Description

The Osprey Pandion haliaetus is a large, powerful raptor, or bird of prey.

Adult birds have a dark brown back and white forehead, cheeks, neck, breast, and belly. A dark stripe extends from the base of the beak and across the eye to the back. The head and upper part of the breast are streaked brown, as is the underside of the wings and tail. In North America, the breast stripes are heavier on the female than on the male. The juveniles and adults look much alike; however, on the juveniles the brown feathers on the upper parts are tipped with white and the breast and head are more heavily striped. Ospreys acquire their adult plumage at about 18 months.

As is the case with most raptors, the female is larger than the male. She weighs on average 1.6 kg, compared with 1.4 kg for the male, and has an average wingspan of 163 cm, compared with 159 cm for the male. The adult Osprey measures anywhere from 53 to 65 cm long.

Anatomically, the Osprey resembles the eagle, but its narrow wings, when outspread, are markedly angled, and the structure of its feet and claws is so peculiar that it has been placed in a separate subfamily, the Pandioninae, of which it is the sole representative.

Unlike other raptors, the Osprey has four equal toes. The outer one is reversible, enabling the bird to seize its prey with two toes pointing forwards and two pointing backwards. A long, sharp, curved claw on each toe, and short, rigid spikes, known as spicules, on the sole of each foot, give the bird a firm grip on its slippery prey, which nearly always consists of fish that the bird catches alive, hence its nickname of fishing eagle or fish hawk.

Signs and sounds

For its size, the Osprey has a small voice, but if it is displaying or is feeling threatened, its cry will carry a fair distance. Usually, it gives out a whistling chook, chook, chook sound. The cry of the male, when frightened near the nest, is a shrill and frantic cheric, cheric, whereas the females give out a rapid pew, pew, pew sound.

Habitat and Habits

The Osprey is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world. It is found on ocean coasts and along the shorelines of large lakes and rivers on all continents and islands, except those in the polar and subpolar regions where water surfaces are frozen for most of the year, and a few very isolated islands in temperate and tropical zones.

Unique features

When an Osprey spots a fish from the air, it hovers at a height of 10 to 30 m until the fish is in a suitable position. Then, in a dramatic performance, the bird, huge yet wonderfully light, dives from the sky with its wings half closed and claws stretched forward, and disappears under the surface in a great spray of water, usually reappearing a few seconds later with a fish firmly clutched in its claws. Fortunately, the Osprey’s plumage is fine and dense, particularly on its feet, so that the bird does not get very wet. The Osprey carries its catch headfirst in flight, using both feet to hold all but the smallest fishes.

The Osprey was featured on the Canadian $10 bill for many years.

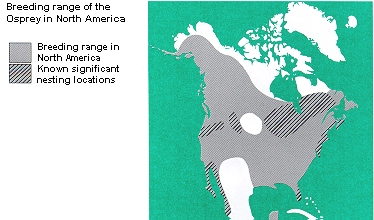

Range

Most Ospreys that nest in Canada migrate in spring from wintering sites in Latin America and the northern part of South America. However, migratory behaviour depends on age. The one-year-olds remain on the wintering grounds all summer. Of the two-year-old birds, 30 to 50 percent return in spring to the area where they were hatched, although they do not nest. Ospreys three years and older, which have reached sexual maturity, return to their hatching sites every spring to breed.

Most Ospreys that nest in Canada migrate in spring from wintering sites in Latin America and the northern part of South America. However, migratory behaviour depends on age. The one-year-olds remain on the wintering grounds all summer. Of the two-year-old birds, 30 to 50 percent return in spring to the area where they were hatched, although they do not nest. Ospreys three years and older, which have reached sexual maturity, return to their hatching sites every spring to breed.

Feeding

The Osprey searches especially for slow-swimming fish near the surface. In Canada, its favorite freshwater species are sucker, pike, and pickerel of moderate size. Occasionally, it catches fish weighing as much as 2 kg from aquaculture, or fish farm, ponds, to the consternation of the operators of the ponds and sometimes at the risk of its own life. In saltwater environments, it feeds mostly on plaice and tomcod, but also takes pollock, shad, and smelts.

Each day, the Osprey makes several patrols over the large expanses of water in its territory that offer the best fishing opportunities. When it sees a fish, it hovers at a height of 10 to 30 m until the fish is in a suitable position. The performance that follows is worth seeing: the bird, huge yet wonderfully light, dives from the sky with its wings half closed and claws stretched forward, and disappears under the surface in a great spray of water, usually reappearing a few seconds later with a fish firmly clutched in its claws. Fortunately, the Osprey’s plumage is fine and dense, particularly on its feet, so that the bird does not get very wet.

If the fish is large or difficult to control, the bird may have to make several attempts before it succeeds in rising out of the water. It has happened that an Osprey, after catching a fish that was too heavy, has been unable to loosen its grip and been dragged under water by its prey and drowned. Sometimes Osprey fish by skimming over the surface of the water and grabbing fish that are dead or dying.

