Description

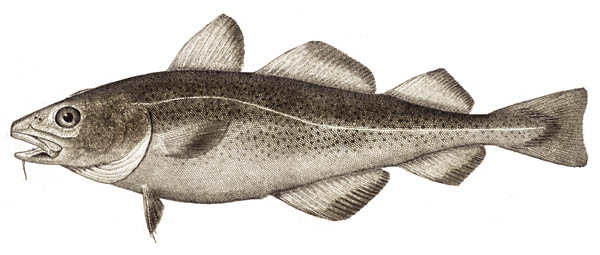

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

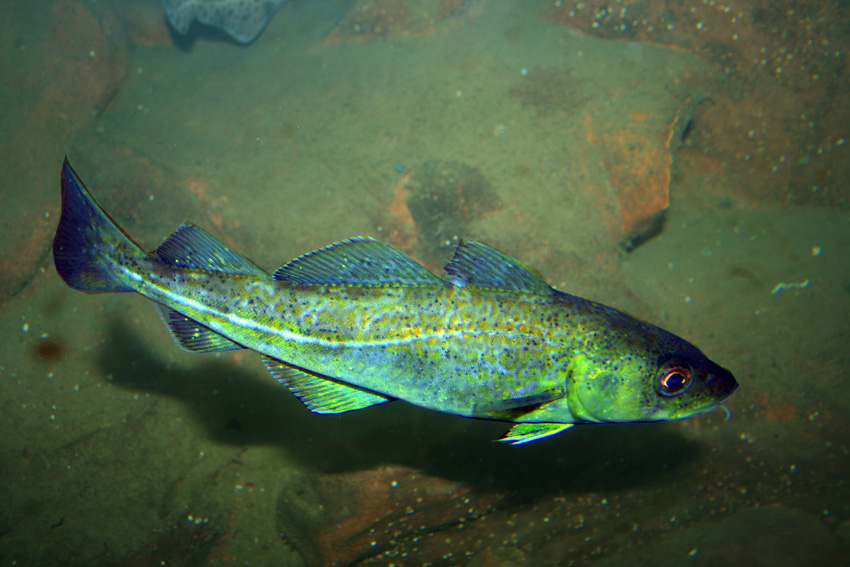

The Atlantic Cod shares some of its physical features with the two other species of its genus, or group of species, named Gadus. The Pacific Cod and Alaska Pollock also have three rounded dorsal fins and two anal fins. They also have small pelvic fins right under their gills, and barbels (or whiskers) on their chins. Both Pacific and Atlantic Cod have a white line on each side of their bodies from the gills to their tails, or pectoral fins. This line is actually a sensory organ that helps fish detect vibrations in the water.

The colour of an Atlantic Cod is often darker on its top than on its belly, which is silver, white or cream-coloured. Its exact colour varies between individuals and seems to depend on its habitat in order to camouflage, or blend in: when there’s lots of algae around, a cod can be reddish to greenish in colour, while a paler grey colour is more common closer to the sandy bottom of the ocean. In rocky areas, a cod may be a darker brown colour. Cod are often mottled, or have a lot of darker blotches or spots.

The Atlantic Cod may live as long as 25 years.

Habitat and Habits

A larval cod, before it matures into an adult, lives in the water column between the surface and the substrate at the bottom. It is said to be “pelagic.” As a cod grows older and matures, and although some remain in the open water their whole lives, it tends to move towards the bottom, living right above the substrate of the ocean floor. A fish living at the bottom of the water column is called “demersal.” Although an adult cod can live in a wide variety of habitats, it tends to be more common in areas of rocky, uneven substrate. Cod can be found from the shoreline down to the deeper waters of the edge of the continental shelf. This includes depths ranging from five metres all the way down to 600 m, and water temperatures from 0 to 20 °C.

Some populations, or stocks, of Atlantic Cod undergo seasonal migrations, for example moving from polar waters during the summer and fall to deeper, more southerly waters for the winter and spring. Others can move considerable distances in search of food. The Atlantic Cod is a shoaling species: it tends to move in large groups in order of size. Larger individuals typically lead the shoal, but the structure of the group may change when, for example, food is encountered.

Younger, smaller Atlantic Cod are preyed upon by many other fish species including Pollock and even larger cod. Adult cod are occasionally preyed upon by fish such as Spiny Dogfish and sharks, and marine mammals. Prior to its recent population decline, adult Atlantic Cod were considered top-tier (apex) predators in the northwest Atlantic.

