Description

|

| Common Raven showing its hackles and large beak |

The Common Raven Corvus corax is one of the heaviest passerine birds and the largest of all the songbirds. It is easily recognizable because of its size (between 54 and 67 centimetres long, with a wingspan of 115 to 150 cm, and weighing between 0.69 and two kilograms) and its black plumage with purple or violet lustre. It has a ruff of feathers on the throat, which are called ‘hackles’, and a wide, robust bill. When in flight, it has a wedge-shaped tail, with longer feathers in the middle. While females may be a bit smaller, both sexes are very similar. The size of an adult raven may also vary according to its habitat, as subspecies from colder areas are often larger.

A raven may live up to 21 years in the wild, making it one of the species with the longest lifespan in all passerine birds.

|

| American Crow |

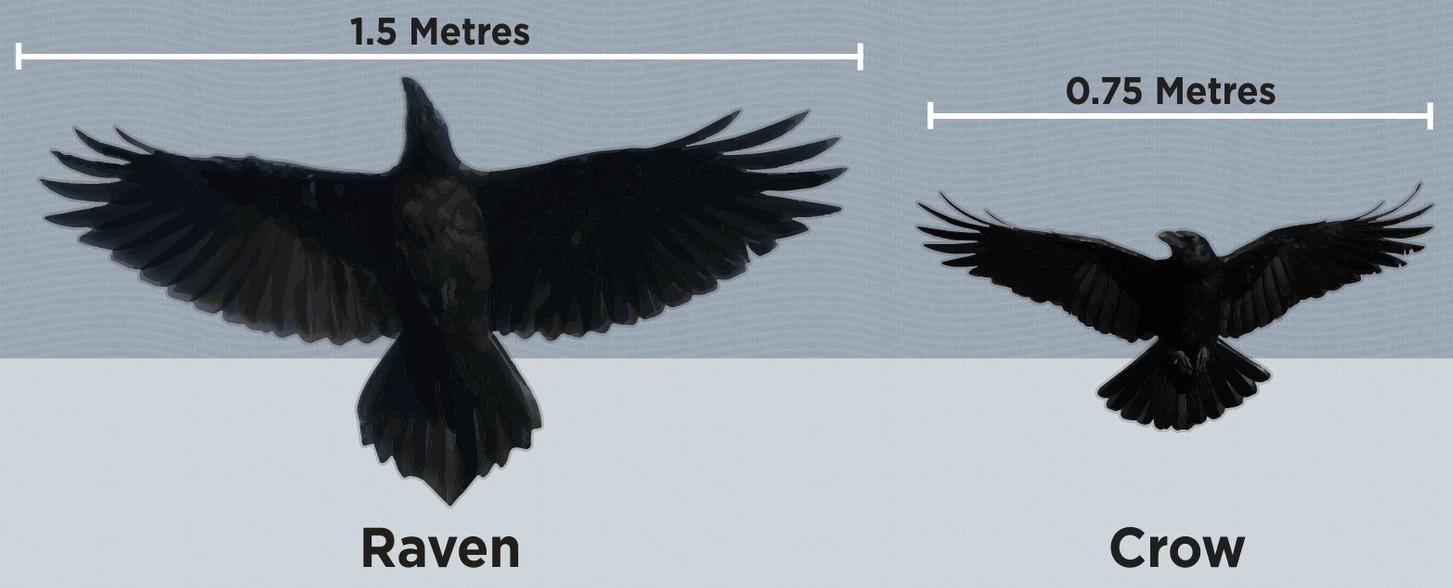

The Common Raven is often mistaken for an American Crow in southern Canada and the United States. Both birds are from the same genus (order of passerine birds, corvid family –like jays, magpies and nutcrackers, Corvus genus) and have a similar colouring. But the American Crow is smaller (with a wingspan of about 75 cm) and has a fan-shaped tail when in flight (with no longer feathers). It also has a narrower bill and lacks the raven’s hackles. Their cries are different: the raven produces a low croaking sound, while the crow has a higher pitched cawing cry. While adult ravens tend to live alone or in pairs, crows are more often observed in larger groups.

|

| Common Raven vs American Crow |

Signs and sounds

-Ravens have a tendency to soar and glide

-While their most frequent cry is a harsh, croaking call, Common Ravens are very vocal animals. They can produce a diverse suite of calls and sounds, all for different purposes. There are alarm calls, comfort sounds, hunting calls, and calls designed for advertising territories. Common Ravens are even able to mimic sounds heard in their habitat, but the reason they have this ability is not yet well understood.

|

| Common Raven Couple |

-Common Ravens also communicate with physical displays, using their beaks, wings and even hackles. Behaviours such as fighting or preening may be used amongst pairs, towards intruders or even to show submission to a dominant raven.

-Ravens are known for their intelligence. The brain-to-body weight ratios of corvid brains are among the largest in birds, equal to that of most great apes and cetaceans, and only slightly lower than a human. They seem capable of learning to apply solutions to newly encountered problems and will even use tools to get what they want. They are keen opportunists who watch and learn, often from above while soaring or perched, and are able to share their knowledge with other ravens.

-Common Raven groups show complex social dynamics, for example between dominant and submissive birds. But while younger, juvenile ravens live in groups, mature adults are highly territorial and most commonly occur alone or in pairs. Younger and older ravens may get together to forage in larger groups in areas where resources are concentrated.

-Ravens have been found seemingly playing with each other, even tricking other ravens or other animals.

