in a shoreline clean up. Be mindful of what you are flushing in our waterways, and some of it might end up in our oceans!

You can also help reduce the threat of climate change by making your home and appliances more energy efficient and choosing transportation options like public transport, cycling and walking instead of taking the car.

Most Canadians have only seen a lobster at a local fish store or as part of a fancy meal. But this crustacean is not only a tasty food, it’s first of all an essential species for coastal habitats and a part of our wildlife heritage. Let’s work together to conserve it!

|

|

Video & Sound

Video & Sound

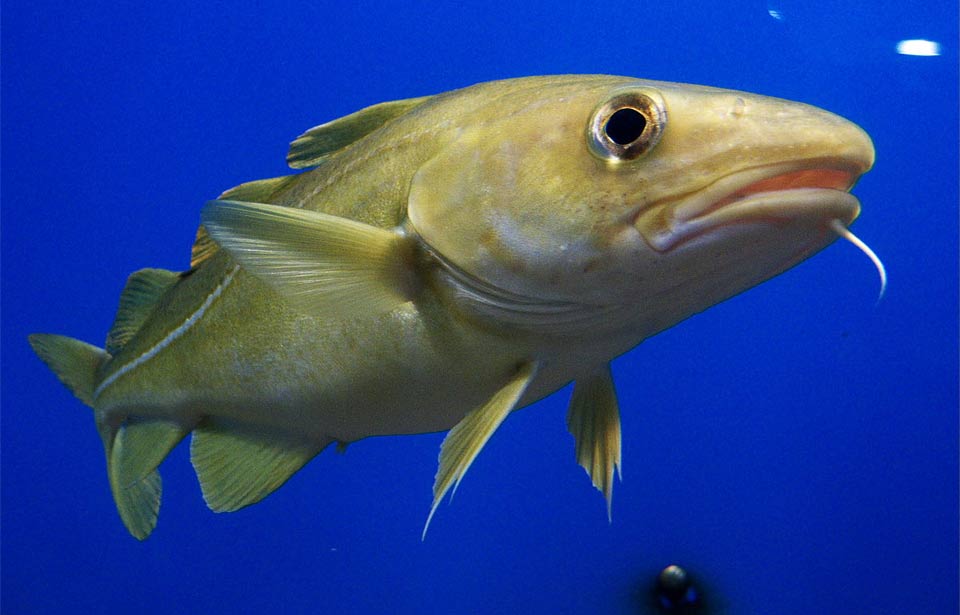

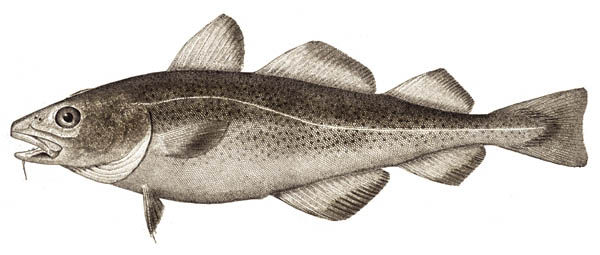

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

Ptarmigans are hardy members of the grouse family that spend most of their lives on the ground at or above the treeline. Three species are present in North America: the Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus, the White-tailed Ptarmigan Lagopus leucurus, and the Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus mutus.

Ptarmigans are hardy members of the grouse family that spend most of their lives on the ground at or above the treeline. Three species are present in North America: the Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus, the White-tailed Ptarmigan Lagopus leucurus, and the Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus mutus.