The Osprey carries its catch headfirst in flight, using both feet to hold all but the smallest fishes. On occasion, a Bald Eagle will try to rob an Osprey by harassing it in flight until it drops its prey. Except during the nesting season, the Osprey perches near its fishing area to eat its catch, which it holds down with one foot and tears to pieces with its beak, devouring the head first. During nesting season, it brings the prey to the nest or to a perching place close by.

Breeding

In Canada, the Osprey most often nests in sturdy spruce or pine trees whose tops have broken off under the weight of snow or ice, providing a natural platform for the nest. In areas where large trees are lacking, perhaps as the result of a forest fire, the bird will sometimes nest on the ground, chiefly on large boulders in streams, atop rocks not accessible to land predators, and sometimes even on artificial structures such as power pylons, factory chimneys, hunters’ blinds, or the bare frames of abandoned wigwams. It uses artificial nesting platforms (erected with the encouragement of wildlife managers) in areas where natural nesting sites are lacking.

The Osprey’s nest is large and permanent, generally near water and at the top of a large tree. The tree may be alive or dead, but preferably should be strong enough to carry the weight of the nest, which consists of an immense mass of dried branches, interwoven with other materials, such as stakes, rope, strips of old cloth, plastic, and even caribou antlers.

To build its nest, the Osprey gathers branches from the ground or breaks them off trees by flying at them. Most construction takes place early in the nesting season but the Osprey may add to its home throughout the summer. In late summer, the bird spends a great deal of time repairing the nest for use in the following year. On average, the nests are 30 to 60 cm deep and 1 m in diameter, but some are more than 2.5 m across. Early in the season, a small hollow accommodates the eggs, but the nest grows flatter as the nesting season advances. Each year, the Osprey adds materials, and as a result, the weight of the nest sometimes causes it to slide down the trunk of the tree.

Generally, the Osprey defends its territory against other large birds such as eagles, owls, gulls, and the Great Blue Heron, which will not hesitate to take over its nest. The Osprey frequently takes the precaution of building more than one nest in its territory, especially if one year it does not manage to have young.

Some couples share the same nest year after year. At the start of the breeding season, when they are pairing or reaffirming their bond, they perform a spectacular display. The male repeatedly flies high into the air, hovers for a few seconds, dives, and reascends in a sweeping arc. Sometimes the female participates in a modified version of this display, making a show of pursuing the male. In another type of ritual display near the nest, the male flies laboriously, body arched and feet dangling below, often holding a fish or a branch in his claws.

According to estimates, nesting females lay an average of three buff-coloured eggs with dark brown speckles. The male takes little part in incubation, or warming the eggs until they hatch, and devotes most of his time to fishing. He is the sole provider for the family during the month of incubation and the subsequent month, when the growing chicks demand more than six fish per day. If food is abundant, two out of three chicks are usually able to fly after seven to nine weeks of constant parental care. Predation on eggs and young birds by crows, ravens, owls, gulls, and raccoons does not usually happen unless human activity has disturbed the parents.

According to the most recent estimates, about half of young Ospreys die in the first year; the mortality rate in subsequent years is between 16 and 19 percent. Available banding data (20 000 individuals have been banded in the last 60 years), indicates that Ospreys can live for 15 to 20 years; however, some individuals have lived much longer. The longevity record for the species is held by a banded bird that died, probably from a bullet, at age 35. Unfortunately, we don’t know whether this individual had bred every year up to its death. The greatest recorded number of breeding seasons for a single bird is 23.

Conservation

Like many other birds of prey that are high on the food chain, Ospreys throughout the world had breeding problems during the 1950s and 1960s. These problems arose mainly from the then widespread use of organochlorine pesticides, especially DDT. DDE, a substance produced when DDT decomposes, caused thinning of the shells of the eggs, which consequently tended to break under the weight of the female. Since the use of these products has been limited nearly everywhere, populations in areas where there is still suitable nesting habitat for the species have begun to recover.

Apparently it is the Osprey’s long life expectancy that enabled it to survive through those years of heavy pollution, despite low productivity. The bird’s amazing adaptability, which allows it to live near humans and to use artificial structures for nesting where there are no natural sites for its nests, reinforced by access to artificial reservoirs and ponds stocked with fish, has contributed to the recovery of the populations of Ospreys that were most strongly affected by pesticides.

Besides being a magnificent representative of North American wildlife, the Osprey acts as a biological indicator of environmental problems. And as long as people continue to act on the signals that this and other indicator species are sending out about the condition of the environment, populations of Ospreys and many other species will remain.

Resources

Online resources

Bird Studies Canada, Osprey

All About Birds, Osprey

Print resources

Bent, A.C. 1961. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Part I. Dover, New York.

Bird, D.M., editor. 1983. Biology and management of Bald Eagles and Ospreys. Harpell Press, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec.

Clark, W.S., and B.K. Wheeler. 1987. A field guide to the hawks of North America. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Newton, I. 1979. Population ecology of raptors. Buteo Books, Vermillion, South Dakota.

Palmer, R.S. 1988. Handbook of North American birds. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Poole, A.F. 1989. Ospreys: a natural and unnatural history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1993. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/66-1992E

ISBN 0-662-19415-2

Text: J.-L. DesGranges, S. Forbes, and J. Rodrigue

Photo: Wildlife Habitat Canada