-Adult Common Ravens are rarely preyed on, but fumbling nestlings may become prey to large hawks and eagles, other ravens, owls, and martens if their parents are not paying attention. The nests may also be attacked by predators, but ravens, which are attentive and protective parents, are usually successful at defending it.

Habitat and Habits

|

| Common Raven in the Rocky Mountains |

Common Ravens are some of the world’s most cosmopolitan birds! Found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, they’re habitat generalists. They are found in forests of all kinds, shrubland, rocky cliffs on coasts or mountains, the tundra, grasslands and even deserts. They tend to avoid large cities, but are common in smaller cities and towns.

Range

|

| Common Raven Distribution |

The Common Raven is observed across the Northern Hemisphere, and it is the most widely distributed of all corvids. The species is mostly sedentary and remains in the same area throughout the year, but northern populations may fly south for the winter.

This species is currently divided in eight subspecies, with small differences between them which are linked to adaptation to their habitat. In northern North America (including Canada and the northern United States) and Greenland, we can find the subspecies Corvus corax principalis, or Northern Raven. It lives throughout Canada except in the southern Prairies, where it was Extirpated, and in the heavily populated areas of southern Ontario.

Feeding

|

| Common Raven Eating a Prey |

Since the raven has adapted to living in such a wide variety of habitats, it is also able to feed on a broad range of food items. In fact, a raven will eat just about anything it can find! It is an opportunistic omnivore, mostly consuming animal matter but also plant matter if needed. It preys on adult and nestling birds, eggs, small mammals, sick and dying larger mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish and invertebrates. It also scavenges carcasses and may eat human food waste.

Ravens mostly find their food on the ground (except in the case of eggs and nestlings), and they are able to store some of it to eat at a later date.

Common Ravens tend to hunt for their food in mated pairs within a territory, but a group of juveniles may call loudly for adult ravens to join them to scavenge a large carcass. It also has been discovered that ravens can cooperate with other species in order to feed themselves: when a large live prey is spotted, ravens may call for local wolves to come and take it down. When the wolves are done with their meal, the ravens can, in turn, feast on the remaining carcass.

|

| Common Ravens, Magpies and Wolves |

Breeding

|

| Common Raven Nests |

A Common Raven reaches sexual maturity, or adulthood, at about three years of age. At this age, a raven will find a mate (it will remain with the same partner for life) with the help of elaborate displays. In courtship, males might use in-flight acrobatics to impress a female. When a pair is established, they will perch together, touch their bills and preen each other’s feathers.

The couple will then find a territory where it will spend most of its time, even outside of the breeding period. The territory’s size will vary according to the density if resources (like food and shelter) found in the area. For example, in vast expanses of barren land, territories will tend to be larger, and in lush forests, they will likely be smaller.

Both male and female ravens build a nest together, and tend to place it on large branches of trees, on cliffs or a man-made structure like a utility pole, a bridge, a radio tower or a building. The nest looks like a large, bulky basket made of sticks, and the interior is lined with softer materials such as roots, grasses and fur. The same nest is often used every year, the couple adding materials in order to maintain it.

|

| Common Raven Eggs in Nest |

Common Ravens breed once yearly. A single clutch of four to seven greenish eggs with olive or brown blotches will be laid from February (for southern ravens) to April (for Arctic ravens). The female incubates the eggs during the three week incubation period. While she can’t leave to forage, the male will find food and bring it to her at the nest.

When the nestlings hatch, they are fed and cared for by both their parents. They leave the nest about five to six weeks after hatching to form bands with other juvenile ravens.

|

| Common Raven Fledgelings |

Conservation

|

| Raven detail on Kwakiutl totem pole |

The raven is of high importance to Indigenous Peoples throughout Canada, appearing in myths, legends, art and traditions. It is particularly important to Aboriginal people of the British Columbia coast, where it symbolizes creation, knowledge and prestige. The raven is also a messenger, a trickster, a teacher, a healer and a guardian spirit. Inuit People also hold the raven in high esteem as the Creator of All Life, but it is a well-known clan totem for several other Indigenous Peoples.

While Indigenous Peoples generally perceived the raven as beneficial, it wasn’t the case for most the European people who came to North America. From the mid-1600s to the mid-1900s, ravens had been extirpated from some areas of northern and central Europe due to fears and superstitions. The same happened in the east and mid-west of North America before 1900, as people believed that ravens could harm their crops and livestock. In these areas, ravens were trapped, poisoned or shot, and the species is still largely absent from the southern Prairies in Canada partly because of these killing campaigns.

Even in areas where it was hunted out more than 100 years ago, the Common Raven is making a comeback. Perhaps because of the species’ adaptability, populations have been steadily increasing for the last 40 years in North America. But we still must be cautious, as it is unknown how the species will react to possible threats such as climate change and habitat destruction.

And it’s important to keep the raven around. Not only is the Common Raven a fascinating species with strong ties to Canada’s Indigenous Peoples, it is an important inhabitant of our ecosystems, helping nutrient cycling by consuming carrion and controlling prey populations. Getting to know the raven and dispelling its dark reputation is a great first step!

Resources

|

| Common Raven |

https://corvidresearch.blog/category/raven-behavior/

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/dinner-guests-how-wolves-and-ravens-coexist-at-kills/

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/raven-symbolism/

https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/totems-to-turquoise/native-american-cosmology/raven-the-trickster/

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2018. All rights reserved.

Written by Annie Langlois, B.Sc. Biology