Range

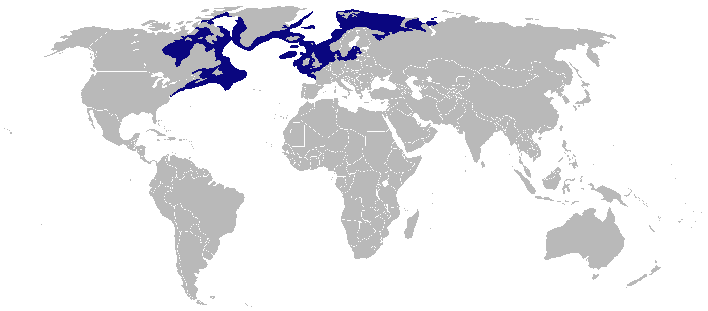

Atlantic Cod are found throughout the northern Atlantic Ocean, within a latitude of 80°N to 35° north. In the western Atlantic Ocean, these fish are found from Baffin Bay between Nunavut and Greenland in the north to North Carolina in the south. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, they live off the coast of Iceland and along the coasts of Europe from the Bay of Biscay between France and Spain in the south to the Barents Sea of Russia and Norway in the north. The largest cod stock in the world lives in the northeast Arctic, and is called the Arcto-Norwegian stock.

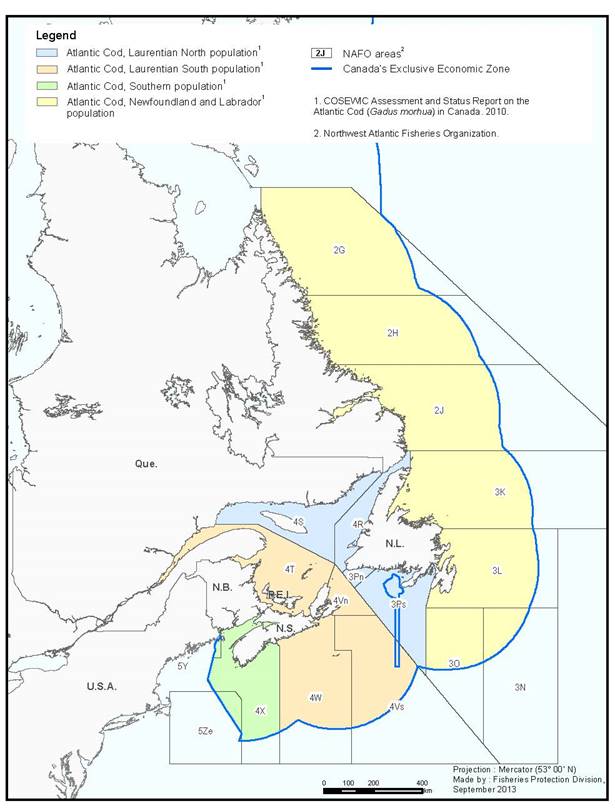

In Canada, Atlantic Cod are divided into 10 stocks, or populations. The map above shows the Eastern Canadian stocks. They are often physically different (in size and colour, for example) since they inhabit different geographical areas with different habitats. The stocks living in the low Canadian Arctic also tend to be migratory.

Feeding

Atlantic Cod are omnivorous, feeding at dawn or dusk on a wide variety of prey. Some even show cannibalistic behaviour!

Atlantic Cod are omnivorous, feeding at dawn or dusk on a wide variety of prey. Some even show cannibalistic behaviour!

Young cod feed mainly on small crustaceans such as euphausiids, copepods, amphipods, and other animals and larvae found floating in the water in the zooplankton. Adult cod feed on fish (capelin, herring, sand lance, flounder and turbot amongst others), crustaceans (crab, lobster and shrimp) and other invertebrates (including shellfish, brittle stars and comb jellies). In fact, a cod will eat almost anything including stones so that it can digest the anemones, hydroids, and other organisms growing on them.

Breeding

While female Atlantic Cod mature sexually at five to eight years of age, males generally mature at a slightly younger age and smaller size. When cod are mature, they spawn in a wide area of the continental shelf at the bottom of the ocean. Depending on where they live, cod can spawn from November (southwest Nova Scotia) to June (northeast Newfoundland).

If a female releases her eggs during mating, she will typically release from one to eleven million eggs. A larger female will typically lay more eggs than a smaller one. These eggs are one to two millimetres in diameter. Males are aggressive during spawning and create a dominance hierarchy over other males. When the eggs are released in the water column, subordinate or ‘satellite’ males compete amongst each other and with the dominant male to fertilize them. The fertilized eggs float in the water and rise to the surface, where they will hatch.

more eggs than a smaller one. These eggs are one to two millimetres in diameter. Males are aggressive during spawning and create a dominance hierarchy over other males. When the eggs are released in the water column, subordinate or ‘satellite’ males compete amongst each other and with the dominant male to fertilize them. The fertilized eggs float in the water and rise to the surface, where they will hatch.

A newly hatched larva is about five millimetres long, and will, at first, depend on a yolk sac filled with nutrients that is attached to its abdomen until it is fully absorbed. When the yolk sac is absorbed by the larva, it must start to look for food by itself in the water column. When it has grown to about four centimetres long, a young cod will move down to the substrate to forage.

The eggs, hatching larvae and young cod are very vulnerable to water currents and predatory fish: out of the several million eggs each female spawns, only about one egg of each million will survive to become a mature cod.

Conservation

The Atlantic Cod has been fished for thousands of years in North America by several Indigenous Peoples, including Inuit, Innu, Maliseet, Mi’kmaq and Beothuk. From 1,000 CE onwards, Europeans came to North American shores to fish for cod. The Norse were the first, followed, in the 1500s, by Spanish, Portuguese, French, Basque and English fishermen. These fishermen came across the Atlantic to fish only for the summer, going back to Europe in the fall. This seasonal fishery led to permanent settlements in what is now Canada, first by the French, then by the English.

By the 1800s, large fisheries were established along the east coast of Canada which harvested between 150,000 and 400,000 tonnes of cod annually. Northern Europeans preferred fresh cod and oil while southern Europeans and those from the West Indies preferred dried cod. The Atlantic Cod was an important fishery at the time, partly because the Catholic Church allowed its believers to eat fish on meatless religious holidays.

Until the 20th century, the tools used for cod fishery were relatively simple. But technological changes in the 1900s brought forth a new era into fisheries, enabling larger harvests. While the fishery remained stable until the 1950s at about 900,000 tons of Atlantic Cod caught, it increased to almost 2,000,000 tons in the 1960s with the use of large factory boats from Canada and abroad. Because of this unsustainable fishery, some offshore Atlantic Cod stocks collapsed in the 1970s. This dramatic decline in offshore Atlantic Cod stocks led to Canada extending control over coastal waters from 12 to 200 nautical miles to reduce foreign fishing, and to a five-year halt of the offshore cod fishery starting in 1977. But in 1985, the inshore Atlantic Cod stocks seemed to also be declining. In 1992, the Federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans declared a moratorium (or a stop) in the fishery of the Northern Cod stock, which had fallen to less one per cent of its original biomass. Other stocks that were also in trouble were also put under the moratorium in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The continued, unregulated and intense fishery of the Atlantic Cod had not only affected the number of cod, it also had an impact on the age and size at which cod reproduced (they became younger and smaller).

It might have also had an impact on its migration and on population structures (like the ratio of males and females or the number of fish of each age-group). This collapse also had a big impact on the fishing communities which had relied for decades on this fishery to provide employment.

In 2015, two reports on the Atlantic Cod offered hopeful but cautionary messages. In some areas, stocks seemed to be increasing in numbers, and their population structure (the age and sex ratios) seemed to be returning to normal. But with the additional threats of, for example, climate change, it is important not to draw conclusions too quickly or to generalize to all the stocks. More studies will be needed to be able to say that the Atlantic Cod is indeed recovering in our waters.

Currently, although the species is not legally considered At Risk in Canada by the federal government, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) has recommended that some stocks be considered Endangered. In the future, governments and fishermen will need to take action together to ensure that the Atlantic Cod stocks return to their former states and that this ecologically and historically important fish remains part of our natural heritage.

Resources

Search Aquatic Species at Risk

The History of the Cod Collapse

A Strategy for the Recovery and Management of Cod Stocks in Newfoundland and Labrador

Text by

Annie Langlois, M. Sc. Biology

Reviewed by

Jeffrey A. Hutchings, FRSC

Killam Memorial Chair in Fish, Fisheries and Oceans

Department of Biology

Dalhousie University

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2017. All rights reserved.